5 May 2019, Palais Garner, Paris

This short and sparse triple bill, consisting of two works from the team of Sol León and Paul Lightfoot, along with a single work from Dutch master Hans van Manen, showed more than anything the extreme physicality of the dancers of the Paris Opera Ballet. The men in particular displayed a muscularity that was not, for the most part, concealed by decorative costumes and all the dancers showed a strength of technique that was powerful and engaging.

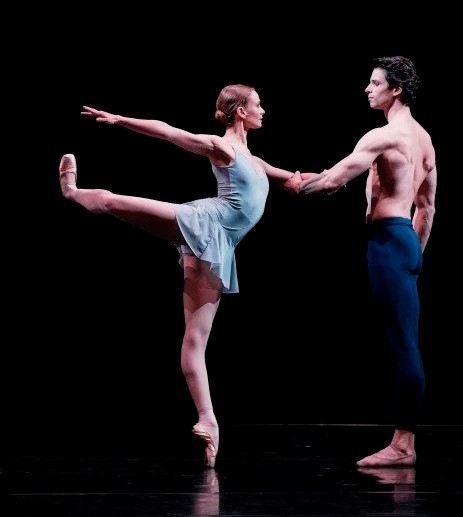

The works of León and Lightfoot are not, however, the most comfortable to watch. It is not that ‘comfort’ is necessarily an important aspect of dance, but both of their works on this program, Sleight of hand and Speak for yourself, had features that seemed to me to be like stunts and gimmicks. Hans van Manen, on the other hand, had a different approach with his Trois gnossiennes, danced to Erik Satie’s piano score of the same name. Van Manen relied on the manipulation of his chosen movement vocabulary, basically that of classical ballet, to create effects. To that vocabulary he added upturned feet, tilted torsos that rarely, however, lost the straight line of the spine, expansive lifts, bodies pulled off centre, and other manipulative features that gave us a beautifully sculpted work. It was finely danced by Léonore Baulac and Florian Magnenet and for me it was the highlight of the program, despite being only eight minutes in length. The Satie score was played live by Elena Bonnay.

Léonore Baulac and Florian Magnenet in Trois gnossiennes. Paris Opera Ballet. © 2019 Agathe Poupeney/OnP

Of the other two works Speak for yourself was the more interesting in my mind. There was a kind of narrative or concrete idea behind the work, which related (the program notes tell me) to masculinity and femininity. These ideas were symbolised by the presence of smoke and water. Smoke represented speed and rapid action (masculinity) while water represented gentleness and calm (femininity). There was a contrast between the fast movement of the early part when one dancer had some kind of device attached to his body that pushed smoke into the surrounding space, and the slower movement of the final section when water poured down onto the stage as a kind of backdrop. But, quite honestly, I think this kind of representation of male and female differences is outmoded and I enjoyed the work mostly for the way in which the choreographers played with the human body in their movement vocabulary. Bodies curled in on themselves and stretched out beyond what one might expect, for example.

As for Sleight of hand, it was hard to comprehend what was behind it. As the work opens, two dancers, one male, one female, stand on obelisks (although we cannot see those structures as they are covered by the extension of the costumes). They tower above the rest of the cast. Who are they? They scarcely move at first but then do so only from the waist upwards. They gesticulate wildly. Other dancers come on stage and perform until at the end one dancer is left alone as the curtain falls. I love being asked to create my own interpretation of a work, but this one, despite its inherent theatricality, left me without anything to hang on to.

I have so much admiration for the dancers of the Paris Opera Ballet, but this program was not the most admirable one I have seen.

Michelle Potter, 8 May 2019

Featured image: Silvia Saint-Martin and Simon Le Borgne in Speak for yourself. Paris Opera Ballet. © 2019 Agathe Poupeney/OnP