Daily Deaths

5 December 2020, Futuna Chapel, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The practice of dance notation has always intrigued me. The notion of recording in symbols a choreography, of studying a dance form, style or technique, of documenting a dance tradition or of analysing human movement for medical and therapeutic purpose, seems intrinsically interesting. Using a camera to video a dance does not begin to capture or analyse the depth, detail and intricacy of movement as a notation can. Different systems of dance notation exist, and it is interesting to compare the analytic concepts on which they are based. The foresight of Doris Humphrey and Jose Limon in commissioning notations of their entire choreographic repertoires into kinetography Laban (Laban notation) ensures that their numerous classic works can continue to be performed long after their lifetime.

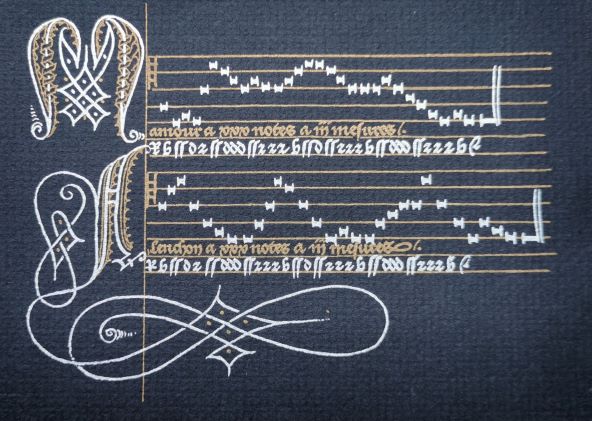

The very earliest examples of notated dances in European history, date from 14th century France, Spain and Italy. They are the mediaeval basses danses, scribed into exquisite miniature calligraphy, jewel-like in silver and gold on a black background. The music tenor, the guidelines to the composition and the initials of the names of the steps are all notated. Musicians today can play from these notes ( they are breves on a stave, without bar lines ), dancers can learn the style and memorise the steps—thus an eight hundred year old dance can be breathed back into life. I always say to students that doing a basse danse is a bit like dancing the rosary—a string of steps with variations, in a sequence that creates a meditative quality of abstract thought. That is not a bad description of a music performance I just witnessed in Wellington last weekend—so, not a dance as such, but a meditative witnessing of tragic statistics of Covid mortalities. You could have set a basse danse to the music.

Futuna Chapel in Karori proved an ideal venue for this highly unusual event. John Scott’s architecture is itself a work of art, and the stained-glass panels by sculptor Jim Allen threw a wash of colour, backlit by sunshine, into the space. Those attending might have felt they were at a vigil for a global phenomenon in history, rather than merely an audience at a conventional concert. There were no doubt challenges for some who are new to this world of alternative music-making, but the strong and sustained final applause signalled that many had had a uniquely memorable experience.

Composer Daniel Beban made an hour long work from the sobering statistics of 8 different countries’ Covid mortality rates these past months, layering and morphing these into graphic scores for 18 musicians in a range of paired wind and string instruments.

Long slow breaths from each performer in the opening section developed into breathings through the instruments without yet sounding tones. Then notes were blown for the length of a sustained slow breath, or bowed for the duration of a slow single stroke. Some instruments merged into each other’s sounds, some became more dominant, evoking images of individuals struggling to breathe, to survive, against whatever odds. It seemed like an abstracted report on experience from the front line, at times dreamlike, though sometimes involving nightmares.

The composition played out as a serious witnessing of untold numbers who have suffered, survived, or not survived this vicious pandemic. I felt grateful to be able to contemplate that sad wider picture without the cacophony of reports of a few braying politicians in denial of science, recipients of hugely expensive treatments for their own care yet with no sense of community or empathy—contrasting with the reality of pleas for help from the front-line, and epidemiologists who need us to listen and to act responsibly and humanely.

The fact that the composer is my son-in-law and one of the musicians my daughter is what some might perceive as a conflict of interest within this review, but for me that only reinforced the truth that for every name on the lists of the dead, there’s a family left to hold on to memory. This work seemed like a basse danse, a rosary of consolation for them.

Jennifer Shennan, 9 December 2020

Featured image: Page from the manuscript Basse danses de Marguerite d’Autriche, XV century, Flemish School. Bibliothèque royale de Belgique. Brussels.