In mid-October 2014, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London opened an exhibition, Russian avant-garde theatre: war, revolution & design, in its Theatre and Performance Galleries. It consisted of around 150 works, most of which came from a twenty year period between 1913 and 1933, that is just before the Revolution of 1917 until the beginnings of Social Realism in the 1930s. The majority of items, largely works on paper, came from the Bakhrushin State Theatre Museum in Moscow with smaller amounts of material from the St Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music, the Victoria & Albert Museum and from private collections.

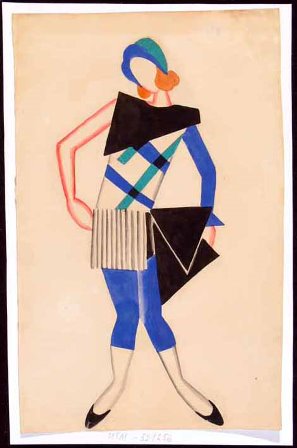

The designs were mostly in spectacular condition, especially in terms of colour which seemed scarcely to have dimmed over the century or so since the designs were painted. With the prominence that has been given to the designers who worked with Diaghilev over approximately the same period, many of them Russian, this exhibition was an exceptional opportunity to see another side of Russian design.

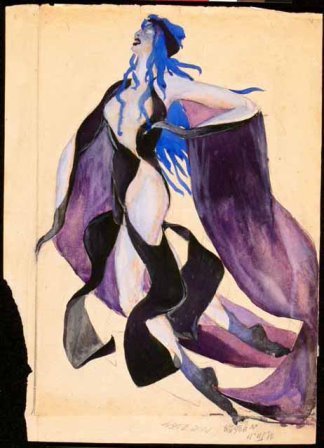

Many of the theatrical works represented had never been realised in performance. Satanic Ballet designed by Alexandra Exter, for example, is thought to have been prepared for the Moscow Chamber Ballet and was meant to be a series of improvisations without thematic content, but never made it to the stage. Other productions were of course realised but what was interesting was that the designs often showed movement despite the fact that they came from a period when the art being produced in Russia was dominated by constructivism. Some designs have a real fluidity to them, others remain within the constructivist mode but still show some potential for body movement.

A handsome book was produced for the exhibition and of particular interest as far as dance is concerned is an essay by Nicoletta Misler entitled ‘Precarious Bodies: Performing Constructivism’. Misler writes of Satanic Ballet:

Naked bodies—in keeping with Goleizvosky’s [the choreographer] interest in the culture of nudist performance—were to have leapt and twisted along diagonal ladders leaning against a void as if to confirm Exter’s conviction that ‘free movement is the fundamental element of the theatrical act’. (p. 55)

In her essay Misler also examines, briefly, the role of the Choreological Laboratory, part of the Russian State Academy of Artistic Sciences established in Moscow in 1921, and the research into the theory of movement that was carried out there. Her discussion of the various experiments carried out and the outcomes in terms of theatrical expression seem to me to be well worth following up.

Unfortunately the book doesn’t have an index but it is full of illustrations of a remarkable collection of designs and a selection of essays that are mind-expanding.

Russian avant-garde theatre: war, revolution and design (London: Nick Hern Books, 2014)

ISBN 978 I 84842 I 453 I

Michelle Potter, 26 November 2014

Looks terrific! Oh to be in London…. Do you know of the book “Russian and Soviet Theatre – Tradition and the Avant-Garde”? Thames & Hudson 1988 and then 2000 Konstantin Rudnitsky Some terrific designs for sets and costumes, mostly for theatre but many are very “balletic”….

No, I don’t know that particular book Judy. But amongst my collection I do have a book, edited by Nancy van Norman Baer (a wonderful dance and theatre scholar), called Theatre in Revolution: Russian Avant-Garde Stage Design, 1913–1935. It accompanied an exhibition at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in 1991 (which I didn’t see). It covers most of the same issues, is devoted to material from the Bakhrushin Museum, and also has an article (more detailed that the V & A essay) by Misler on the Choreological Laboratory.

But that old expression ‘there’s nothing like being there’ holds true. To see the designs in real life, in their incredibly beautiful colours, was such an amazing experience. I have wondered about them coming to Australia.