- Sydney Dance Company in 2023

2023 marks Rafael Bonachela’s fifteenth year as artistic director of Sydney Dance Company and he has announced that he will continue in the role for another five years. The 2023 season will open with a triple bill called Ascent co-commissioned by the Canberra Theatre Centre. As such it will have its opening performances in Canberra followed by a season at the Sydney Opera House as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the House.

Ascent will feature a brand-new work by Bonachela, the return of Forever and Ever by Antony Hamilton, first shown in 2018, and a world premiere by Spanish choreographer Marina Mascarell. Of the program Bonachela says, ‘After the challenges of the past few years, I am so pleased to again be commissioning an international artist whose works have garnered critical acclaim around the world, alongside showcasing the work of a brilliant Australian choreographer.’

And I am so pleased that Canberra will be the city hosting the premiere of Ascent. Sydney Dance Company has been touring to Canberra pretty much annually (last year, 2021, is the only exception that stands out in my mind) since the 1970s. It is great to see this initiative, for which we must acknowledge the Canberra Theatre Trust for its co-commission.

Further information on the 2023 season is available on the Sydney Dance Company website. It includes information on the company’s regional tour, and its season of Up Close, a new venture to bring the company and audiences closer together and which will include a new work from Bonachela called Somos (meaning ‘we are’ in Spanish).

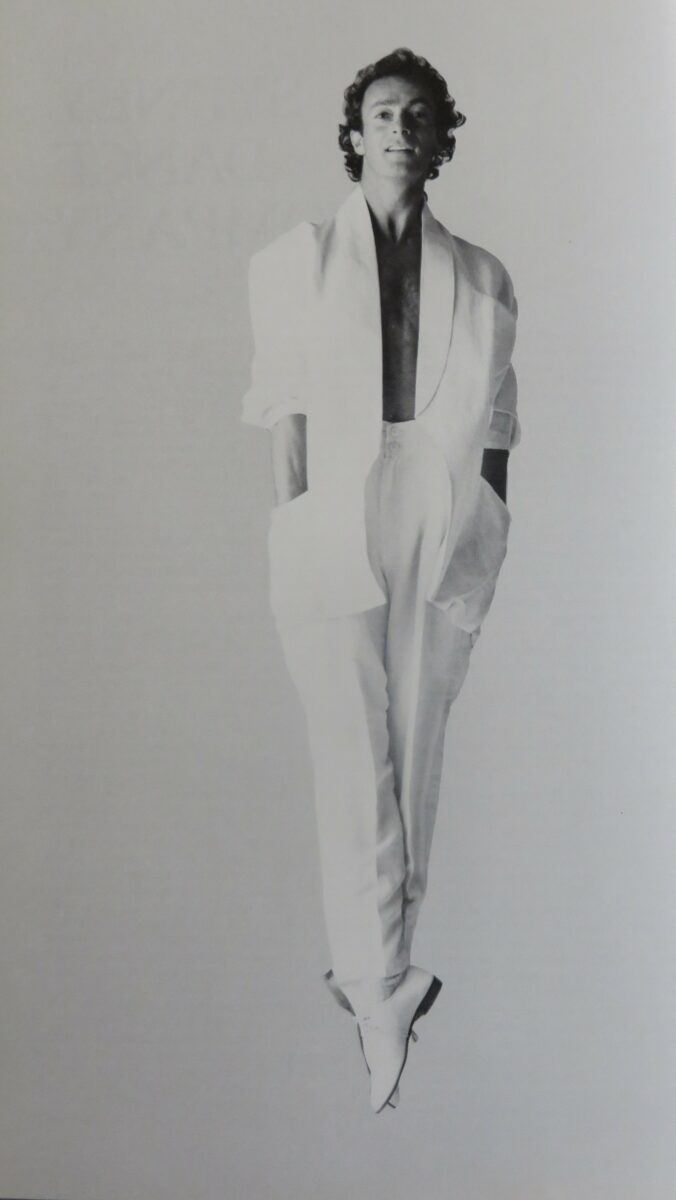

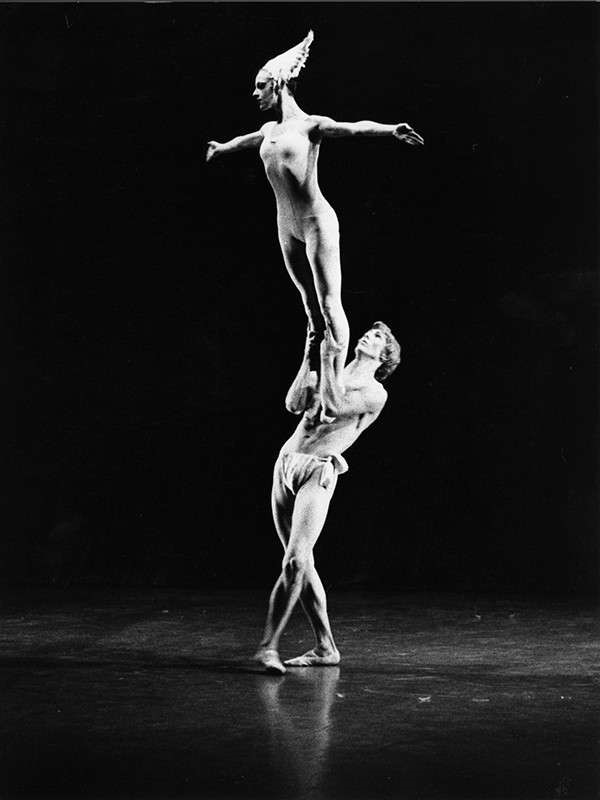

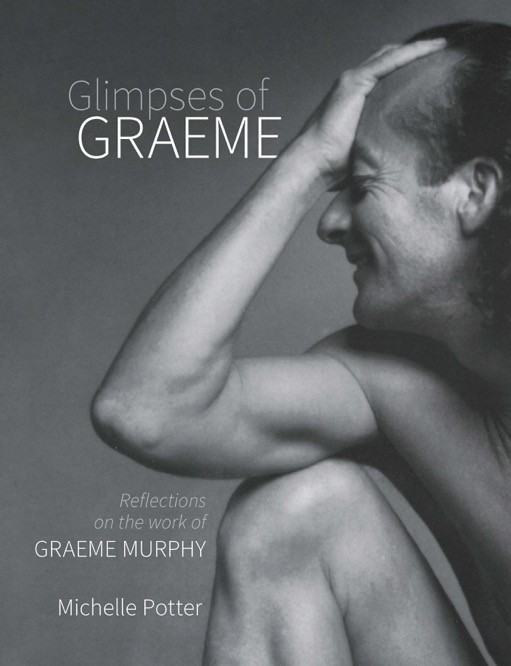

- Launch of Glimpses of Graeme

Hobart, more specifically the Battery Point Community Hall, was the site for the launch of my latest book, Glimpses of Graeme. Reflections on the work of Graeme Murphy. The event was beautifully hosted by the Hobart Bookshop and it was a full house for the conversation between Graeme and me, which was moderated by Lucinda Sharp. Also featured were two short excerpts from works created for MADE by Murphy and danced by Sue Pickard and Laura Della-Pasqua, the official launch by Shirley Gibson from MADE, and a book signing.

In the image below, taken at the end of the event, see (l-r) Lucinda Sharp, dancer Susan Pickard, Michelle Potter, Graeme Murphy, Bronwyn Chalke (owner of Hobart Bookshop), dancer Laura Della-Pasqua (at rear), Shirley Gibson from MADE who did the official launch, and Janet Vernon.

Copies of Glimpses of Graeme are available from FortySouth online book store at this link.

- Eileen Kramer turns 108

Early in November Eileen Kramer, once a dancer with Gertrud Bodenwieser, celebrated her 108th birthday. These days she works closely with film maker Sue Healey and a group of close friends in Sydney, where she currently lives.

See this tag for posts about Kramer on this site. My favourite is a link to a film made by Healey in 2017, which won an Australian Dance Award. Happy returns to Eileen Kramer.

- News from James Batchelor

James Batchelor’s Shortcuts to familiar places premiered in Berlin in October and was toured to Bangkok in November. Batchelor has recently shared two comments on the work, including one from Australian dance artist Alice Heyward. Heyward’s essay is beautifully and thoughtfully written and constructed and so worth reading. Here is the link.

Michelle Potter, 30 November 2022

Featured image: Publicity shot for Sydney Dance Company’s 2023 season. Photo: © David Boon