- BOLD Bites

The BOLD Festival started as a biennial event in 2017 but it suffered in terms of being biennial as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It will, however, be back in a mini form in March 2024. BOLD24 will be a ‘Bite Size’ initiative and will feature a series of events celebrating International Women’s Day 2024. It will anticipate the next major BOLD festival in 2025. BOLD Bites will, as is the focus of all BOLD activities, honour intercultural, inclusive and intergenerational dance.

The program will take place over three days, from 8 to 10 March, in various venues in Canberra. Further information shortly on the BOLD website. Stay tuned. UPDATE: Here is a link to the schedule.

I will be involved in three conversation sessions:

BOLD critique with author Emma Batchelor on writing about dance in reviews, articles and other formats. Our conversation will be followed by an open Q & A session.

BOLD Moves with Elizabeth Cameron Dalman focusing on the foundations of Mirramu on Lake Weereewa, and on the inspiration Dalman finds in nature. It will be a prequel to the premiere screening of a new film, Lake Song, choreographed by Dalman, directed by Sue Healey and featuring Canberra’s company of older dancers, the GOLDS.

BOLD Diva with Morag Deyes, former director of Dance Base in Scotland. This conversation will focus on the rich tapestry of Deyes’ career as the leader of Dance Base and as the founder of PRIME, Scotland’s premier dance company of elders.

- New dancers for Sydney Dance Company

Sydney Dance Company has announced that five new dancers will join the company for its 2024 season—Timmy Blakenship, Ngaere Jenkins, Ryan Pearson, Anika Boet and Tayla Gartner. It was more than interesting to read a brief biography of each of these new dancers. Two have strong New Zealand connections (Jenkins and Boet); Blakenship was born, raised and trained in dance in the United States; and Pearson and Gartner are Australian with Pearson having a strong First Nations background and a memorable early career with Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Sydney Dance Company has always been a company of dancers with diverse backgrounds but with the new additions in 2024 that diversity is being strengthened. And from a personal point of view, after watching Ryan Pearson perform so magnificently with Bangarra Dance Theatre, I really look forward to watching him work with Sydney Dance Company. Below are brief biographies of the five new artists (taken from the Sydney Dance Company media release):

American dancer Timmy Blakenship was born on the Lands of the Arapaho Nation/Colorado, and completed his early training in contemporary dance and choreography at Artistic Fusion in Thornton, Colorado and Dance Town in Miami, Florida. He continued his training at the prestigious University of Southern California’s Glorya Kaufman School of Dance on scholarship, graduating with a BFA in 2023 where he performed works by William Forsythe, Jiří Kylián, Merce Cunningham and Yin Yue.

Ryan Pearson was born and raised in Biripi Country/Taree, New South Wales and is of Biripi and Worimi descent on his mother’s side and Minang, Goreng and Balardung on his father’s side. Ryan began his dance training at NAISDA at age 16, after taking part in the NSW Public Schools’ Aboriginal Dance Company, facilitated by Bangarra’s Youth Program Team in 2012. Ryan joined Bangarra Dance Theatre in 2017 as part of the Russell Page Graduate Program and was nominated in the 2020 Australian Dance Awards for Most Outstanding Performance by a Male Dancer for his performance in Jiri Kylian’s Stamping Ground.

Originally from Wadawurrung Country/Geelong in Victoria, Tayla Gartner commenced full-time training at the Patrick Studios Australia Academy program in 2018 before undertaking the Sydney Dance Company’s Pre-Professional Year in 2022, where she performed works by choreographers including Melanie Lane, Stephanie Lake, Jenni Large, Tobiah Booth-Remmers and Rafael Bonachela. In 2022, Tayla worked with and performed repertoire by Ohad Naharin and was a finalist in the Brisbane International Contemporary Dance Prix.

Born in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Ngaere Jenkins is of Te Arawa and Ngāti Kahungunu descent. Ngaere trained at the New Zealand School of Dance, graduating in 2018. Throughout her studies, she worked with influential mentors including James O’Hara, Victoria (Tor) Colombus, Taiaroa Royal and Tanemahuta Gray. Ngaere represented the school as a guest artist in Tahiti at the Académie de Danse Annie FAYN fifth International Dance Festival and Singapore Ballet Academy’s 60th Anniversary Gala. From 2019 Ngaere was a dancer with The New Zealand Dance Company and was the recipient of the Bill Sheat Dance Award.

Raised in Christchurch, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Anika Boet is of South African and Dutch descent. Moving to Sydney in 2020, Anika completed two years of full-time training at Brent Street School of Performing Arts, receiving her Diploma of Dance (focusing on Contemporary) with Honours. Anika made her professional debut in Sydney Festival in January 2022 performing a work Grey Rhino, choreographed by Charmene Yap and Cass Mortimer Eipper. Anika completed a post-graduate course at Transit Dance, performing works by Chimene Steele Prior, Prue Lang, and Paul Malek.

- Ruth Osborne, OAM

Ruth Osborne, outgoing director of Canberra’s QL2 Dance, was honoured with the richly deserved award of a Medal of the Order of Australia at the 2024 Australia Day Awards. Osborne has had a distinguished career over several decades, most recently since 1999 with Canberra’s outstanding youth dance organisation, QL2 Dance. Among her previous awards are an Australian Dance Award (Services to Dance), 2011; a Churchill Fellowship, 2017; and three Canberra Critics’ Circle Awards, most recently in 2023 for her performance and input into James Batchelor’s Shortcuts to Familiar Places. For more about Ruth Osborne on this website see, in particular, this link and, more generally, this tag.

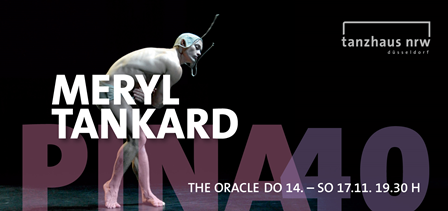

- Meryl Tankard: a new work

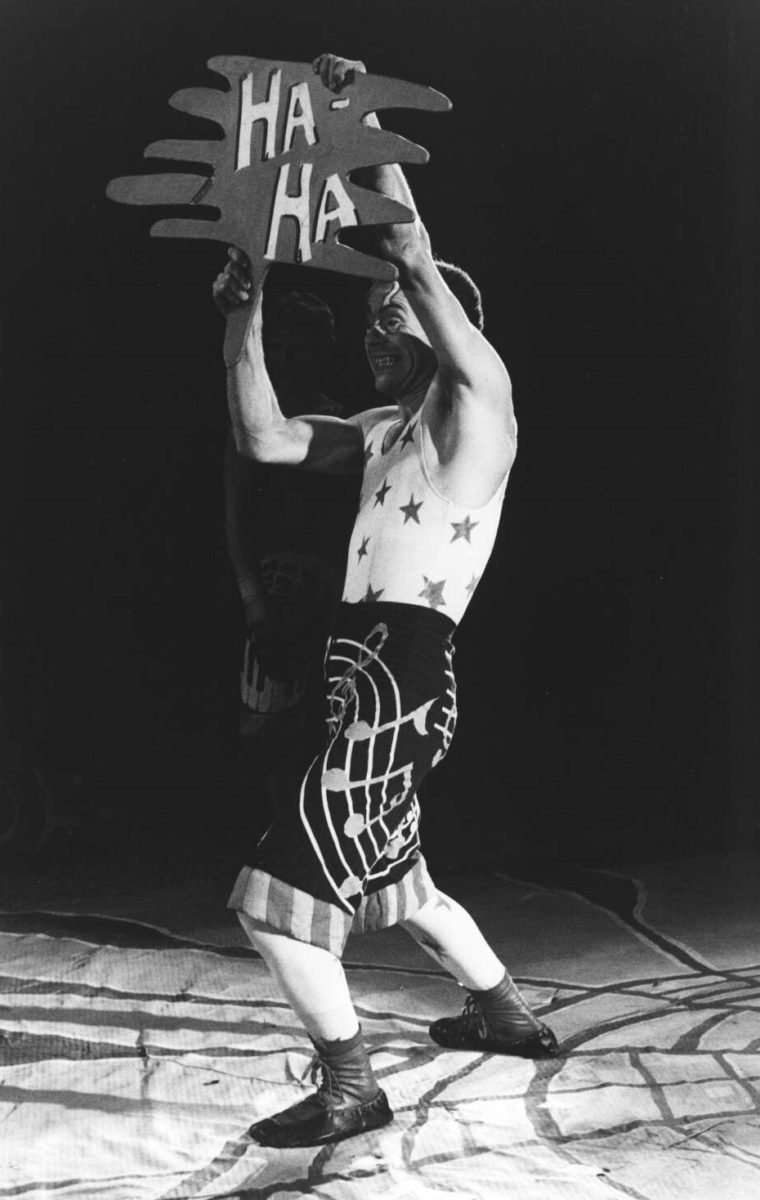

My colleague Jennifer Shennan has passed on the news that Ballet Zürich has just premiered a new work by Meryl Tankard. Called For Hedy, it is part of a triple bill called Timekeepers, which looks back to the artistic achievements of the 1920s. Other choreographers represented in Timekeepers are Bronislava Nijinska (Les Noces) and Mthuthuzeli November (Rhapsodies). More information is on the Ballet Zürich website.

- Press for January 2024

It has been a while since I have been able to add a section called ‘Press …. ‘ in a dance diary, but in January I had two items published in print outlets (which of course also appeared in an online version). The first appeared in Canberra’s City News, the second in Dance Australia for the 2023 Critics’ Choice section.

‘Flatfooted funding threatens company’s future.’ City News (Canberra), 4-10 January 2024, p. 17. Online version at this link.

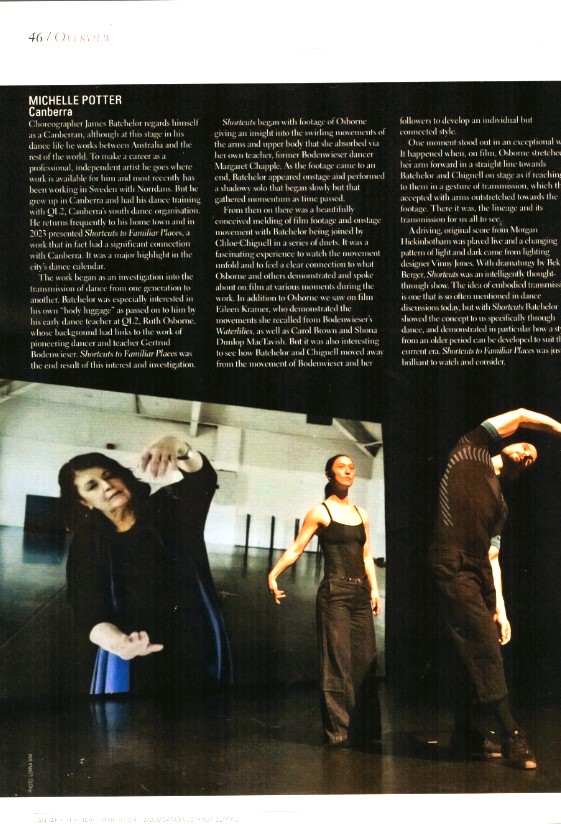

‘MICHELLE POTTER, Canberra’. Dance Australia: ‘Critics’ Choice’. Issue 242 (January, February, March 2024), p. 46. The text for this item is quite difficult to read against its black background, even in a blown-up version, so that text is inserted below next to a small image of the page.

Choreographer James Batchelor regards himself as a Canberran, although at this stage in his dance life he works between Australia and the rest of the world. To make a career as a professional, independent artist he goes where work is available for him and most recently has been working in Sweden with Norrdans. But he grew up in Canberra and had his dance training with QL2, Canberra’s youth dance organisation. He returns frequently to his home town and in 2023 presented Shortcuts to Familiar Places, a work that in fact had a significant connection with Canberra. It was a major highlight in the city’s dance calendar.

The work began as an investigation into the transmission of dance from one generation to another. Batchelor was especially interested in his own “body luggage” as passed on to him by his early dance teacher at QL2, Ruth Osborne, whose background had links to the work of pioneering dancer and teacher Gertrud Bodenwieser. Shortcuts to Familiar Places was the end result of this interest and investigation.

Shortcuts began with footage of Osborne giving an insight into the swirling movements of the arms and upper body that she absorbed via her own teacher, former Bodenwieser dancer Margaret Chapple.

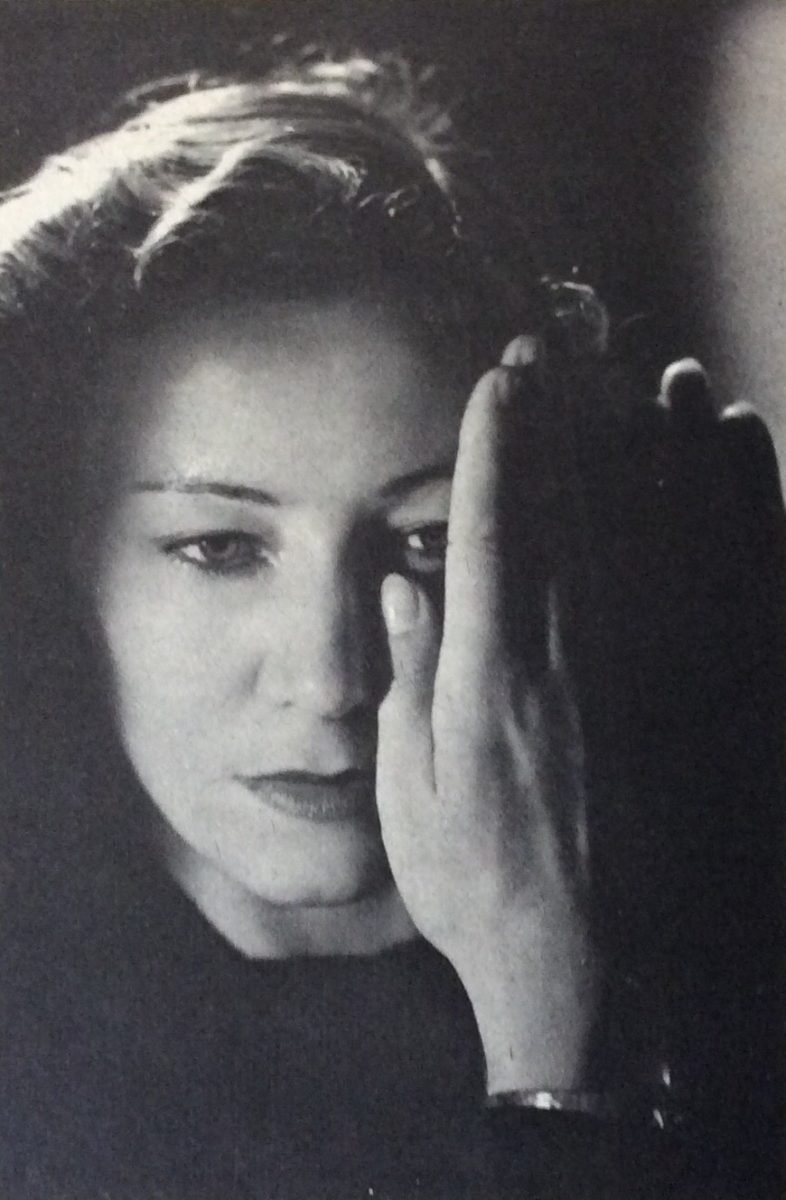

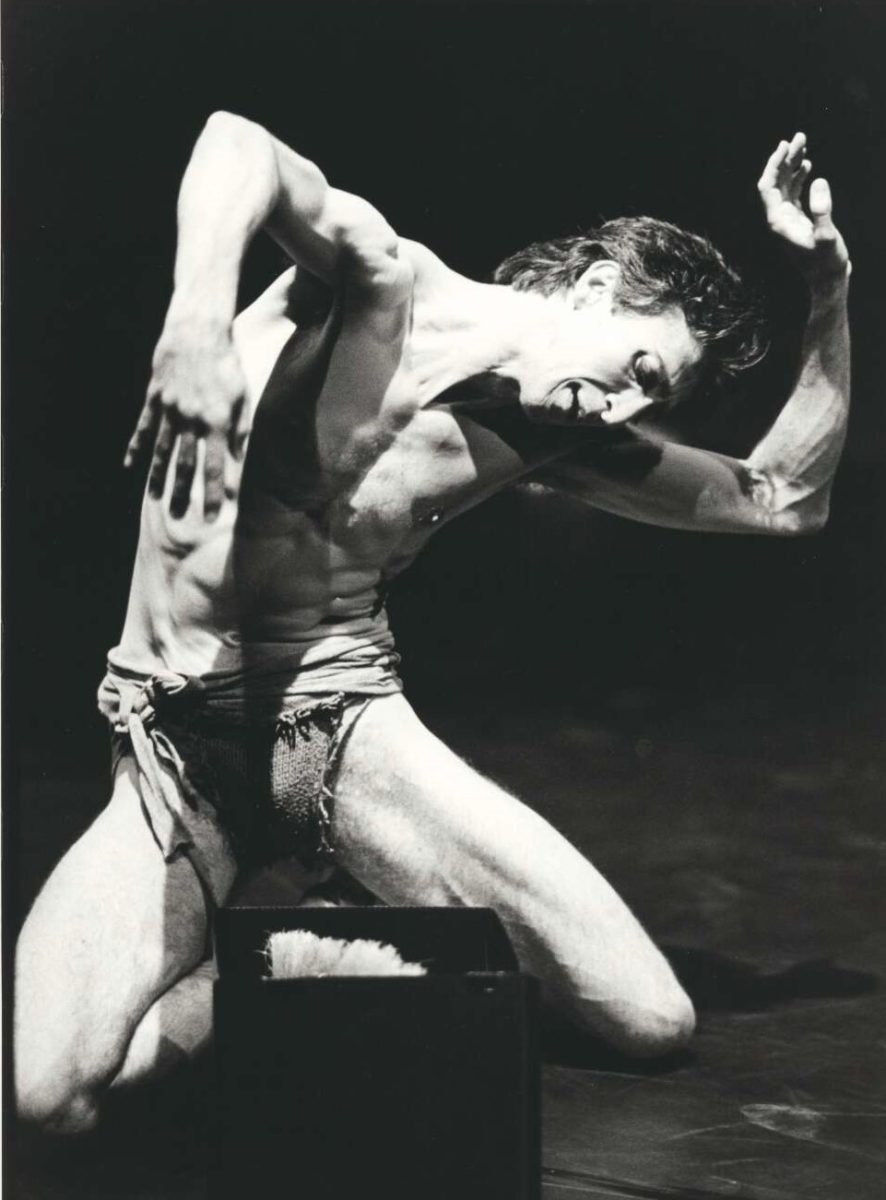

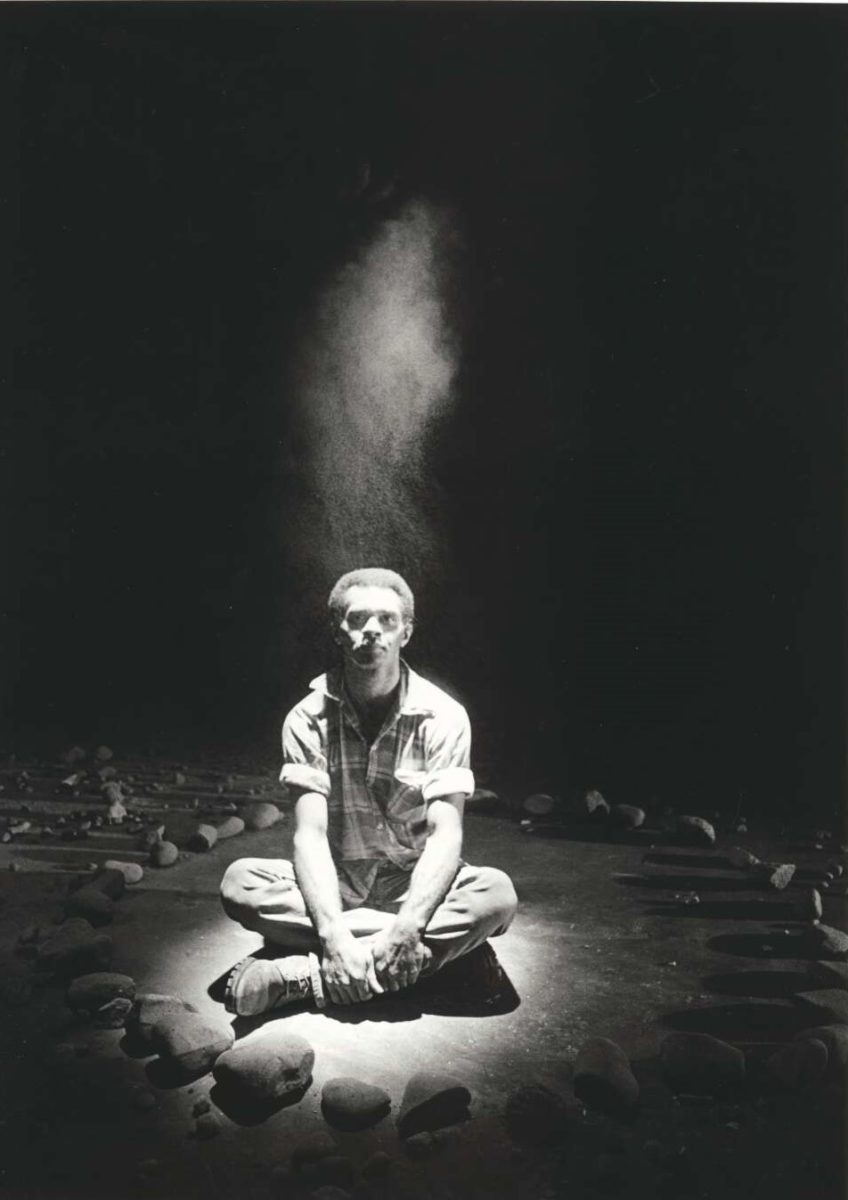

As the footage came to an end, Batchelor appeared onstage and performed a shadowy solo that began slowly but that gathered momentum as time passed. From then on there was a beautifully conceived melding of film footage and onstage movement with Batchelor being joined by Chloe Chignell in a series of duets. It was a fascinating experience to watch the movement unfold and to feel a clear connection to what Osborne and others demonstrated and spoke about on film at various moments during the work. In addition to Osborne we saw on film Eileen Kramer, who demonstrated the movements she recalled from Bodenwieser’s Waterlilies, as well as Carol Brown and Shona Dunlop MacTavish. But it was also interesting to see how Batchelor and Chignell moved away from the movement of Bodenwieser and her followers to develop an individual but connected style.

One moment stood out in an exceptional way. It happened when, on film, Osborne stretched her arm forward in a straight line towards Batchelor and Chignell on stage as if reaching to them in a gesture of transmission, which they accepted with arms outstretched towards the footage. There it was, the lineage and its transmission for us all to see.

A driving, original score from Morgan Hickinbotham was played live and a changing pattern of light and dark came from lighting designer Vinny Jones. With dramaturgy by Bek Berger, Shortcuts was an intelligently thought through show. The idea of embodied transmission is one that is so often mentioned in dance discussions today, but with Shortcuts Batchelor showed the concept to us specifically through dance, and demonstrated in particular how a style from an older period can be developed to suit the current era. Shortcuts to Familiar Places was just brilliant to watch and consider.

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2024

Featured image: A moment during the filming of Lake Song, directed by Sue Healey and choreographed by Elizabeth Cameron Dalman (seen in the foreground, coaching from the shore), 2023. Photo: © Sue Healey