Unintentionally, this month’s dance diary has a focus on retirements, resignations, the act of moving on and other activities associated with change. Dance is a moving art form.

- Adam Bull retires

Adam Bull, principal with the Australian Ballet since 2008, has announced his retirement from the company at the end of June 2023. Bull has danced major roles in classical and contemporary works across the range of the Australian Ballet’s repertoire including works by Kenneth MacMillan, George Balanchine, Graeme Murphy, Christopher Wheeldon, Wayne McGregor. Jiri Kylian, David McAllister, Alice Topp and others. His final performance will be in Melbourne in June in Topp’s new work Paragon, part of the 2023 triple bill Identity.

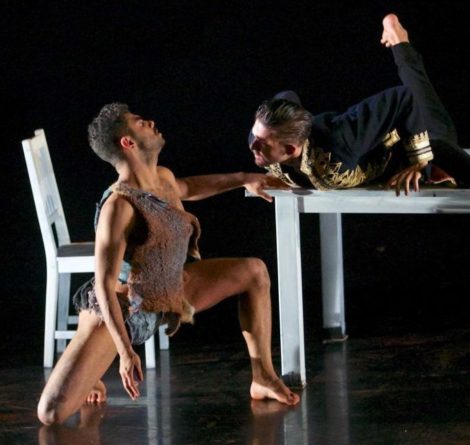

I have admired Bull’s performances whenever I have seen him, including in roles that have occasionally had not so much dancing in them. His performance as the figure of Death in Graeme Murphy’s Romeo and Juliet stands out for example. Then, still clear in my mind is his performance with Lana Jones in Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial, which did require a lot of dancing, as did his role in Alice Topp’s Aurum! And perhaps not so well known, since it only ever had eight performances in Brisbane, was his role of the Prince in Graeme Murphy’s The Happy Prince.

His artistry has crossed boundaries and his presence will be missed. Who knows when and where we might see him again?

Here is the Adam Bull tag for this website.

- Jacob Nash moves on from Bangarra

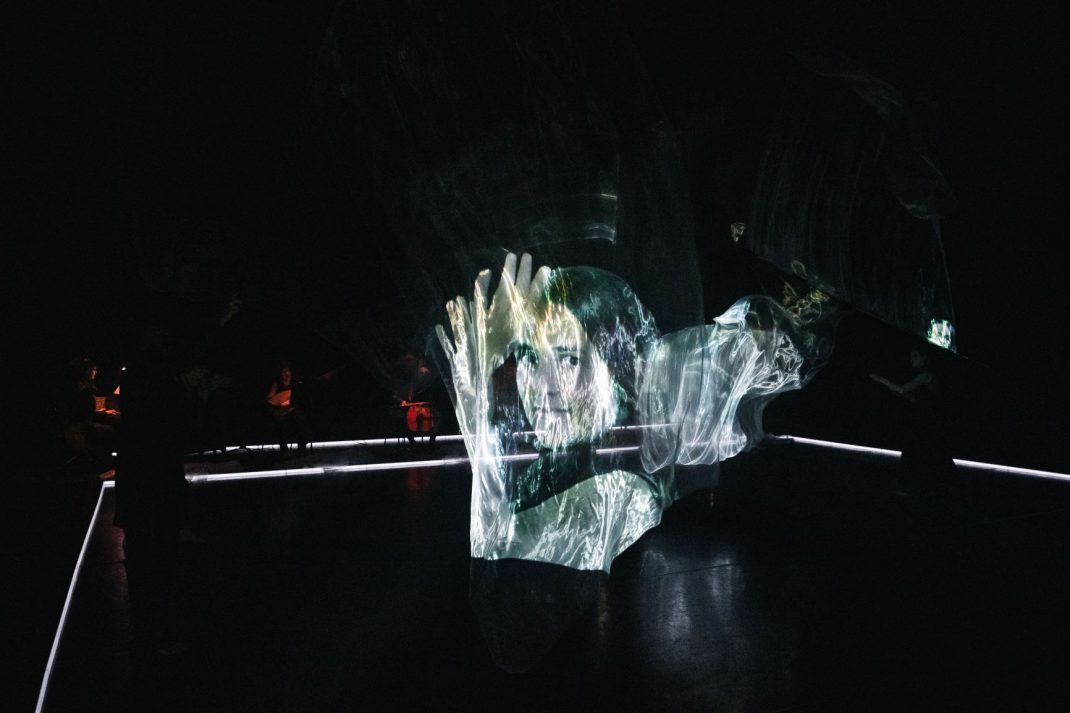

I was a little taken aback I have to say to learn that Jacob Nash, designer for Bangarra for more than ten years, is moving on. I have admired Nash’s contribution to Bangarra in many situations and in my discussion of Stephen Page’s 2015 film Spear I wrote of Nash’s contribution, ‘As in his sets for Bangarra’s live shows, Nash has brought to the film an understanding of the power of minimalism in design.’ But I also remember very clearly seeing an installation in an exhibition, Ecocentrix. Indigenous Arts, Sustainable Acts, in London in 2013, in which his contribution was not especially minimal. Nash’s work on this occasion was multi-layered and quite mysterious in its impact. Below on the left is an image of that installation, while on the right is his set design for the 2016 work Miyangan. I look forward to seeing more of Nash’s art wherever he continues to practice.

Here is the Jacob Nash tag for this website.

- Moves afoot in Western Australia

Artistic director of West Australian Ballet, Aurelian Scannella, will leave the company at the end of 2023. Scannella has been with West Australian Ballet for ten years and has been responsible for introducing many new works as well as staging the classics. Taking his place in 2024, for what is listed as a temporary appointment, will be David McAllister currently on a temporary appointment as artistic director with Royal New Zealand Ballet in Wellington following the retirement of former director Patricia Barker.

- More on Don Quixote

After watching the streaming of the 2023 staging of Don Quixote I was inspired to go back to watch again the film made in 1972. But I also went back to two oral history interviews I recorded for the National Library of Australia: one with Lucette Aldous in 1999, and one with Gailene Stock in 2012. Both Aldous and Stock talk about their experiences during the making of the film—Aldous at some length, Stock about a particular incident relating to Nureyev. Both interviews are available online and, with each one, the section of the interview relating to the film is easily accessible by keying ‘Don Quixote’ into the search box at the beginning of each interview (after accepting the conditions of the licence agreement). Happy listening. It’s worth it!

Lucette Aldous interview. Gailene Stock interview.

- Lynn Seymour (1939-2023)

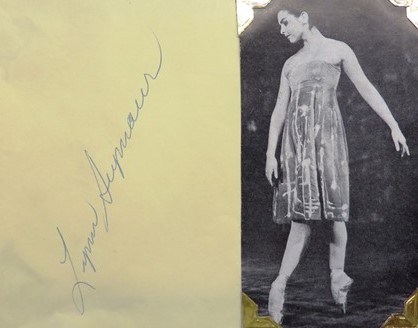

Canadian-born dancer, Lynn Seymour, has died in London aged 83. Seymour had an extensive career as a principal dancer with several major ballet companies. There are a number of obituaries available online and here is a link to the one I admire most, written by Jane Pritchard for The Guardian.

None of the obituaries that I have read mentions Seymour’s appearances in Australia and New Zealand during a Royal Ballet tour in 1958 and 1959 but she made her debut as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake during that tour and garnered mostly excellent reviews. My previous discussions of Seymour on this website, which relate to that tour, were written early in 2017 and have been somewhat controversial. But they continue to be accessed six years later. See this link, which also contains a link back to the controversy.

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2023

Featured image: Adam Bull and Coco Mathieson in Alice Topp’s Aurum. The Australian Ballet 2018. Photo: © Jeff Busby