Digital season, March–April 2021

When thinking about Tero Saarinen’s Third Practice, it helps to know (which I didn’t before reading up prior to watching) where the title comes from. Third Practice is performed to madrigals by Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi, played and sung by members of Helsinki’s Baroque Orchestra. Monteverdi’s musical style was referred to by his contemporaries as ‘second practice’ to distinguish his unprecedented compositional practice from that of his predecessors, who engaged in what was known as ‘first practice’. Monteverdi’s work sat at the point of transition between the Renaissance and the Baroque periods.

Saarinen set himself the task of examining, researching, and putting on stage a changing approach to creativity, a ‘third practice’ in dance and music and the collaborative arts, in order to add a new look and to give, to my mind anyway, an interesting new perspective on performance. He says, ‘ I’ve tried to preserve opportunities for “virtuoso freedom”. The third practice that we are talking about could mean a space for performers where their own skill and virtuoso flair facilitate risk-taking: discovering something new and unforeseen in your expressive idiom.’

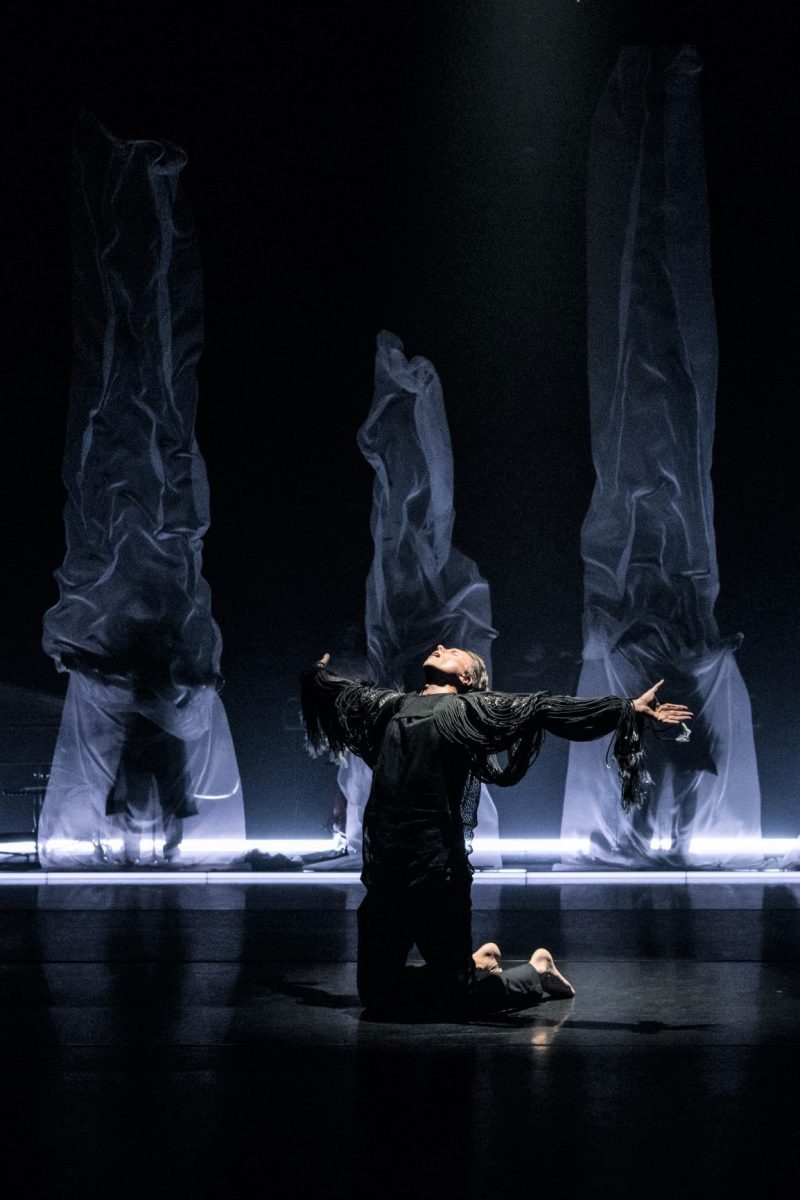

Third Practice is a multi-camera, filmed version, with projection design by Thomas Freundlich, of a stage production that premiered in Cremona in 2019. With music direction and arrangement by Aapo Häkkinen, it is performed by six dancers and six musicians with two soloists, a tenor (appearing live) and a virtual soprano. The collaborative elements are crucial from the very beginning. The lighting, by Eero Auvinen, cannot be ignored. It has been compared to the use of light and dark in the paintings of Baroque artists, especially Caravaggio. The use of side lights and down lights, and contrasting strongly lit, shadowy and misty spaces delivers a diverse, constantly engaging, often tantalising environment in which the work unfolds.

The costumes, designed by Erika Turunen, cross boundaries between the past and the present. The costume for the tenor soloist (Topi Lehtipuu) is masterful, although sometimes hard to see in media images. Its full sleeves and decorative finishing at the end of the sleeve recall Baroque-style shirts, but the materials are minimal and very contemporary in look. Similarly, the musicians wear Baroque-looking head gear, very appealing, but the rest of their costume again is mostly minimal.

Then there is the way in which the performing space is used. The virtual soprano, Núria Rial, appears in many parts of the space. We see her upstage and downstage; sometimes as a tiny figure in the background; hidden behind a floating piece of silk; reflected on the back of a dancer; and in other unexpected ways, including projected onto a silk hanging in the curtain calls. It is arresting staging and highlights the use of contemporary techniques to fill the space. The silks, while perhaps not an unusual item in contemporary dance and opera stagings, are nevertheless used in an exceptionally varied way. Sometimes they fall around the musicians lined up across the upstage area, or they engulf the dancers. At other times they are part of the choreography, occupying a space not usually filled with movement.

In terms of Tero Saarinen’s choreography, I was often transfixed by the expressive qualities of the movement. In the opening madrigal, the movement seemed jerky and somewhat puppet-like. I was reminded of figures from the Italian commedia dell’arte. Sometimes the movement seemed filled with a kind of extreme attention to detail both in the body movements and in facial expression. I was reminded of Baroque excess—the highly decorative aspects of Baroque church architecture and interiors, or Caravaggio’s fruit spilling out of the picture frame of his portraits. At other times, especially in a beautiful duet towards the end of the work, there was no excess, just calm, smoothly structured movement. Sadly, I am not familiar with the words of the madrigals and so was not able to determine whether the choreography was reflecting the meaning of the words, but it was a joy having the opportunity to create my own ideas anyway.

The standout performer in all of this was the tenor, Topi Lehtipuu. He sang live throughout whether he was standing, lying, crawling, kneeling or performing as one of the dancers. There was a moment when he was lying on the floor with dancers piled on top of him. He was still singing, this time in a duet with himself with the second voice a prerecorded one. Again it was an example of using technology to expand possibilities, but that Lehtipuu could sing so beautifully in such a compromised situation, compromised as far as his body was concerned, was astonishing.

Third Practice is an extraordinary work examining the endless possibilities of cross art form collaboration and the potential of dance to stand at the forefront of new explorations in the arts. It also made me reconsider the nature and potency of dance on film. Once again Tero Saarinen and his dancers and associates have given me an experience like no other. I love dance that expands the boundaries of my thinking. Third Practice does that and more.

Michelle Potter, 25 March 2021

Featured image: Topi Lehtipuu in a scene from Third Practice. Tero Saarinen Company, 2021. Photo: © Kai Kuusisto