1 May 2024 (and following national tour). St James Theatre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

This pedigree production of Swan Lake by Russell Kerr, the beloved father figure of ballet in New Zealand, was first staged on the company in 1996 and again in 2002, 2007 and 2013. Russell Kerr died in 2022 so this re-staging is the first not under his direction.

It proves a triumph on several levels, and is giving many a balletomane a sense of coming home. To some degree that involves the sumptuous sets and distinctive costumes by designer Kristian Fredrikson, which still carry as well as they did nigh on three decades ago. The cut and the cloth, the colours, weight and scale of all of Fredrikson’s work come from a singular vision.

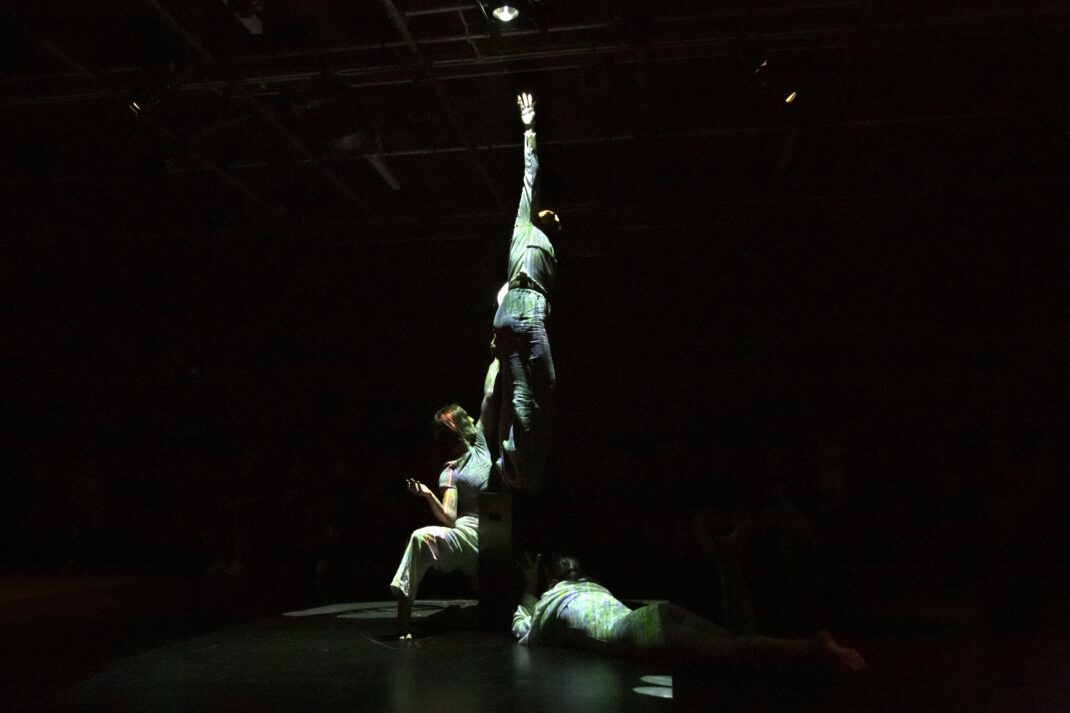

Mayu Tanigaito as Odette/Odile can trust her formidable technique to release an exquisite interpretation of the dual role. She conveys Odette’s yearning through superb control of port de bras, unfolding arabesques and in the beautifully held balances, which could have lasted even longer, holding her breath and ours. But after a hint of rubato with the masterful conductor Hamish McKeich holding the baton, you have to go where the stunningly beautiful violin solo, played by Donald Armstrong, is leading you. The pathos of doomed love and Odette’s courage to protect both the Prince, and her fellow victims, is rendered with a tenderness that was in splendid contrast with her sparkling duplicity as Odile. Pearl then diamond.

Laurynas Vejalis is a pensive Prince Siegfried, and I appreciate enormously the aesthetic restraint that he brings to his phenomenal technique. As a dancer he can do anything, as Siegfried he holds back, until he sights Odile that is. As the four-act ballet progresses this couple perform some of the finest pas de deux we have seen here in recent years.

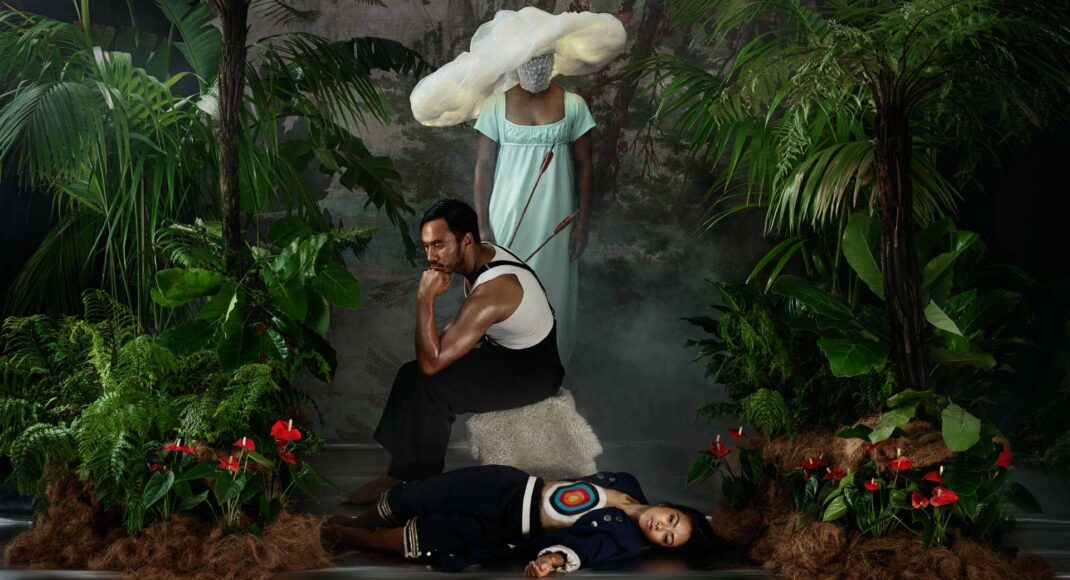

The ensemble of swans is impressive, many of them younger dancers who will be performing in their first Swan Lake. They may have missed Russell Kerr but they could not have a better introduction than this beautifully realised production. Character dances in the ballroom scene are very stylishly delivered and help build a rich and royal courtly atmosphere, all the more devastating when it falls out of the vertical and collapses into chaos. Von Rothbart wears the most magnificent cloak in history but I felt the mysterious and evil intent of his complex role could have been more convincingly conveyed.

Kerr’s production lifts Tchaikovsky’s sublime composition off the page and onto the stage, and the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra play superbly, with a number of fine players evident in the solos. The different sections of the orchestra are alive to the drama of lyrical and haunting or tempestuous and extrovert passages. Hamish McKeich holds it all together and the triumph belongs equally to him.

Much credit is due to the Company’s new artistic directorate for appointing Turid Revfeim as regisseur of Russell Kerr’s production. Revfeim is another of the country’s ballet legends—an accomplished dancer, teacher and artistic director of an independent ballet collective, a long-standing professional of great stamina and skilled diplomacy. Having worked with Kerr for years she is the perfect person for the job. The modesty apparent in her curtain-call speaks volumes, but as Edmund Hilary would say she ‘has an awful lot to be modest about’. Her program essay reminisces about Kerr’s inimitable way of working, and the high expectations he had of each dancer.

It is good too to be reminded of Shannon Dawson’s words about Kerr … ‘He is a parent of sorts, a father of dance, teaching the young, guiding the teenager and letting the adult go free, and the only thing expected in return is that you do your best.’

Kerr’s own insightful essay in the printed program proclaims ‘There are no swans in the ballet Swan Lake…’ explaining they are all women…’victims of an evil genius’. His reading offers an ambiguous ending to the ballet, suggesting that von Rothbart as the power of evil has been overcome, but perhaps only temporarily? Swan and Prince are together, but the misogynist magician will be back. He was conquered once, for now, but there may come a need to conquer him again. The resourceful lighting design by Jon Buswell contributes much here.

Jennifer Shennan, 3 May 2024

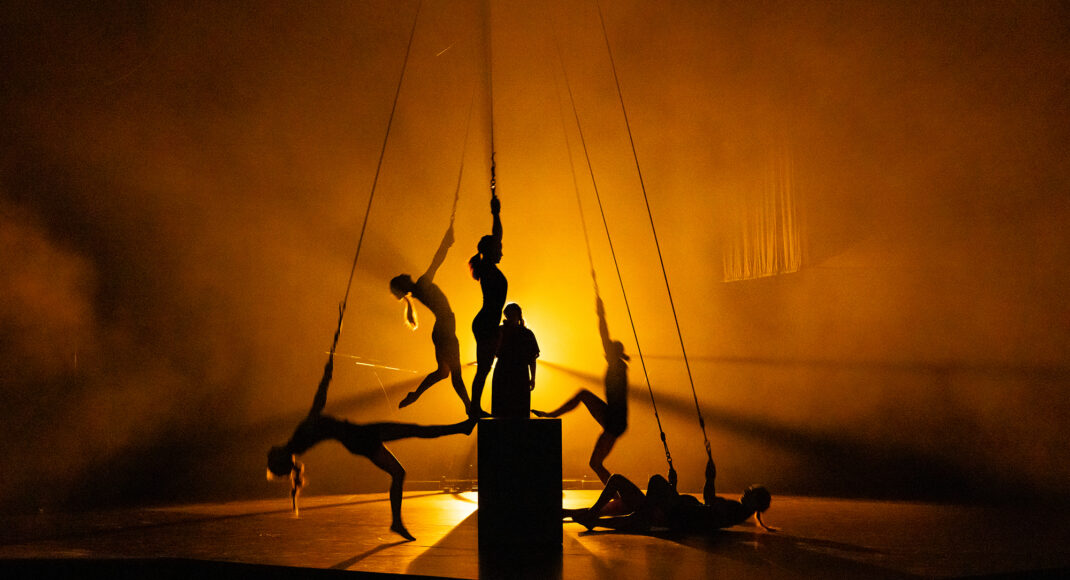

Featured image: Mayu Tanigaito as Odile and Laurynas Vejalis as Siegfried in Swan Lake, Act III. Royal New Zealand Ballet, 2024. Photo: Stephen A’Court