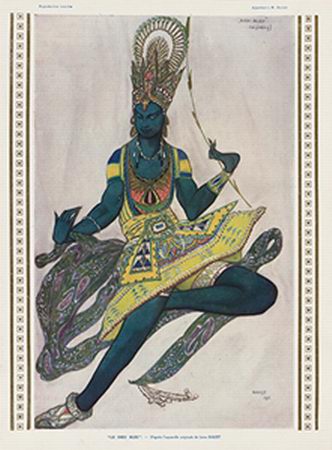

In the very glamorous exhibition, Ballets Russes: the art of costume, currently showing until late March 2011 at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, one of the most discussed items is the tunic from the costume for the Blue God from the ballet of the same name—in its French form Le Dieu bleu.

Its popular appeal rests largely on the fact that the tunic was worn by Vaslav Nijinsky, creator of the role of the Blue God and dancer and choreographer with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Not only was the costume worn by Nijinsky and as far as we know by no-one else, but traces of the make-up Nijinsky wore as the Blue God can still be found as marks on the inside the costume.

But we also know that the ballet was not a major success and was given very few performances after its 1912 premiere and quickly disappeared from the repertoire. That there were only a few performances of the ballet is both a blessing and a curse.

From a positive point of view it means that the costume, designed by Léon Bakst one of Diaghilev’s best known designers, is in excellent condition. While this situation reflects in part the exemplary conservation that has been carried out by the National Gallery’s conservation staff, it also reflects the fact that despite that the fact that the tunic is almost 100 years old it has not suffered from the wear and tear that constant use has on the fabric, decoration and stitching of dance costumes. Its excellent condition may also relate to the fact that it was made by two of the top Parisian costumiers of the time, M. Landoff and Marie Muelle. Madame Muelle in particular is known to have insisted that only the best quality fabrics be used and that decorative elements be appliquéd or embroidered rather than stencilled onto the fabric. She was also said to have had a secret metal thread that never tarnished.

A close-up look at the costume reveals that it encapsulates many of the principles that Bakst used throughout his design career, in particular a use of different textures in the one costume and daringly juxtaposed patterns and colours. He always made his interests, which included his understanding that dance was about movement, very clear in his designs on paper.

The costume is largely made from silk, satin, velvet ribbon, braid and embroidery thread, although set against the luxury silken fabrics are panels made from a simpler cotton or rayon material patterned with a floral, lotus-inspired design. The tunic’s dominant colours are pink, blue, gold and green and black and triangular and diamond patterns sit beside curves and half circles. Emerald green jewel-like sequins spill down strips of olive green braid.

Some parts of the tunic have been machine stitched. Others have been sewn by hand. The faux mother of pearl decorations along the hem of the tunic, for example, were hand sewn onto the fabric and the tacking stitches joining them together in a row can be seen where some of the decorations, now extremely fragile, have fallen off. The tunic has a row of metal fasteners, hooks and eyes, running right down the back—no zips, no Velcro in those days. Nijinsky would have simply held out his arms as the tunic was slipped on by his dresser, who would then have hooked him into the costume.

The Gallery’s collection also includes the gold headdress for the costume. It is equally as fascinating to study close up. Its double row of decorative points attached to a tight fitting skull cap is made of metallic gauze stitched by hand onto a wire frame with metallic thread—perhaps even with Mme Muelle’s untarnishable secret thread?

But in a more negative vein, because the work was performed on such a small number of occasions, what do we know about the choreography? Probably very little really. However, a number of historians have noted that Bakst and Michel Fokine, Le Dieu bleu‘s choreographer, had been deeply impressed by performances given in St Petersburg in 1900 by the dancers of the Royal Siamese Court and had incorporated choreographic and visual ideas from these performances into several Ballets Russes productions on which they worked, including Le Dieu bleu. Still photographs of Nijinsky show that static poses rather than a fluid and expressionistic form of movement may have been dominant, recalling the dance style of the Siamese dancers.

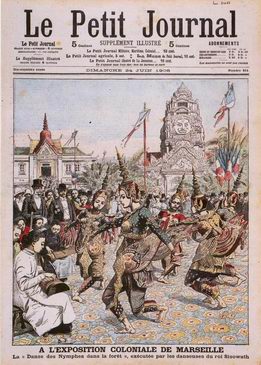

But another dance troupe from the other side of the world probably had just as much influence on the creation of Le Dieu bleu as did the dancers of the Royal Siamese Court. In 1906 the Royal Cambodian Ballet came to France for the Colonial Exhibition staged in Marseille, Cambodia being at that stage a protectorate of France. The Cambodians gave several performances in Paris in July of that year, just as Diaghilev was in Paris preparing for his major exhibition of Russian paintings, which was presented a little later that year at the Salon d’automne. It is hard to imagine that Diaghilev and his team would have been unaware of the Cambodians. They caused a sensation in Paris and had a major influence on a number of French artists, including the sculptor Auguste Rodin who followed the company to Marseille and executed a major series of drawings of the dancers. Many newspapers, including the Parisian daily Le Petit Journal and the influential Le Petit Parisien, carried news of and advertisements for the Cambodians and most carried drawings and posters of the dancers against a background of Cambodian temples.

Bakst appears to have drawn on these printed sources for his backcloth, which features a huge rock face carved with faces of gods. It clearly recalls the posters in Parisian newspapers, which in turn recall the huge faces carved into the rock at the gateways to the Angkor Thom temple in Siem Reap, Cambodia.

Costumes for subsidiary characters in the ballet as held by the Victoria and Albert Museum and on display in their London exhibition, Diaghilev and the golden age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, confirm that Bakst was indeed influenced by the interest in Cambodia that was generated in 1906. In particular the costume for a Little God, illustrated on p. 79 of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s catalogue, shows a towering headdress with four god-like faces smiling beatifically out to the potential auditorium. The headdress looks totally unlike anything a Cambodian dancer would have worn (or currently wears). The faces look a little more like Western-style putti than anything else and one can’t help but wonder whether Bakst only ever saw the cover of French magazines of the time and never the dancers themselves. However, the Cambodian influence is clearly there.

But the tunic for the Blue God will always evoke the man who created the role and who caused so many scandals for the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev, that is Vaslav Nijinsky. The power of his name, like that of Anna Pavlova, will always make anything associated with him appealing to a wide spectrum of the population. One of Nijinsky’s colleagues, the ballerina Lydia Sokolova, has described in her memoirs the first sight the audience would have had of Nijinsky as the Blue God. She writes that he was seen ‘at the top of a flight of wide steps at the back of the stage, seated on a throne with legs crossed, holding a flower’. He was wearing the tunic now on display in Ballets Russes: the art of costume.

© Michelle Potter, 27 December 2010

This post is an amplified and enhanced version of my article ‘Homage to the Blue God’ first published by The Canberra Times on 18 December 2010.

The website for the National Gallery’s exhibition is at this link.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bell, Robert (ed.). Ballets Russes: the art of costume (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia 2010)

- Buckle, Richard (ed). Dancing for Diaghilev. The memoirs of Lydia Sokolova. Paperback edition (San Francisco: Mercury House, 1989)

- Misler, Nicoletta. ‘Siamese dancing and the Ballets Russes’ in Nancy van Norman Baer (ed.), The art of enchantment: the Ballets Russes 1909–1929 (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1988), pp. 78–83

- Musée Rodin. Rodin and the Cambodian dancers: his final passion (Paris: Editions du Musée Rodin, 2006)

- Pritchard, Jane (ed.). Diaghilev and the golden age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929 (V & A Publishing, 2010)

Comments on this post are now closed. The discussion continues on part two.

The issue of whether anyone else wore this costume is intriguing. Picture 356 in the volume “A Picture History of Ballet” by Arnold Haskell [pub 1954] shows Karsavina, Vera Fokina and Michel Fokine in a posed photo from Le Dieu Bleu. Fokine is clearly wearing either the costume belonging to the NGA or another one based on the same Bakst design.

Also, the Russian edition of Fokine’s memoirs carries a photo from Le Dieu Bleu of the same three dancers but in a different pose. Once again the costume is remarkably similar.

Neither photo carries a company credit. I don’t know russian but the caption in the memoirs seems to identify the performers and ballet title only.

On checking the performance lists in the French publication “Les Ballets Russes” [Auclair/Vidal 2009] it would seem that Le Dieu Bleu did have a life throughout Europe during the tours subsequent to it’s Paris premiere. It was also included in the printed publicity lists for the American tours but does not seem to have made it on to the stage there.

Fokine did restage his works for other companies but mainly the major successes. It would appear unlikely that another company would foot the bill for the outlay required for this ballet.

So perhaps the choreographic creator of the work did on occasion get to wear this costume.

Well this is interesting. The V & A also has a Blue God costume and here is a quote from Jane Pritchard’s blog posted on 13 September 2010 as V & A curators were ‘filling the Nijinsky case’:

‘Our Blue God costume is also a puzzle-its not the one Nijinsky is photographed in-but nor is it the one Mikhail Fokine was photographed in. The other version of the ‘Nijinsky’ costume is in Australia. Oh and it does not match the costume for the Swedish dancer, Jean Borlin, when he danced a version of Nijinsky’s solo’.

Annoyingly, there doesn’t seem to be an illustration of the V & A’s costume in their exhibition book. But I remember being surprised when I saw it since it was definitely different from the Australian one.

The best Nijinsky Dieu bleu photograph in terms of size and reproduction quality that I can find from amongst my books is in A Feast of Wonders on p. 182. A comparison with the NGA’s illustration of the tunic on p. 114 of their catalogue seems to make it clear that the tunics are the same in both illustrations. The NGA does not have the belt shown in the photograph, nor the undershorts, and its headdress is different–in fact I need to go back and look at the headdress with A Feast of Wonders in hand. I have little doubt, however, that the costume now on display at the NGA is the one in which Nijinsky was photographed. So, although I guess one can never be absolutely sure of anything, I do think the Australian costume is the one Nijinsky wore.

The best reproduction I can find of Fokine in the costume is on p. 55 in The Art of Extravagance, a publication from the Dansmuseet in Stockholm. Fokine is posing with Karsavina and his costume also looks very much like the NGA’s one, although Fokine may be wearing a different belt from the one in the Nijinsky photograph. In fact it looks just a little like a ‘make-do’ item for the photograph. The caption to this illustration gives the date as 1912 and it looks to me like one of those sepia postcards that were common around the early part of the twentieth century. It was published in Berlin according to an attribution printed on the bottom of the postcard.

Now Diaghilev and company were in Berlin in the early months of 1912, according to Bronislava Nijinska in her Early Memoirs. She indicates that Fokine choreographed Karsavina’s role in Le Dieu bleu in Berlin before Karsavina returned to the Maryinsky in February to fulfill engagements there. So, one wonders whether the costumes had already been made in Paris from Bakst’s designs before the company left there at the end of 1911. The design for the Blue God reproduced in the NGA’s catalogue is actually dated 1911 on the design (in Bakst’s handwriting?). Perhaps Fokine took steps to have a postcard made before Karsavina left for St Petersburg? But why not get Nijinsky into the costume he would wear? Nijinsky was apparently in the throes of working on Faune during January so perhaps he was not in the best of moods for such an occasion? Or maybe Fokine just wanted to be photographed in it?

Anyway, this is all speculative and maybe someone who knows more about Le Dieu bleu than I do, especially about its performance history, will come to the rescue?

An interesting thing regarding the Dansmuseet picture is that Fokine is wearing the specially designed ballet slippers for this costume. They can be seen, as Bakst designed them, in the costume design reproduced in the NGA catalogue. In no photo of Nijinsky in the costume, and there are several, does he seem to be wearing these slippers. And I have also wondered about the blue body makeup as this does not appear to have been applied for any of the photographic sessions.

The costume that Fokina is wearing in the photo in the Haskell book I referred to previously is also reproduced in the Dansmuseet catalogue. It belongs to The Goddess and was originally worn by Lydia Nelidova.

So perhaps here we have an alternate cast for Dieu Bleu, at least as far as Blue God/Goddess are concerned, although I believe I have read somewhere that both Max Frohmann and Adolf Bolm played the bridegroom role.

Aren’t the slippers remarkable? I wonder though whether they got in the way of the dancing? That little ‘collar’ may well have impeded the movement and maybe Nijinsky refused to wear them? As for the blue make-up, imagine what it was like putting it on, and even worse, taking it off. No wonder it never appears in the photographs.

The Fokina/Nelidova costume for the Goddess is quite beautiful for the most part I think (not sure about the headdress with that trailing scarf – again how did they dance in it?). But it has been interesting lining up all these catalogues and seeing such a range of costumes together. The thing that emerges for me is the huge array of styles that Bakst was required to design, obviously reflecting the libretto with all its cacophony of characters!

I think it is worth pursuing the idea of an alternate cast, although I can’t help thinking of previous posts on this website re photography. I am reminded of the kind of publicity shots of which the Australian Ballet is currently very fond in which dancers who may or may not be cast in productions are shown in poses and costumes that never appear in the final production. If the photographs we have been discussing were for publicity purposes, at least they bear some relationship to the final work. But it would certainly be good to find or construct a performance history.

Your mention of Jane Pritchard’s blog has sent me in perusal of it. She makes mention of the Theatre Museum’s “Spotlight” exhibition which took place at the V&A in 1981. The catalogue entry for the Blue God’s costume for this exhibition mentions that at that time the V&A had 2 of the Blue God costumes. The one displayed and believed at that stage to be Nijinsky’s is catalogued as having been a gift of Nadia Nerina’s to the museum. The entry also states that the other costume was acquired at a Sotheby’s auction on 13 June 1967 where it was catalogued as having been Nijinsky’s. But an interesting comparison is made between the 2 costumes indicating different colourings and inferior materials on the 1967 one. The 1967 costume also appears to be a larger size and it is suggested that it may have been Fokine’s.

The NGA costume was purchased in 1987. Was this a third costume or was it the second Theatre Museum costume which was deaccessioned ?

Well the plot thickens!

Comments retrieved from backup.

Adrian Ryan said:

Dec. 31, 2010

Just to return to the Dansmuseet catalogue photo of Fokine and Karsavina in Blue God costumes for a moment. Could this photo be from 1914 ? As we know, after Nijinsky parted ways with the company in late 1913 and Fokine returned around the start of 1914, one of Fokine’s conditions was that he dance the major Nijinsky roles [and that Fokina get to dance some of the Karsavina roles]. And there are a large number of photos and postcards of Fokine looking a bit uncomfortable as Spectre/Golden Slave/Harlequin etc. which seem to date from this period when new publicity would have been required. And as “Dieu Bleu” was performed in Berlin on March 11 and March 13, 1914, perhaps this title was included in the photo shoots along with the other roles.

One thing though is that the background in the Dansmuseet photo does not seem to be the same as for all the other Fokine/Fokina images from this period that I have seen. There is a good selection of them in Anna Winestein’s “Ballets Russes and the Art of Design” book. In fact the background seems to be similar to the photo in the Haskell book I referred to in a previous post. This photo shows a kind of grotto with steps and a bench on which the Goddess sits with Blue God at her feet on her left and the Karsavina character at her feet on her right. This could have been a makeshift arrangement for the photo shoot of course. But I wonder if Fokine and Karsavina stood up and took a new pose in front of this setting and the resulting photo is the Dansmuseet one. It may be that at this later stage Fokine is wearing his own costume in these photos.

Michelle said:

Dec. 31, 2010

It’s certainly possible that the Dansmuseet catalogue photo is from 1914 and looking again at the double page on which it occurs in the catalogue it seems that it is probably the ballet to which the date 1912 is being attributed rather than the postcard. I had assumed previously, and hurriedly I am ashamed to say, that it was the postcard that was being dated. And looking again at the costume Fokine is wearing, the decorative elements along the bottom edge of the tunic are different (I think) from the NGA costume. So this may well be Fokine’s own costume, which explains a lot.

So how many Blue God costumes are there I wonder? And where is Fokine’s one (if indeed he had one of his own)? And who wore the one the V & A has on show?

Adrian Ryan said:

Dec. 31, 2010

There is a good quality colour reproduction of the V&A Blue God costume in the book “Ballets Russes” by Richard Shead. At least the picture credit is for the V&A. This book was first published in 1989. Michelle is certainly right about it’s being very different to the NGA costume. I am presuming this is the same one now on display at the V&A. The use of yellow is far more pronounced and more in keeping with the tonalities of Bakst’s design. However the breast area seems to bear no resemblance to the design.

Adrian Ryan said:

Dec. 31, 2010

To return to “Le Dieu Bleu” performances subsequent to it’s Paris premiere, the March 11/13, 1914 Berlin performances seem to be its last. However, the Souvenir Programme for the first “Serge De Diaghileff’s Ballet Russe” tour in America in 1916 contains the following :

A costume plate of Bakst’s design for a “Pelerin” [Pilgrim] from Le Dieu Bleu

A plot synopsis and credits for score, designs libretto.

And the cover contains an elaborately embossed design by Bakst, highlighted with gold, of the Goddess from Le Dieu Bleu seated in a lotus position.

So it would appear that this title was meant to take its place amongst the repertoire but according to all available performances lists it did not do so. Nijinsky was not with the company on this first tour. Bolm and Massine seemed to be sharing his roles. Perhaps a new Blue God costume was made for this tour. Certainly the costume for Zobeide as worn by Revalles is quite different from that of Rubinstein or Karsavina. But here I suppose it may have just worn out.

Jane Pritchard said:

Jan. 1, 2011

Oh dear thousands of comments to make and not much time at present. Lets not get into the changing evolution of Schéhérazade and Zobéïde’s costumes yet – Bakst must have redesigned this to flatter each of his dancers.

1. The original costume for Ida Rubinstein 1910

2. The Karsavina/Astafieva version for autumn 1911 (I don’t know what Roshanara who also dance the role this season at the ROH wore) This is the Karsavina version currently on display at the V&A

3. The Karsavina version for 1912

4. The Vera Fokina version originally for performances for Royal Swedish Ballet in 1913 and then worn with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1914

5. Schéhérazade was redesigned in 1915 (see credit in programme) this is when the Flora Revalles version comes in

6. This is modified for Lubov Tchernicheva (and since she continues to dance the role it settles down as the costume)

What this alerts us to is that there is often not a fixed version of one characters costume in a successful ballet – and do critics ever alert audiences to changes?

And on the subject of Fokine & Fokina photos in The Ballets Russes and the Art of Design many were actually taken in Stockholm when Fokine mounted Cléopâtre, Les Sylphides, Le Spectre de la rose, Le Carnaval and Schéhérazade there when spurned by Diaghilev 1913-14.

But to the challenges of Le Dieu bleu, a ballet full of questions and one for which a contemporary viewer (A. E. Johnson) commented that the published programme synopsis was not the action realised on stage. I recall once having an argument with a significant choreographer when his synopsis was clearly not what happened in performance but he insisted it was published none the less – what a disservice to his audience and posterity.

Whatever one thinks about Herbert Ross’ film Nijinsky it contains a wonderful scene in which we see a dress parade of the costumes for Le Dieu bleu followed by a petulant Fokine (played by a young Jeremy Irons) complain to Léon Bakst that Bakst is trying to ruin the ballet by over-designing it. This may not be an historically accurate meeting but there is a real truth to it. Le Dieu bleu to me appears to be such an old fashioned production drowning in display. I find it fascinating that when the French start contributing to the Ballets Russes productions it takes thema while from them to break away from their balletic past. Much of Le Dieu bleu was procession and mime Beaumont described the one performance he saw as having ‘dull’ music, ‘uninspired’ choreography and containing ‘too much miming and posing, too many procession’. The demons and reptiles were ‘reminiscent of a Christmas pantomime’ and comic. Gosh aren’t I excited that I’ll be able to see Wayne Eagling’s new version of this ballet at the London Coliseum in April!

But to sort out some facts. Le Dieu bleu did not receive a large number of performances but it was presented in Paris (1912), London, Monte Carlo, Buenos Aires and Rio de Janiero (all 1913) and all these performances featured Nijinsky in the title role. It was also given two performances in Berlin in 1914 when Nijinsky was no longer in the company thus the title role was performed by Fokine and his wife, Vera was the Goddess (a role created by Nelidova).

I found it extremely valuable when told I was mounting a Ballets Russes to compile a day-to-day itinerary for the Company so that I understood which productions were performed where and how often. And on the subject of itineraries, just as we say in Britain you wait ages for a bus and then three come along – the same happened with the Ballets Russes performances. Sarah Woodcock published her version in The Dancing Times; the Paris Opéra’s exhibition book les ballets russes included a version by Boris Courrège and team and my own (the most complete for which I happily acknowledge assistance from Roland John Wiley, Andrew Foster and others) was in Dance Research Volume 27 (2009) which is available through JSTOR on line.

There appear to be two sets of photographs for Le Dieu bleu – those taken in a Parisian studio by Walery at the time of the 1912 premiere in Paris. These were initially reproduced in the souvenir programme (produced by Comœdia Illustré) and serve to document the creators of the ballet in their costumes – I feel certain many of these photos were taken to show Bakst’s magnificent costumes rather than the dancers.

Then there are the Berlin photographs taken in 1914 which were reproduced as postcards and reproduced as a full page spread in The Sphere, London 23 May 1914. I think these are taken posed on stage and what we are seeing is the Lotus pool and the golden staircase of the set. I think our god and goddess are on their plinths on which they rose from the pool (Fokine’s lower right leg is hidden) to make their first appearance. The review in the Observer 2 March 1913 p.8 refers to ‘the Lotus flower that dreams in a large basin. From its petals the Goddess arises; at her side the blue god who proceeds to charm the denizens of the den to tameness. The tunes of his pipe and his elaborate dance play the part of Orpheus with considerable effect.’ At the end of the ballet the ‘Goddess returns to the heart of the Lotus and the blue god goes in another direction to the Indian Walhalla, with the assistance of a golden staircase that conveniently appears behind the opened rocks’. I would actually suggest that the best published description of the ballet appears in A.E. Johnson’s book The Russian Ballet (with illustrations by René Bull) London: Constable, 1913. pp. 163-177

But to return to the costume as seen in the photos . Nijinsky and Fokine are not wearing identical head dresses – once again, as with the shoes it is Fokine whose head dressis closest to the Bakst design note the drop ‘pearl’ decorations like ear-rings hanging from it.

I agree that of the two known extant versions of costumes for the Blue God – the Canberra version matches the tunic in both sets of photographs. Please note it was never in the V&A’s collection we did not de-accession it. The Canberra costume appeared on the cover of the catalogue for first major Ballets Russes Sale 13 June 1967 when according to the published lit of Prices and Buyers’ Names it sold for £900 to a Mrs Gibson – incidently the costume can be glimpsed in the background of the photo of Marie Rambert in Lubov Tchernicheva’s Pas d’acier jackets at a preview of the sale on p.167 of our exhibition book. The Canberra version was on display in the amphitheatre foyer at the Royal Opera House for years so I am amazed that it is still in such good condition.

The British version is extremely fragile and was one of the two last costumes worked on, the other being one of Matisse’s costumes for Le Chant du Rossignol. Both demanded very long hours of work and were not ready to be photographed for our book (not catalogue) to accompany the exhibition. The old photo of it as reproduced in Shead is horrid. I’ll get together more specific material on our version of the Blue God costume and get back to you on this. W also have a lot of other costumes for this production.

Adrian’s suggestion about new costumes for the USA tour is an interesting speculation – I just wish I knew how many of their costumes the Ballets Russes had access to when they re-formed in 1915 – all the productions that year are described as being ‘redesigned’. I would love it if that also made sense of the mystery concerning the two versions of Le Festin costumes but it does not. So over New Year I’ll have to do some more thinking about the costumes.

I’ll finish these ramblings by including the copy on the labels for our four Dieu bleu objects in the exhibition; the painting of the set, a costume design (in the Bakst section) and two costumes (in the Nijinsky case).

Le Dieu bleu 1912

Diaghilev never let concerns over authenticity override artistic impact. Le Dieu bleu (‘The Blue God’ or Krishna) was designed by a Russian in a vaguely Indian setting, with a score by a Venezuelan composer for a French audience. Bakst’s designs mixed elements from various south Asian cultures. The faces on the stone cliff resemble those on the Bayon Temple of Angkor Thom in Cambodia.

Oil on canvas

Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

Private collection

Costume design for a young Rajah in Le Dieu bleu 1912

Bakst’s designs for Le Dieu bleu were among his most elaborate, but the ballet was old-fashioned in its emphasis on design at the expense of dancing. His costume for a young Rajah, a character not individually named in the programmes, shows fantastic detail in the feathered turban, pearl decoration and stylised shoes.

Pencil, watercolour and gouache

Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

V&A: S.338-1981

Costume worn for Le Dieu bleu 1912–14

The Blue God (1912), a ballet based on Krishna, was created for Nijinsky. His solo included poses inspired by Hindu sculpture, and his costume featured a closed lotus flower among sunrays on the appliquéd torso. Nijinsky and Fokine, who took over the role, were each photographed wearing different versions of the costume. The example here is more richly decorated.

Watered silk, inset with satin and embroidered with mother-of-pearl

Designed by Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

V&A: S.547-1978

Costume for a Little God in Le Dieu bleu 1912

Léon Bakst’s lavish costumes emphasised design over choreography in The Blue God. A child performer wore this costume, whose tall headdress reveals the influence of Cambodia in its pyramid shape and sculptural forms.

Gold knit, satin and gold-painted decorations

Designed by Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

V&A: S.613 to B-1980

Michelle said:

Jan. 1, 2011

Comments on this post are now closed. The discussion continues on part two.