- Illume. Bangarra Dance Theatre

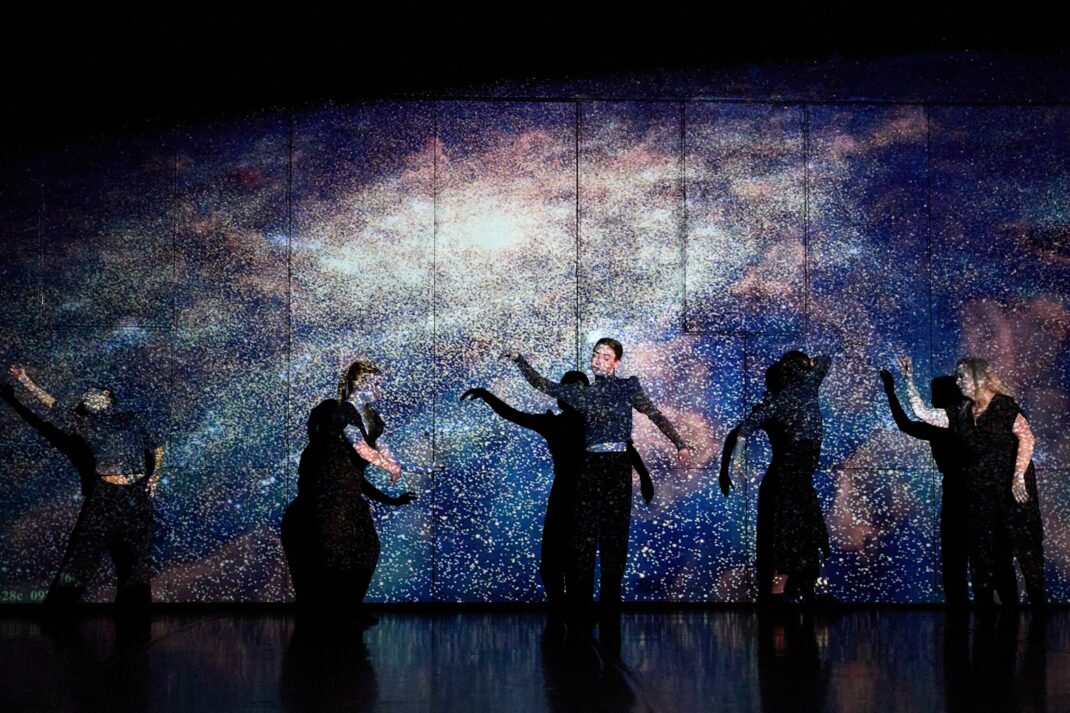

The May edition of Qantas Magazine carried a two page spread on visual artist Darrell Sibosado, who is the designer for the forthcoming Bangarra production, Illume. The article, written by Kate Hennessy, had the title ‘This First Nations visual artist is shining new light on ancient ceremonial carvings’. From reading the article, I discovered that Darrell Sibosado comes from the Dampier Peninsula in Western Australia and that his family is one of carvers, who, across time, have created designs on pearl shells to be used in particular ceremonies. In the article Sibosado says that, historically, the work of his family is ‘about capturing the iridescence, shine and many layers of the pearl’. It will be interesting to see how this background translates into his designs for Illume, in which Bangarra suggests we will ‘step out of the shadows and into the phenomena of light—the central life force of our planet’.

illumine, with choreography from Frances Rings, opens in Sydney on 4 June 2025 before travelling elsewhere. See the Bangarra website for further details of the creators and of the performance schedule.

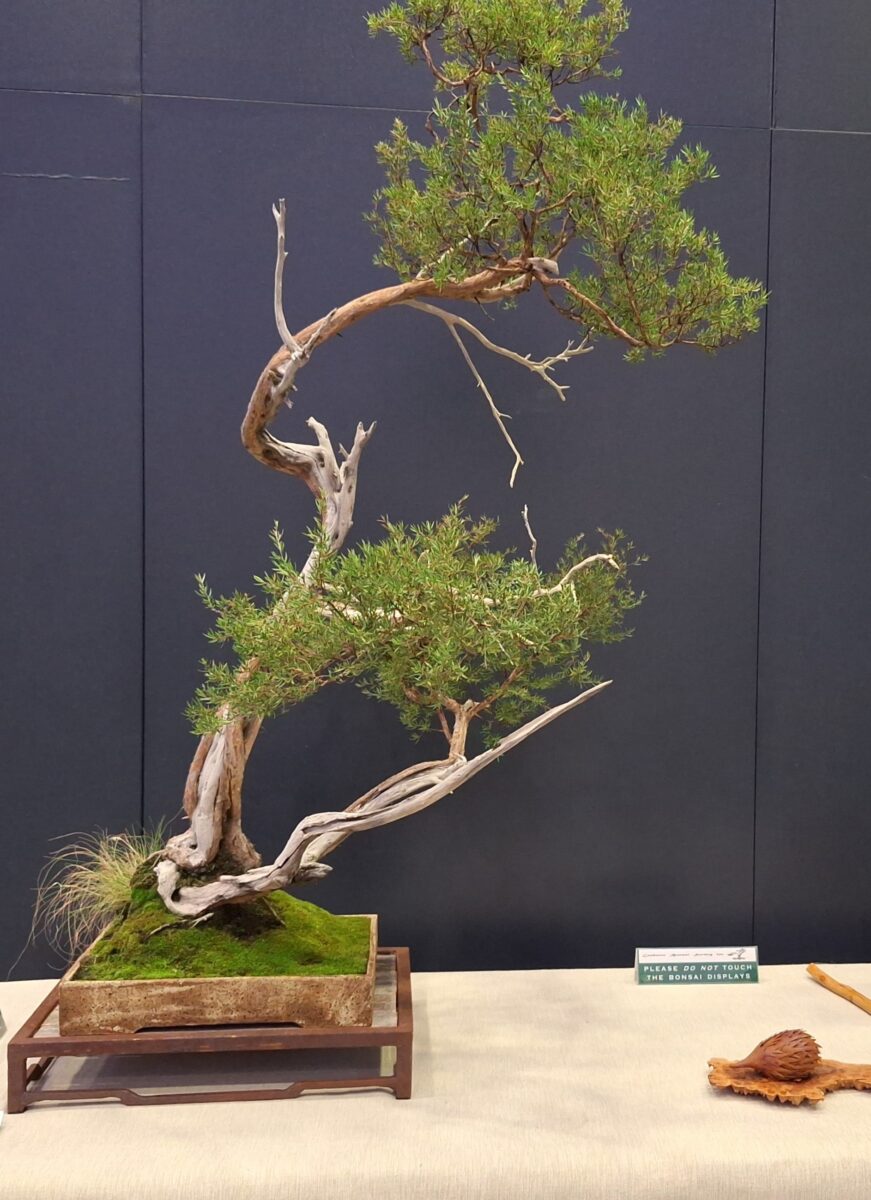

- Bonsai Ballerina

Jennifer Price was a dancer in Chicago but, after retiring, became transfixed by the art of Bonsai and took up the study of the creative procedure behind that art form. She was recently in Canberra for the 2025 AABC National Bonsai Convention, which celebrated (amongst other things) the 50th anniversary of the Canberra Bonsai Society. The convention closed with an exhibition (free to the public) and the images below are two of the items that were on display in that exhibition.

I know very little about Price’s dance background, and probably less about the art of Bonsai, but from the often stunning examples on show in the exhibition I was not surprised that a former dancer was moved to look deeper into the art form. I was attracted of course by the name that the media gave to Price—’Bonsai Ballerina’!

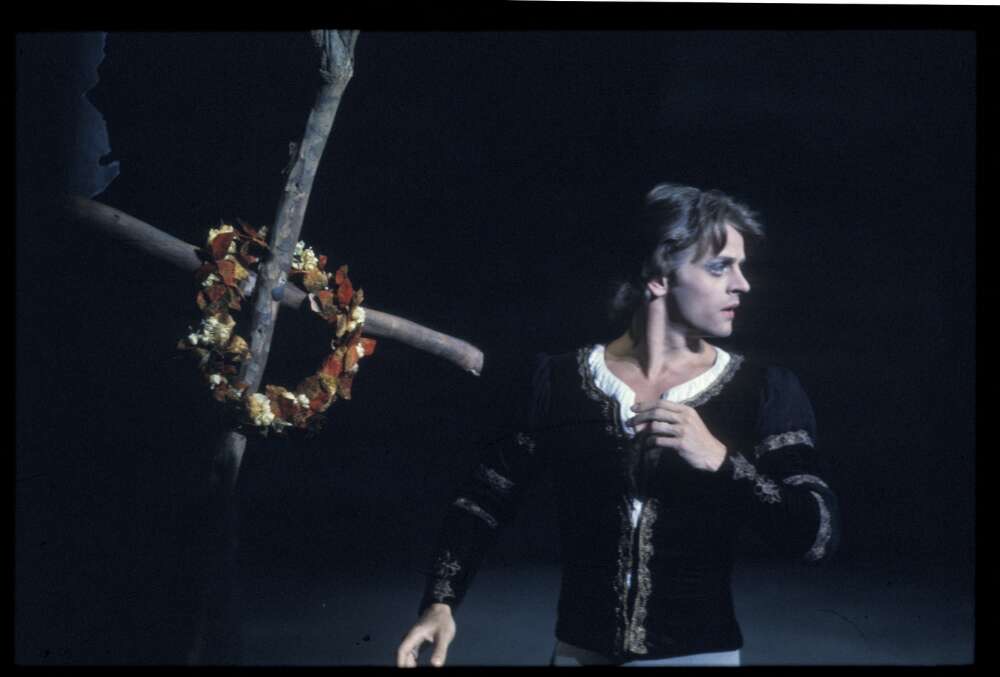

- Stanton Welch on a new Raymonda

I have been thinking recently about Queensland Ballet’s repertoire of ‘reimagined’ narratives for well known ballets—Greg Horsman’s La Bayadère and Coppélia for example. So I was interested to discover that Stanton Welch, Australian artistic director of Houston Ballet since 2003, has just created a new version of Raymonda. It opened on 29 May and the YouTube link below features Welch talking about creating this work.

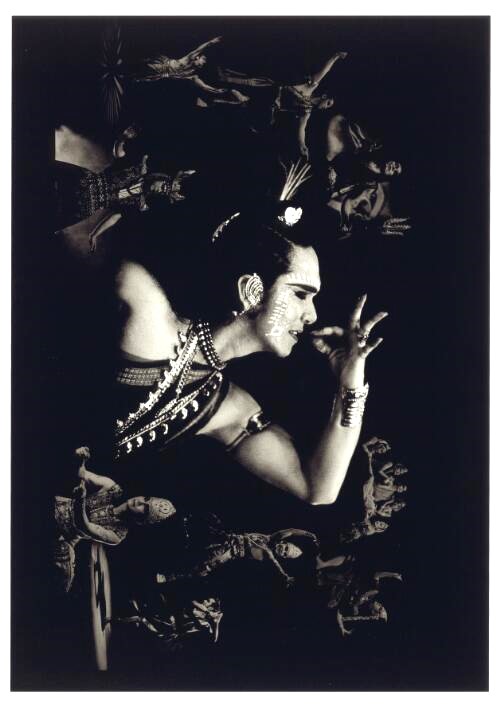

- Chandrabhanu turns 75

Back in 1998 I recorded an oral history interview for the National Library of Australia with dancer Dr Chandrabhanu, whose particular interests were, and still are in Bharata Natyam, Odissi and contemporary dance. That interview is available for research purposes but any public use of it requires written permission. A summary of the contents of the interview can, however, be seen at this link.

Well Dr Chandrabhanu is turning 75 this year and his latest production, Bharata Natyam Reprise, will celebrate that personal milestone with a revival in Melbourne in early June of classical and contemporary compositions of the Bharatam Dance Company. See this link for further details.

- Press for May 2025

– ‘Multi-media novelty item that was sometimes over the top.’ Review of A Book of Hours, Rubiks Collective. CBR City News, 4 May 2025. Online at this link.

Michelle Potter, 31 May 2025

Featured image: Media image for Illume, Bangarra Dance Theatre, 2025. Photo: © Daniel Boud