- Queensland Ballet. The news is out

Queensland Ballet has announced that its new director, following the retirement of Li Cunxin and the sudden departure of Leanne Benjamin, will be Spanish-born Ivan Gil-Ortega who will take on the role in February this year. Gil-Ortega is a celebrated ballet professional with over 25 years in the field. He has held roles with companies and creatives around the world, and has worked as a principal dancer, assistant director, artistic consultant, freelance rehearsal director, stager, and coach. The media release noted Queensland Ballet’s enthusiasm for the appointment. In part the media release says:

We are thrilled to welcome Ivan to the Queensland Ballet family following a stellar career on stage, in studio and working alongside some of ballet’s leading lights. Throughout the recruitment process, Ivan articulated his vision very clearly with a particular focus on our dancers of today and our dancers of tomorrow, through the work of our Academy.

He is also brimming with ideas around nurturing home-grown talent here in Australia as well as exploring world-stage collaborations and exchanges which will see him leaning into his international peers and networks. Ivan and his family are very much looking forward to calling Queensland home and we cannot wait to see them here very soon, Brett Clark AM, Board Chair said.

Gil-Ortega has worked with Queensland Ballet previously when he assisted Derek Deane on the production of Deane’s much admired Strictly Gershwin. Follow this link to a fuller biography of Gil-Ortega provided by Queensland Ballet.

- News from Paul Knobloch

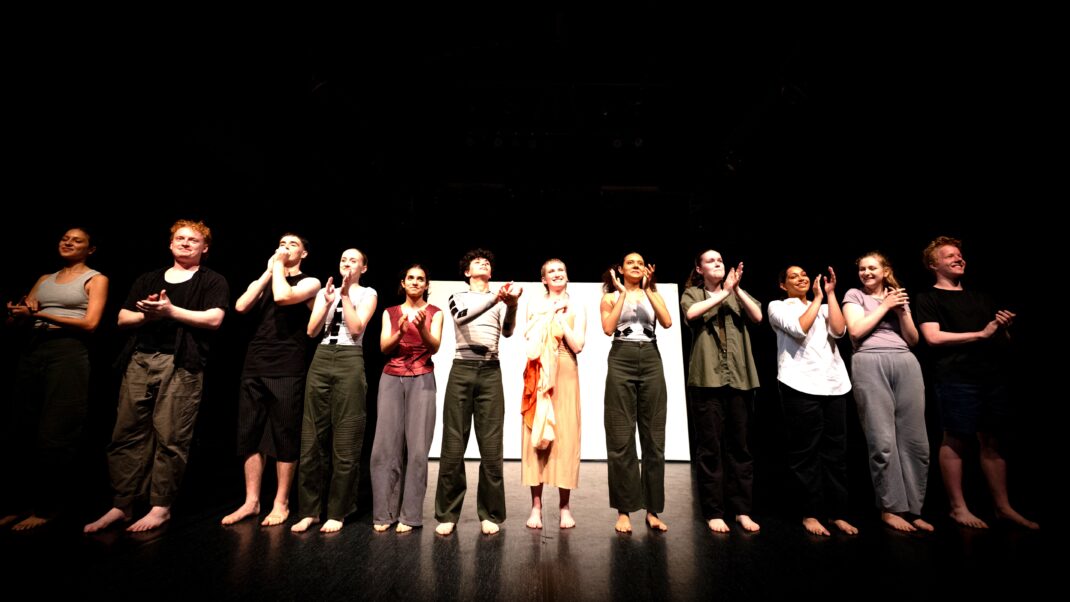

For the past several years Paul Knobloch has been the Australian Ballet’s Ballet Repetiteur. Things appear to be changing, however. A recent media release announced that in February Knobloch will be returning to Canberra, where he was born and educated and where he had his initial dance training. He will be working with Jackie Hallahan’s Dance Development Centre (DDC) on a series of events to celebrate the school’s 40th anniversary. The media release states, ‘As DDC gears up to celebrate its monumental 40th anniversary, Knobloch’s involvement promises to elevate the festivities and inspire the next generation of dancers.’

I can’t help wondering, however, whether or not Knobloch will return to the Australian Ballet? Here is a link to the media release.

- Dancing and Fatboy Slim

During January I was sent a Youtube link to some dancing being performed (back in the 1990s) to Fatboy Slim’s song Praise you. I have to admit that I had never heard of Fatboy Slim—not really part of my general interests I’m afraid especially not during the 1990s when I was rather busy with various other matters (mainly watching children growing into adults, writing a PhD thesis, and working in a range of casual jobs).

Here is the footage, which I found to be an interesting variety of community dance. It reminded me a little of an unexpected performance at a wedding of one of my sons (back around the same date as the footage). Quite out of the blue (I thought anyway) the guests assembled and danced in a similar fashion. It was somewhat different from the traditional celebratory wedding waltz!

- Oral histories

I had the immense pleasure in January of recording an oral history for the National Library of Australia with Megan Connelly, currently director of the Australian Ballet School. As part of the NLA’s COVID responses project, Connelly talked about managing the pandemic at the Australia Ballet and the Australian Ballet School before talking at length about her extraordinary dance career to date.

This interview was the 169th oral history I have recorded for various organisations (mostly the National Library). Here is a link to the updated list of those interviews (arranged alphabetically).

- Reading in December

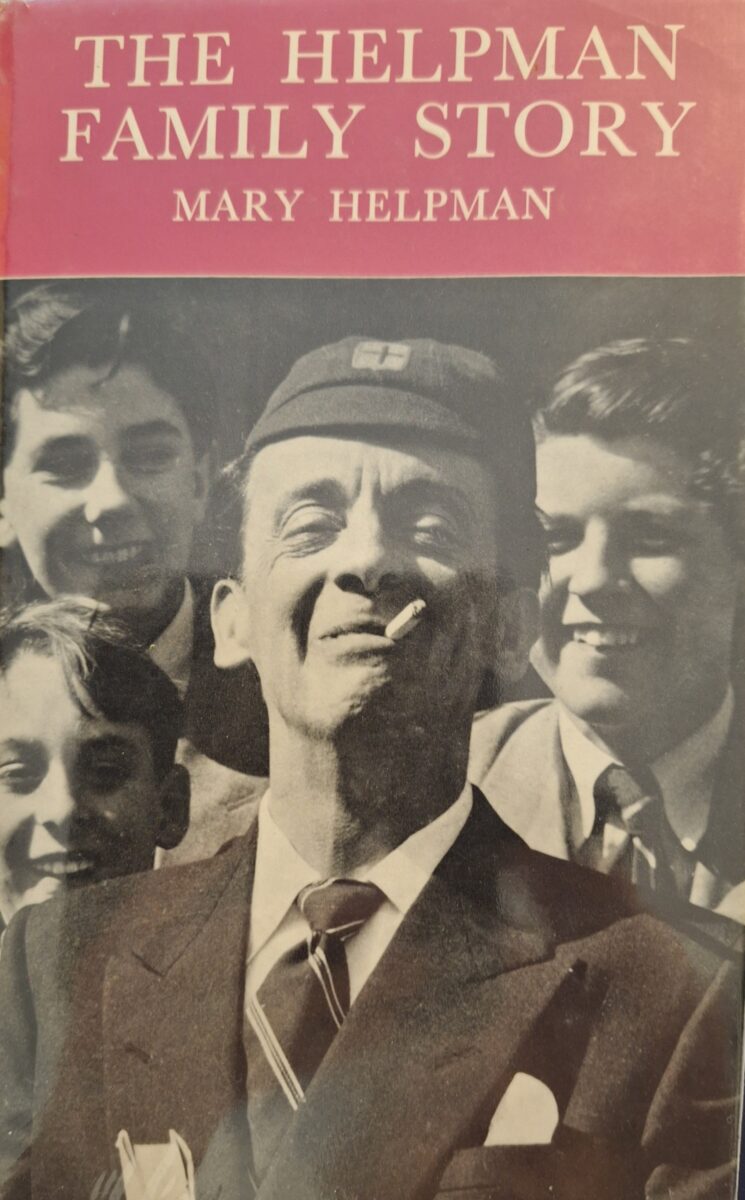

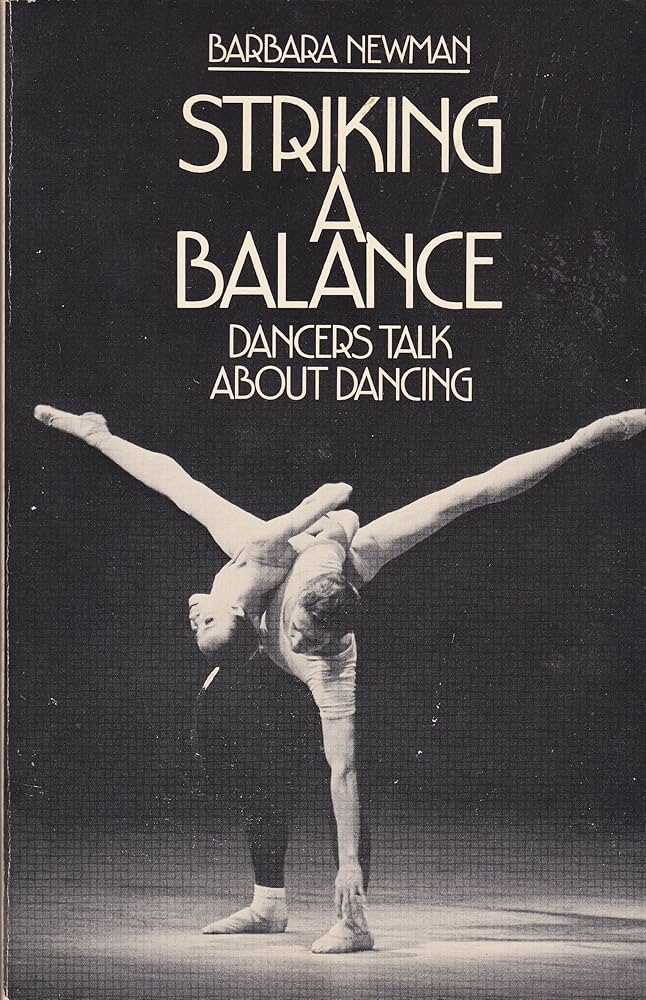

My December reading included Barbara Newman’s Striking a Balance. Dancers Talk about Dancing. My edition was published way back in 1992, although the talks were recorded mostly in 1979 and published in the original edition in 1982. I was especially interested in the format since over the past several decades I have recorded oral history interviews with dancers, choreographers and artistic directors. Two of Newman’s essays stood out for me—those with Moira Shearer and Bruce Marks. What made them especially interesting to me was the extensive comments they made about how they approached particular roles. Shearer spoke at length about how she perceived the character of Giselle and where she fitted into the overall storyline of Giselle. Bruce Marks spoke in a similar fashion about Siegfried in Swan Lake. Others also reminisced about particular roles they had taken on but Shearer and Marks seemed, to me at least, to be especially analytical in their thoughts.

- Vale Carolyn Brown (1927 –2025)

I was deeply saddened to hear that American dancer Carolyn Brown had died in January at the age of 97. Brown had a truly remarkable career with Merce Cunningham Dance Company over many years. But I remember her in particular because she helped me with my doctoral thesis, which concerned the designs made for the Cunningham company by Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns during the 1960s and 1970s. We met for the discussion in New York in a cafe close to Lincoln Center Plaza. Brown was incredibly generous and honest in her recollections of the years of Rauschenberg and Johns.

Never forgotten for many reasons. Try this link for an obituary from The New York Times.

Carolyn Brown: Born 26 September 1927; died 7 January 2025

- Press for January 2025

– ‘Critics Survey. Michelle Potter’. Dance Australia, January/February/March 2025, pp. 32-33.

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2025

Featured image: Portrait of Ivan Gil-Ortega. Photo: © Karine Grace