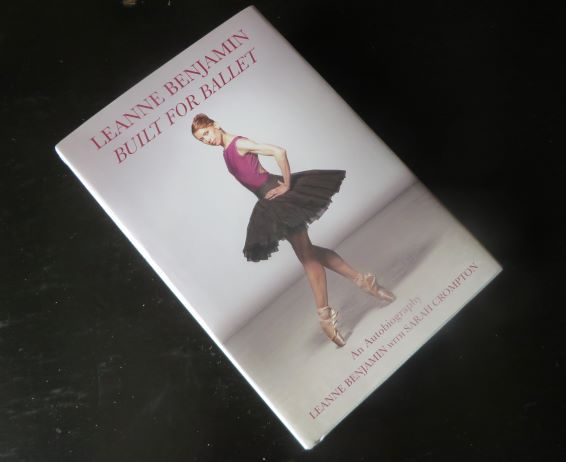

Last time I wrote a book review for this site I was puzzled by the difference between a memoir and an autobiography. Well there is no struggle this time. Leanne Benjamin’s Built for Ballet is clearly an autobiography of a woman who has had an absolutely stellar career as a dancer across continents. It focuses not on one aspect of her life but, going back to where earlier I went searching for definitions, it ‘primarily focuses on facts—the who-what-when-where-why-how of [an author’s] entire timeline.’ We are privy to Benjamin’s dance-focused life from the time she took her first dance lessons, aged three, in Rockhampton, to 2020 when the book was completed. And it is a fascinating account of that life, written in a very conversational tone. It is hard to put the book down once one starts.

I am, however, curious about that conversational tone. While it is lovely to be carried along with the story, I couldn’t help wondering how it was written. Was it partly constructed as a result of oral interviews, with Benjamin’s words translated straight to written form? This would perhaps account for certain grammatical issues that I found a little grating. Speaking isn’t always grammatically correct, especially when agreements between verb and subject, and the use of ‘me’ and ‘I’ as subject or object are concerned. I am perhaps a pedant but I do find certain things annoying and wish that strict copy editing could remain an essential part of book production so that the written word retains its grammatical structure.

Moving on, however, Benjamin is thoroughly honest about her relationships with coaches, directors, other dancers and the like and it is great to read of her approaches to rehearsals, classes, being coached, partners, and performing. Then, one can vicariously feel the exhaustion of the extensive travel that Benjamin undertook both with the companies with which she was involved and as a guest artist around the world. The way Benjamin addresses the various injuries all dancers sustain over the course of a career also arouses a feeling of empathy for the pain and the loss of performances that have to be endured.

I especially enjoyed Benjamin’s discussion of her work with some of the most outstanding choreographers of her time. Her work with Kenneth MacMillan, and later with Wayne McGregor, stand out. What did she gain from being coached by them? And how was she able to pass on what she had gained to younger dancers when she became a coach herself? It’s all there. And yes, her thoughts on Ross Stretton and his time both with the Australian Ballet and the Royal Ballet are featured at one stage.

Benjamin does not gloss over her personal life either. We learn of her various love interests, her marriage and the birth of her son, and the fate of her extended family including her mother-in-law and father-in-law, both of whom had major dance or dance-related careers.

Perhaps one section that I found fascinating, largely because of where I live, concerned the photo that appears on the back cover of the book (although all the photos in the book are interesting and often quite personal). The back cover has a photograph taken in 2006 by Jason Bell at a location outside Alice Springs. It is a spectacular image. A print is in the collection of the National Library of Australia in Canberra and is often used as a publicity shot for anything to do with dance and the National Library. It is etched in my mind as a result. Benjamin discusses the circumstances surrounding the photo shoot.

Built for Ballet is an engrossing read. It is honest to the core and opens one’s eyes to much that goes on behind the scenes in a dancer’s life. Built for Ballet is published by Melbourne Books.

Michelle Potter, 8 November 2021