As I write this month’s dance diary, Australia is in the middle of National Reconciliation Week and today is a public holiday in the ACT. National Reconciliation Week is a reflective time to explore shared histories, cultures, and achievements, and to examine ways in which reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians might be achieved. It seems appropriate then to begin this month’s dance diary with news from two Indigenous dance companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre and Marrugeku.

- Bangarra’s new program for children

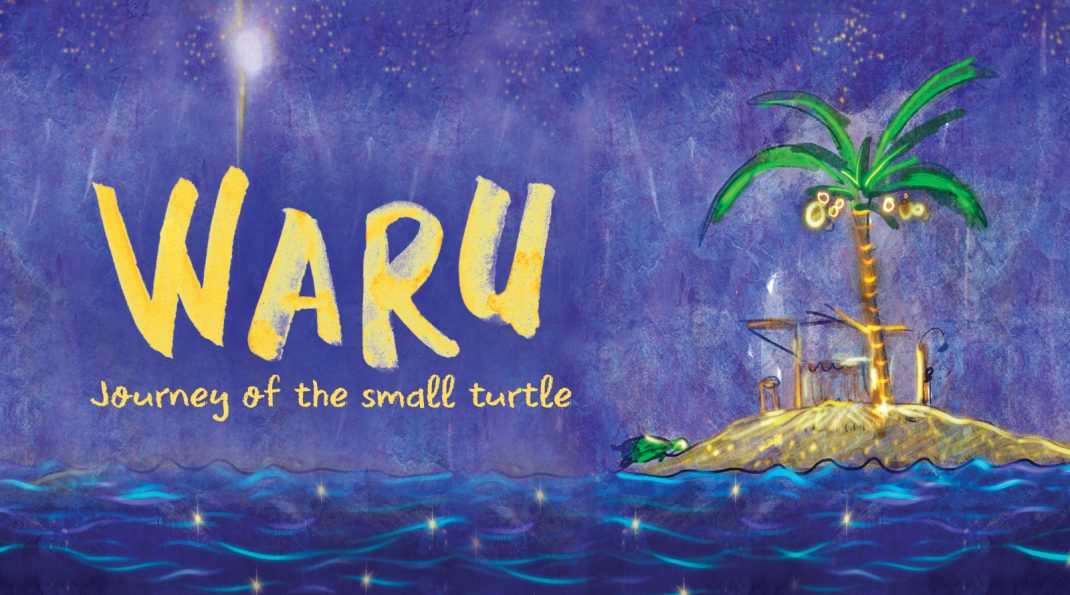

Bangarra Dance Theatre has announced a new initiative, a work for children called Waru—journey of the small turtle. Conceived and created by Stephen Page and Hunter Page-Lochard, along with former Bangarra dancers and choreographers Sani Townson and Elma Kris, it tells the story of Migi the turtle who navigates her way back to the island where she was born. Waru is for children aged between three and seven years old and will have its official premiere performance later in 2021. A preview season is due to take place in Bangarra’s newly renovated home at Walsh Bay, from 7-10 July. More about the official premiere as it comes to hand.

- A new work from Marrugeku

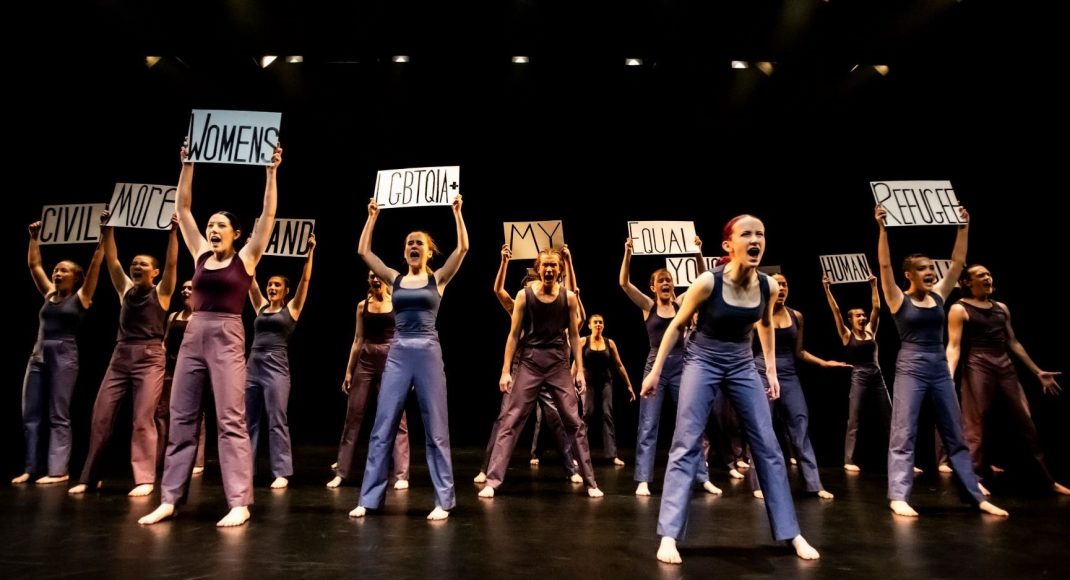

In another initiative, the Broome-based company Marrugeku, which is also company in residence at Sydney’s Carriageworks, will present Jurrungu Ngan-ga (Straight Talk) at Carriageworks between 4 and 7 August 2021. This work, based on a concept by Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain with input from Patrick Dodson, reflects on life inside Australian immigration and detention centres. More information from Carriageworks.

- Another award for David McAllister

Like so many recently scheduled arts events, the annual Helpmann Awards were cancelled this year. Nevertheless, early in May 2021 the organising committee awarded two Industry Achievement Awards for 2020. These awards recognise an individual who has made an exceptional contribution to the Australian live performance industry and one went to recently retired artistic director of the Australian Ballet, David McAllister. It added to his Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Award, which he received in April.

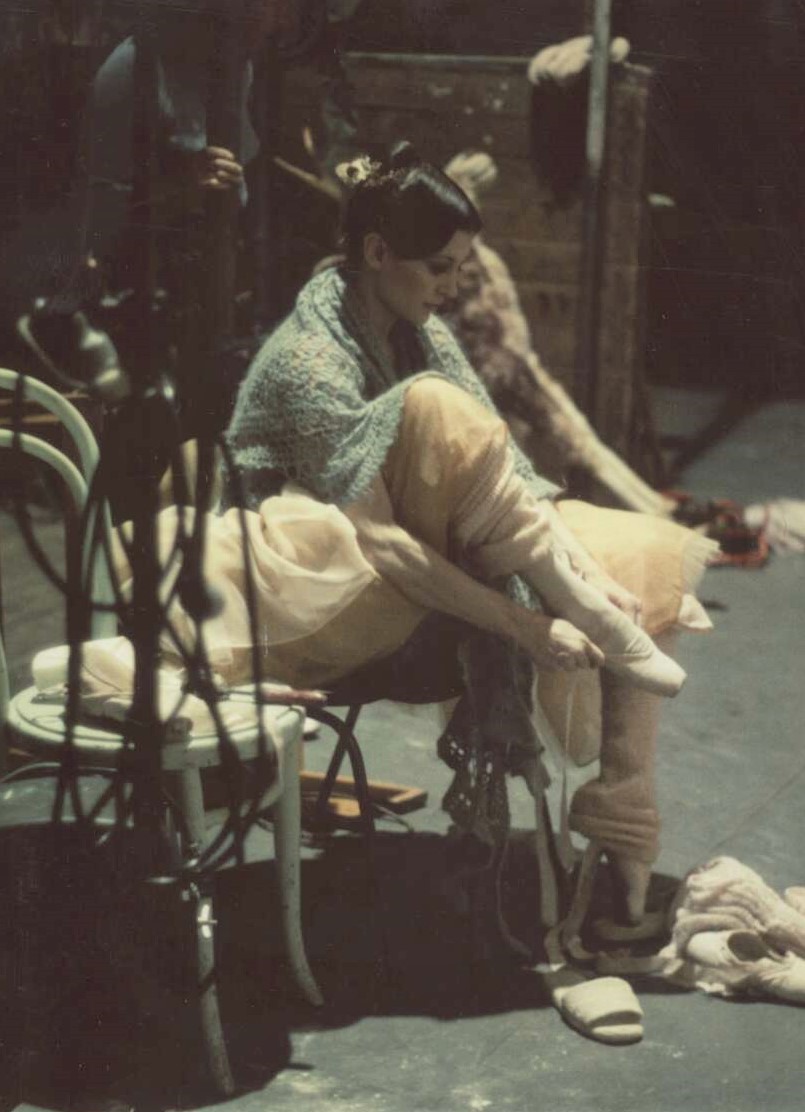

- Carla Fracci (1936-2021)

Famed Italian ballerina Carla Fracci has died in Milan aged 84. Fracci’s illustrious career included guest performances in Australia in 1976 when she danced Giselle to Kelvin Coe’s Albrecht. An obituary is at this link.

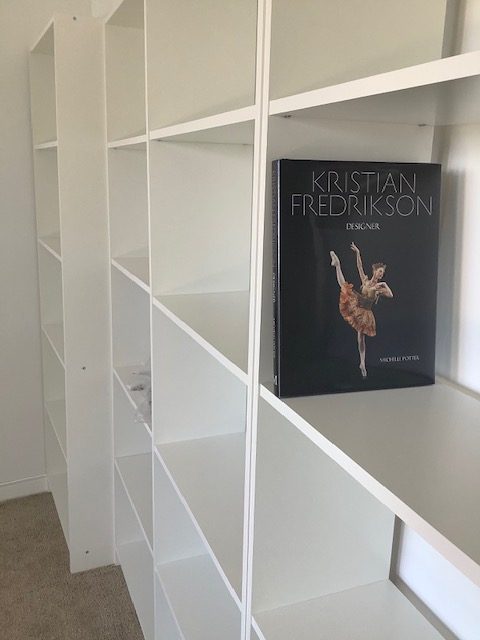

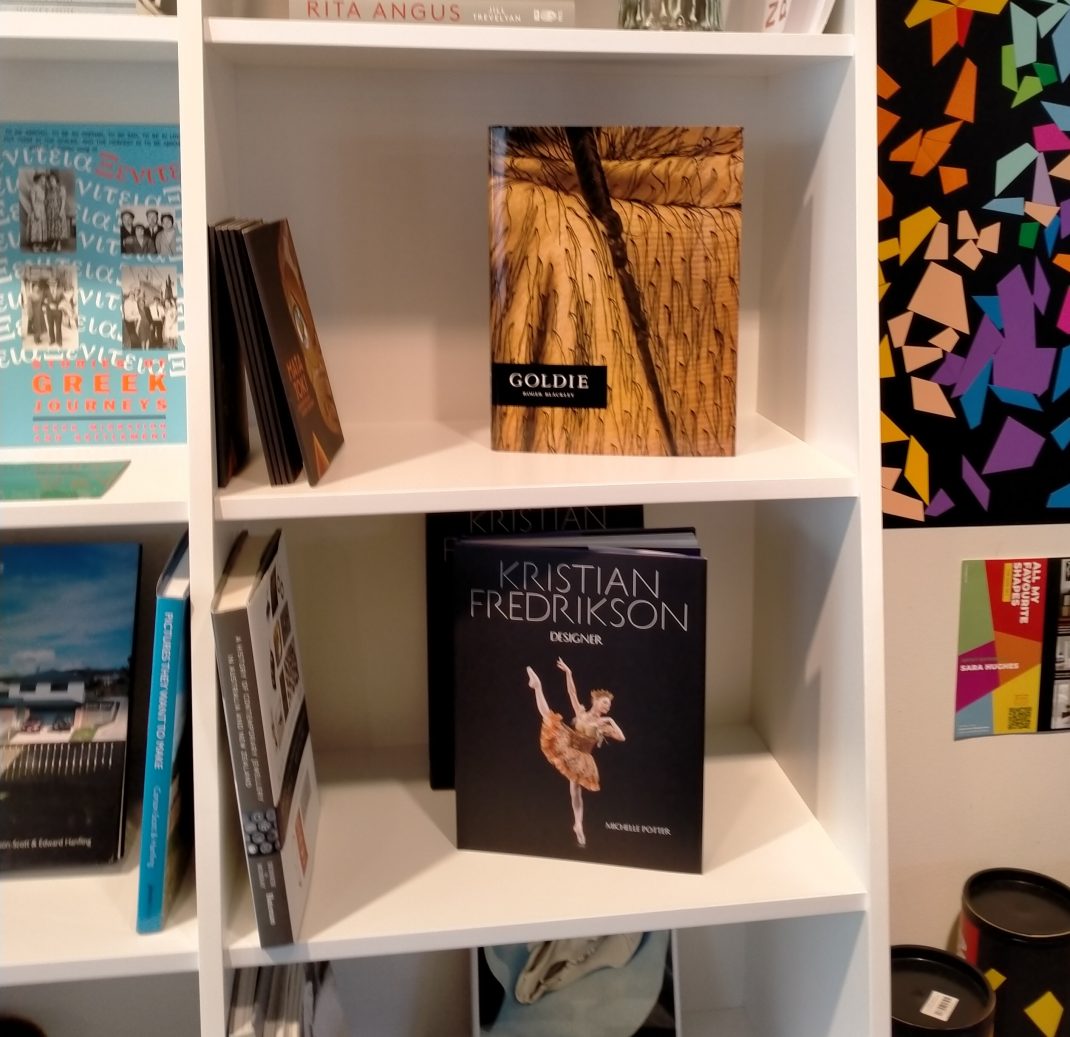

- Kristian Fredrikson. Designer

After a year since publication, reviews of the Kristian Fredrikson book have pretty much come to an end. I can’t resist sharing, however, the images below.

On the left is the book taking ‘pride of place’ in the new, yet to be completed home office of a distinguished professor of art and design. On the right is the display at the Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, New Zealand.

- Press for May 2021

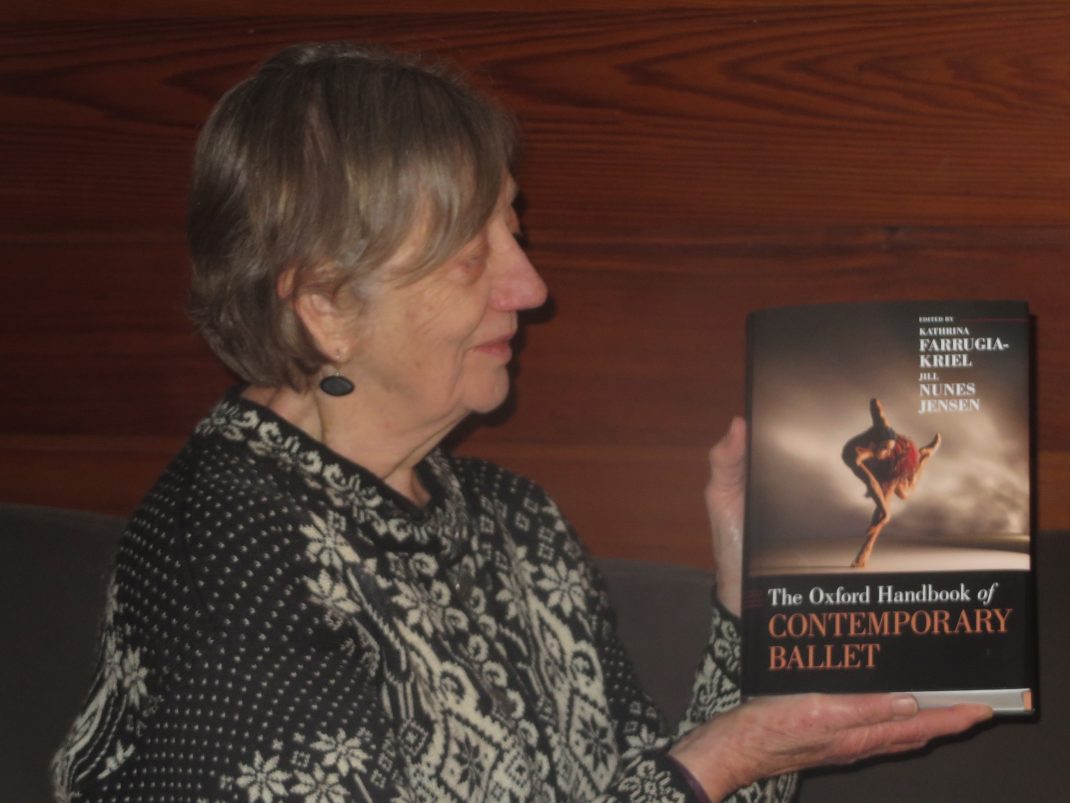

‘New narratives from old texts: contemporary ballet in Australia’ in The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet. Edited by Jill Nunes Jensen and Kathrina Farrugia-Kriel (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021) pp. 179-194.

My copy of the Oxford Handbook finally arrived and it is certainly a handsome publication. Apart from the impressive scope of the articles, it is well edited and shows exceptional respect for those involved in its production. All the photographers are acknowledged by name in the ‘Acknowledgments’ section, for example. That kind of acknowledgment doesn’t happen very often

A list of the chapters in this 982 page tome is at the very end of Dance diary. January 2021.

Michelle Potter, 31 May 2021

Featured image: Design image for Waru—journey of the small turtle.

Design: © Jacob Nash, 2021