Dancer, visual artist, choreographer and writer Eileen Kramer has died in Sydney at the age of 110. Born in Sydney, Eileen spent her early years in the suburb of Mosman and then, after her parents’ divorce, in Coogee. After leaving school at the early age of 13, she eventually began studying singing, piano and theory at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music but did not take up dancing until she was in her twenties when she saw a performance of The Blue Danube and other works from the Bodenwieser Ballet. Of that experience she has said:

Well, Blue Danube is beautiful and flowing and expressive and not at all tight and rigid, so I just fell in love with it. Another dance they performed at that concert was the Slavonic, those great big skirts with big motifs on them, and that struck me because when they came onto the floor they took wonderful poses that looked as though they were accidental. But of course it was art, so I went immediately to become a student.

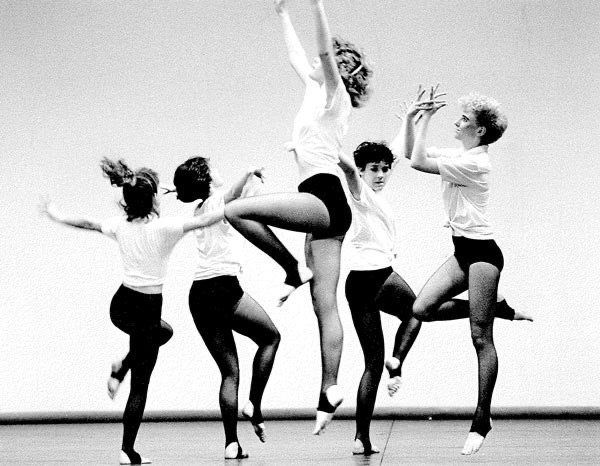

She was accepted as a student by Gertrud Bodenwieser and later became a company dancer touring with the troupe around Australia and overseas for the next decade. Of her time with Bodenwieser she recorded:

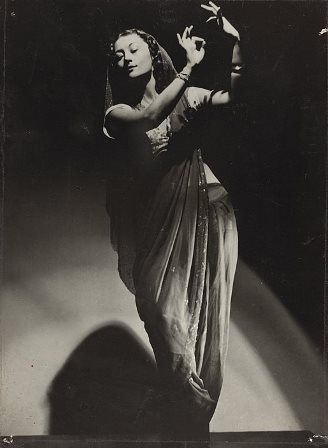

Well, to us [Bodenwieser] was exotic and wonderful and we felt she was teaching us not only dance but about European culture and sophistication as well. And she also recognised each one’s quality. So while we learned to work as a group, she also developed our qualities, which was quite wonderful. So then she’d give solo dances inspired by us, not something that she got from somewhere else. My dance that I loved most of all was Indian Love Song. I wasn’t doing a traditional Indian movement but it was inspired by Indian poetry and some Indian postures, but I had to sing the song with that.

For Bodenwieser, and for the rest of her life, Eileen was a designer of costumes. Speaking of her interest in design she said:

I didn’t make so many drawings and that upset Madame a little bit, because she liked to see what she was getting, but I worked in a way of giving more freedom to the fabric so I would make it on the figure and not so much from drawings, although generally you had to have an idea of what you were doing and make a kind of a sketch, but not a detailed sketch. I have been doing this since I was about five years old, making dolls’ clothes and then eventually making my own clothes and making backyard concert clothes.

After leaving the Bodenwieser Ballet she lived and worked in India, France and the United States for the next 60 years. Those years included relationships of various kinds including with her husband Baruch Shadmi, whom she met in Paris. They collaborated on a number of activities but he suffered a stroke and she gave up her career to nurse him until his death.

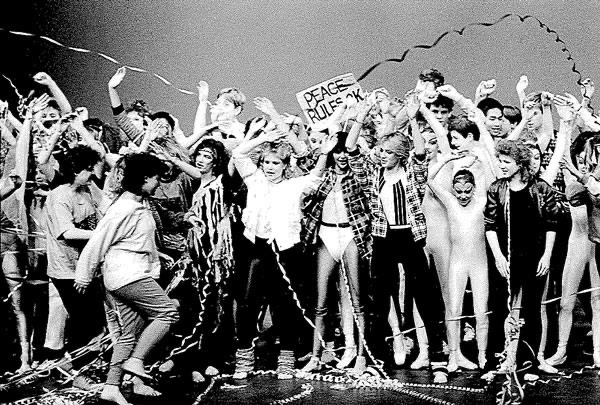

On her departure from Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where she had spent the last several years of her career the local newspaper wrote:

A crowd of costumed friends gave one of Lewisburg’s most colorful residents, Eileen Kramer, a wonderful send-off at the Greenbrier Valley Airport Wednesday afternoon upon her departure for Australia. Garbed in attire designed and sewn by Eileen from Trillium performances over the years, and bearing large masks she’d painted, the gathering lovingly gave tribute to say “Thank you” and “We love you” and “We will miss you.’ Fare thee well, Lovely Lady Mountain Messenger, Lewisberg, 9 September 2013 https://mountainmessenger.com/fare-thee-well-lovely-lady-2/

Eileen lived in Sydney from 2013 until her death. In those last 11 years she continued to create. Her activities are recalled on her website, Eileen Kramer. Of the many activities in which she was involved during those last years, perhaps my favourite is the beautiful film by Sue Healey made for the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, available at this link. See also my thoughts on the film here.

Vale Eileen. How lucky I was to meet you when and how I did. When we spoke last you recalled the oral history we did—now more than 20 years ago. You remembered that we lunched in between sessions. You said that no other interviewer had done that! Well I loved that I was able to do so.

Eileen Kramer: born Sydney, 8 November 1914; died Sydney, 15 November 2024

Michelle Potter, 17 November 2024

For other posts about Eileen on this website, follow this tag.

Unless otherwise identified, quotes from Eileen in this post are from an oral history I recorded with her in 2003 for the National Library of Australia, TRC 4923, available online at this link. Eileen’s autobiography, Walkabout Dancer was published in 2008 by Trafford Publishing.

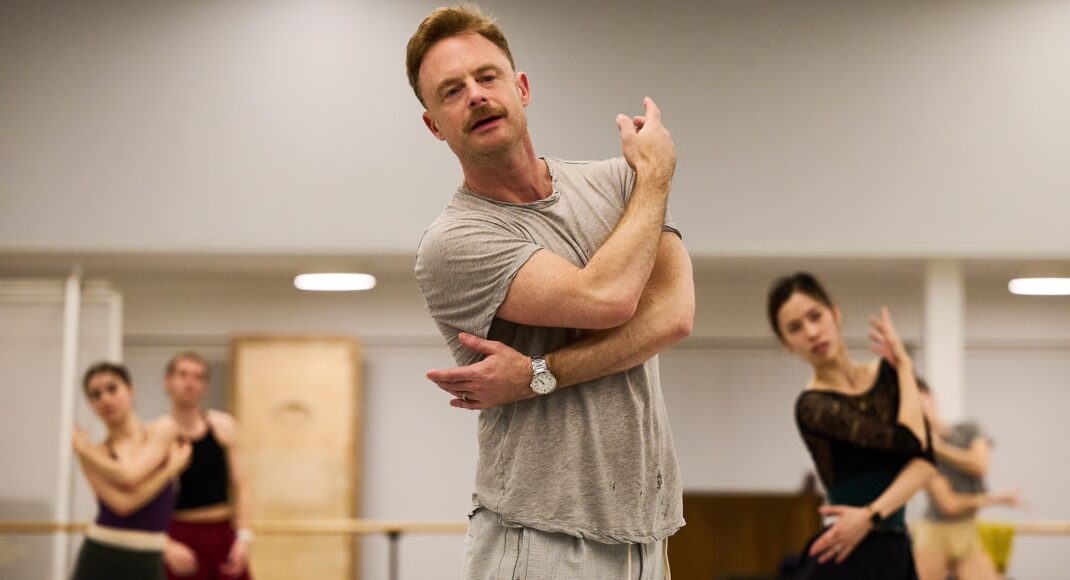

Featured image: From Sue Healey’s film Eileen, 2017. See this link to view the film.

Update: When I first posted this obituary I added an image that was purported to be of Eileen as a baby along with her father and mother. Well, when I looked through Walkabout Dancer, the autobiography, it turned out that it wasn’t Eileen as a baby but Edward (her brother). I am assuming Eileen knew who it was and that the source I used got it wrong! So I have removed the image from the post proper but have included it below. The photographer has not been identified but the date would be 1913.