2 July 2023. Lower Hutt Little Theatre

Choreography: Vivek Kinra

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Darpana is a retrospective program of excerpts from the past three decades of seasons choreographed by Vivek Kinra for his company, Mudra. It’s a garden of earthly delights with celestial resonance, story-telling laced with joyous cavorting. There are sudden flashes of fury whenever forces of evil are encountered. Furious stamping, piercing glares and dismissive gestures will rid us of them. Only the good survive, only the safe are free.

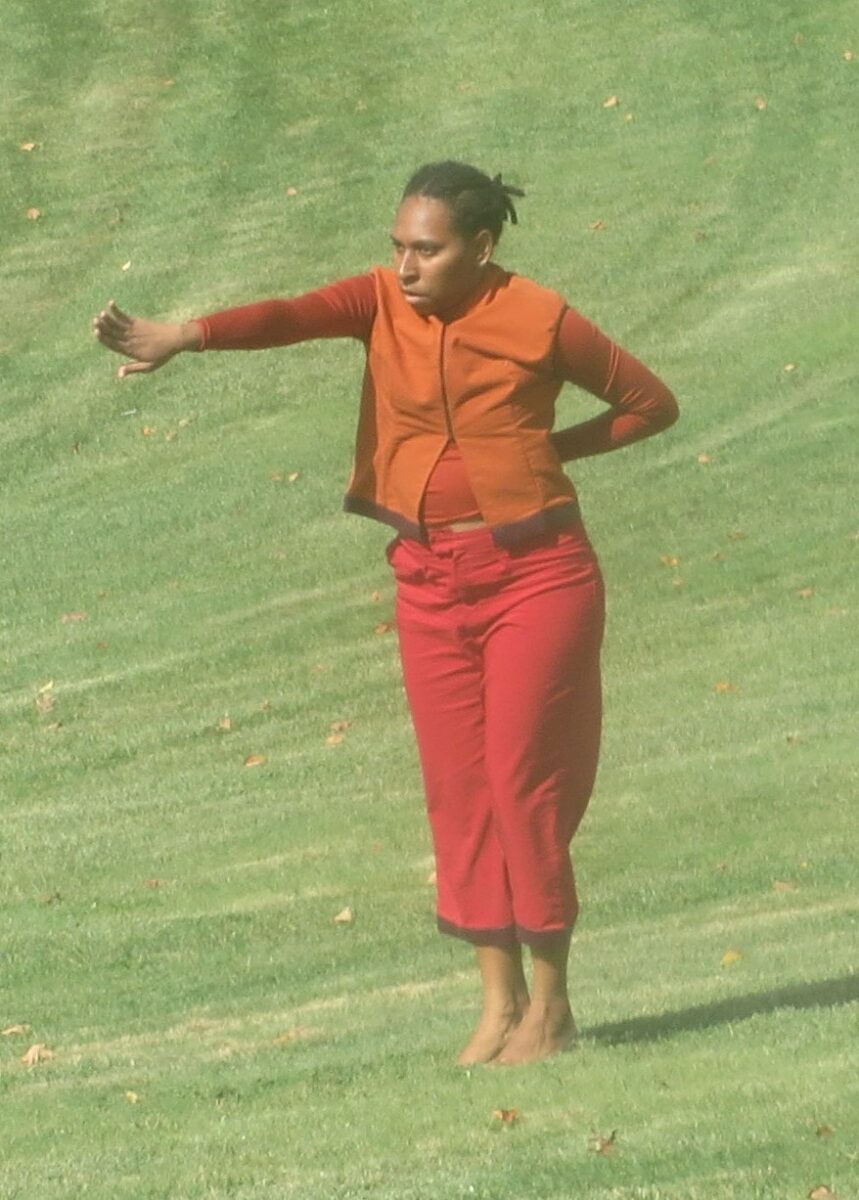

This vividly expressive form of Indian dance, Bharata Natyam, runs the gamut of human emotions and motives, portraying figures from the parallel realm of deities whose examples are to be followed. It’s an art form in which singing, instrumental music (mridangam drum, violin, flute) and visual rhythm (dance)—in dramatic, poetic, and abstract patterned aspects—all find equal share in the performers’ finely-tuned detail and precise geometry of the body. And then there’s the dress-ups, further feast for the eyes, with carefully gradated lighting effects from full colour to serene silhouettes, from dawn to day to dusk.

After weeks of balmy mid-winter weather, the afternoon suddenly drops 10o, feels like zero, and icy rain drenches us on the way to the theatre. Never mind, Lower Hutt is closer than India so it’s a small price to pay for the transport of joy awaiting us. Every season of Mudra since the mid 90s has revived memories of my visit to India for dance studies in the previous decade. O India, the country with the world’s richest of dance traditions. Time flies, time stands still, to be here is to be there.

Mudra’s troupe of eight senior performers are all in full flower—joined by 15 junior dancers in bud—(one of them already on the way to stardom, but steady on, no sensible dance teacher wants a prodigy, a meteor that falls and burns out, better a star to last forever. I’ve had my eye on this youngster for 7 or so years now, and she is doing exactly as her teacher and I predicted she would).

Kinra was trained at Kalakshetra, the epicentre of Bharata Natyam teaching, near Chennai. The founder of the school, Rukmini Devi, envisaged a centre of arts and related crafts to thrive alongside community education initiatives. As a theosophist Devi visited New Zealand to connect with the Theosophical Society here, and also devoted time to animal rights’ causes. As a young dancer she had met Anna Pavlova who was touring with her company to India in 1922. Pavlova encouraged Devi in a revitalisation of Bharata Natyam away from the temple, towards the theatre. Her contemporary, Balasaraswati, was the legendary dancer who toured the world’s capitals and showed what heights a solo performer could reach, even towards the age of 70. They say Martha Graham sat in the audience and wept, and she was not alone. (If you don’t believe me, watch Bala, the film about her made by Satyajit Ray. It’s on Youtube). A century later, many cities of the world offer training in Bharata Natyam India’s gift to the world—which takes on intriguing differences depending on each locale.

Kinra’s students are drawn from all the states of India, whether born there and migrated here, or born here. Others are of Sri Lankan or Malaysian Tamil, or maybe Fiji-Indian descent. But wait, there’s a Pakeha of Anglo/Irish line among them—though you only know that from the program note, her dancing is up there with the best of the rest.

Read the BBC news item from a few days ago, a lengthy and fascinating report of the ancient and mysterious folk ritual, Theyyam practised in Kerala—where members of Dalit, the lowest caste, perform in an ancient dance-drama. High caste members are required to attend and revere them. Think about that.

Here with Mudra we watch the daughters of Brahmin neurosurgeons or scientists (so long as under-resourcing of health or academic budgets has not closed down their work places) or of the local corner dairy (so long as ram raiders or armed invaders have not knifed them to death). Many of these dancers hold professional careers in law, education, science, technology, commerce—yet their radiant performances would have you believe they are full-time professional artists.

Each of the nine works is choreographed from the subtle tension between tradition and individual dancers’ personalities, all of whom deserve praise. One dancer leaps high and sideways, lands in ‘first position’ on the half foot, slowly continues down to a deep full plie, leans sideways then slips onto her knee and hip while sliding over the floor, then she comes back into the vertical and slowly returns to standing, all the while smiling. (Don’t try this at home. Well, the smile maybe, but for the rest you’ll need to be in training for years).

Varshini Suresh makes a stunning position flow to the next with great grace and it’s hard to take your eyes off that as she invests her dancing with expressive joy. Banu Siva has a wonderful poetic and rhythmic clarity in every aspect of her movement. Shrinidhi Bharadwaj is the dramatic force who propels the power of story-telling to great effect. The treasured Zeenat Vintiner is most welcome back as she rejoins Mudra after several years break. Her personal life reads like something from the Mahabharata, and echoes the story of the Polish refugee children who were given haven in New Zealand 80 years ago. Her own experience is a triumph for her, her family and her teacher.

My grandchildren were agog at the stamina demanded of these performers—loved the contrasting qualities between them—and were greatly taken with the calm way the dancers managed the tiniest little ‘things’ that happened: a tiny bell from an anklet falls off onto the stage—we can see it glinting and hope that the other dancers can too because you would not want to leap and land on that piece of metal. One dancer’s long black braid plaited with flowers comes loose from the belt which holds it in place as she twirls at speed. With great aplomb she continues dancing but ensures by various miniature twists that it not fly out and hit her fellow dancer in the face. (This is like a pilot realising that one engine is malfunctioning. Nought to do but keep calm, switch it off and use the other engine to make a faultless landing). Another dancer leaps high into a very narrow space between two others and knows her foot might catch in the swathe of silk that she’s wearing—so mid-air she leaps even higher and ever so slightly changes course. Stunning. My grandkids say ‘We love watching how these little things are managed—it makes the dancers seem more human and a little bit like all of us.’

They are equally pleased by the refreshments at intermission — the best samosa and ladoo in town—and a program note that the catering is by Awhina, the impressive New Zealand enterprise that fundraises to help women widowed by war in Sri Lanka, in a range of small scale development projects. I thank the young woman for my spicy masala tea, tell her how well the performance is going and hope she gets to glimpse some of it herself. ‘Oh I was dancing in last night’s cast—I’m just helping out front tonight.’ she smiles.

Poul Gnatt founded our New Zealand Ballet on ingenuity like that, 70 years ago. He’d have loved this performance as much as I did.

Jennifer Shennan, 4 July 2023

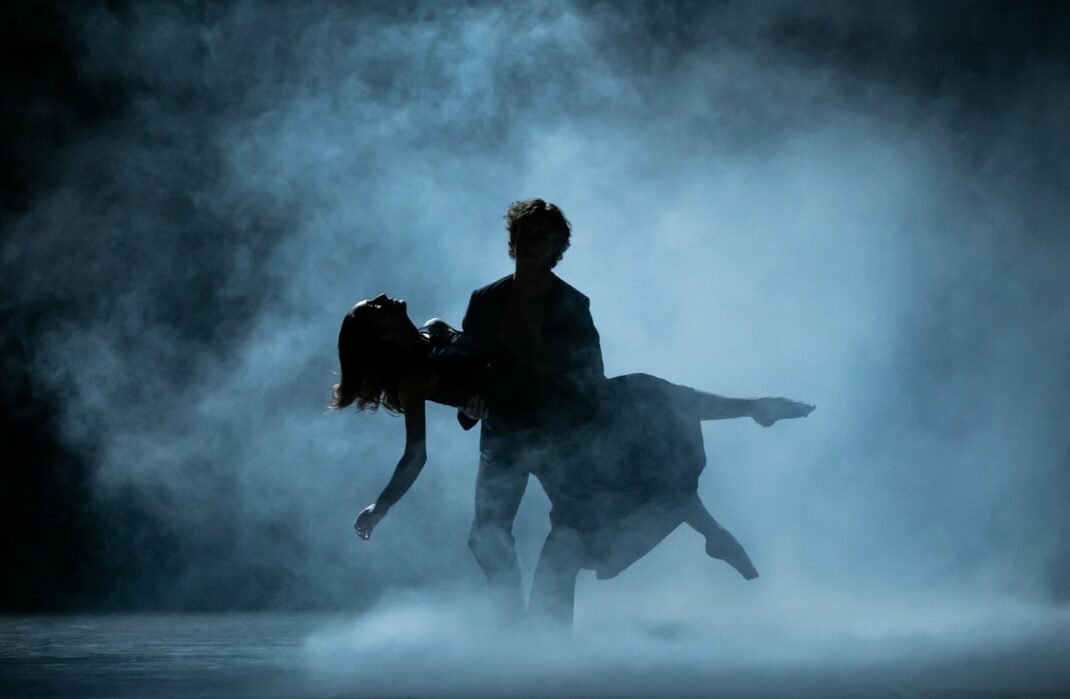

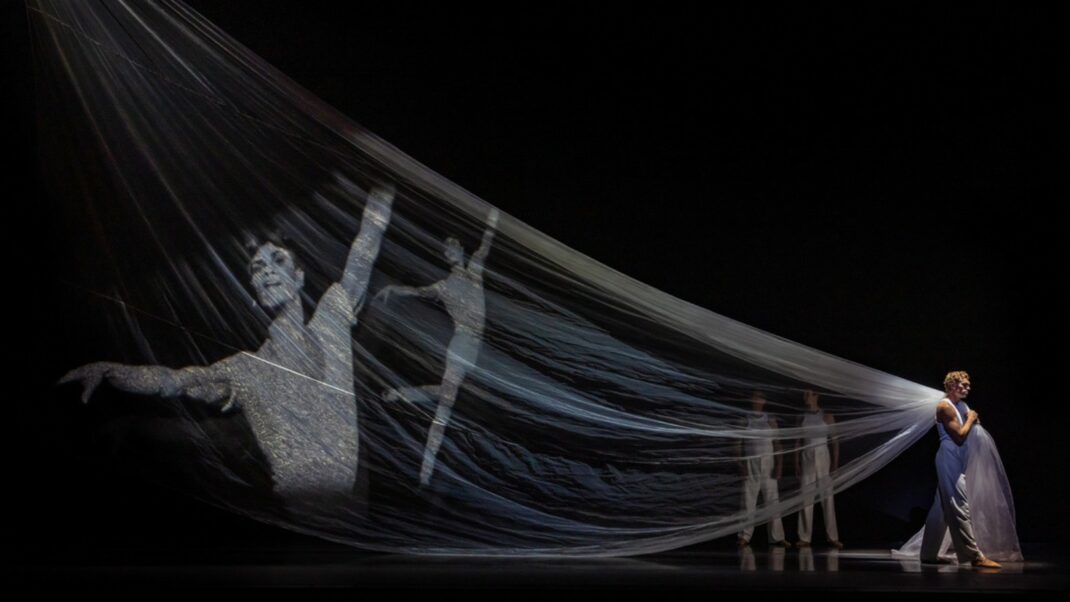

Featured image: Abiraami Antony-Pillai (left) and Anika Mair in a moment from Darpana Reflections, Mudra Dance Company 2023. Photo: © Gerry Keating