Laurel Martyn, one of Australia’s most eminent dancers, choreographers and dance educators, has died in Melbourne on 16 October, three years short of her 100th birthday. Born in Toowoomba, Queensland, as Laurel Gill, Martyn received her early dance training with Kathleen Hamilton in Toowoomba and Marjorie Hollinshed in Brisbane and in 1933 left Australia for further training. In England she studied with Phyllis Bedells and in 1934 won a choreographic scholarship from the Association of Operatic Dancing (later the Royal Academy of Dancing) with her first composition Exile. She passed all her Royal Academy exams to Solo Seal and in 1935 won the Adeline Genée gold medal, the second Australian to do so in the then short life of the competition, which began in 1931. In 1935 Martyn also arranged the dances for a production of The Waltz King and in the same year received second prize in a choreographic competition, the Pavlova Casket, for her ballet Sigrid.

Martyn joined the Vic-Wells Ballet (later Sadler’s Wells Ballet) in 1936. She was the first Australian woman to be accepted into the company and by 1938 was a soloist. While in England she changed her name from Gill to Martyn, also a family name. She danced in many of Frederick Ashton’s early ballets including Horoscope, Nocturne and Le Baiser de la fée and also spent time in Paris studying with the Russian émigré ballerinas Lubov Egorova and Mathilde Kchessinska.

Martyn returned to Australia in 1938 following the death of her father and took up a position in Melbourne with well-known teacher Jennie Brenan. While teaching for Brenan she was offered the dancing lead in Hiawatha, a pageant produced by T. E. Fairbairn and choreographed by Brenan, which opened in Melbourne’s Exhibition Building on 21 October 1939. The ballet cast of 80 was led by Martyn, Serge Bousloff and Lawrence Rentoul. While performing in Hiawatha Martyn was noticed by Edouard Borovansky who persuaded her to join his fledgling Borovansky Ballet, which she did in 1940. Martyn was one of Borovansky’s principal artists in the early days of the Borovansky Ballet, along with Edna Busse and fellow Queenslander Dorothy Stevenson. Martyn danced and created leading roles with Borovansky until 1945, including the Spirit of the River in Borovansky’s meditation on his Czech homeland, Vltava. While with Borovansky she also restaged Sigrid and reworked what is probably her best known work, En Saga, which premiered for the Borovansky Ballet in 1941.

Martyn left the Borovansky Ballet after her marriage to Lloyd Lawton in 1945. But in 1946, at the request of the Melbourne Ballet Club, Martyn took on the directorship of Ballet Guild, as the Melbourne Ballet Club had renamed itself. She was its director for an extended period. Ballet Guild became Victorian Ballet Company in 1963 and Ballet Victoria in 1967. Martyn was at the helm until 1973. She also established a school associated with Ballet Guild and students from the school augmented professional dancers in Ballet Guild productions. Martyn created many original works for Ballet Guild and Ballet Victoria productions and collaborated with Australian composers, including Dorian Le Gallienne, Margaret Sutherland, John Tallis, Esther Rofe, and Verdon Williams, and Australian designers, including Alan McCulloch, Len Annois, and John Sumner. Some of her works also had specifically Australian themes, notably The Sentimental Bloke (1952) and Mathinna (1954). Other significant works that Martyn made in this period included L’Amour enchantée (1950), a full-length Sylvia (1962), Voyageur (1956) and Eve of St Agnes (1966).

Martyn developed a specific method for teaching dance to children, the principles of which she published in Let them Dance (1985). She also was instrumental in forming the Young Dancers’ Theatre, for which she choreographed several works in the 1980s, and the Classical Dance Teachers Australia Inc, which provided in-service training for dance teachers. She was on the steering committee for the Australian Institute of Classical Dance in the early years of its development. Martyn guested with the Australian Ballet as Mar in The Sentimental Bloke in 1985, as the mother of James in La Sylphide also in 1985, as Berthe, Giselle’s mother, in Giselle in 1986 and as Miss Maud in The Competition (Le Concours) in 1989. In 1991 she reproduced Michel Fokine’s Le Carnaval for the flagship company. In 1997 she was the recipient of the award for lifetime achievement at the inaugural Australian Dance Awards.

Martyn was interviewed for the National Library of Australia’s oral history program in 1989 and the interview is available online at this link. See also ‘Inspiring Mentors: Valrene Tweedie and Laurel Martyn’ published in July 2002 in National Library of Australia News. In addition, a special issue of Brolga: an Australian journal about dance—Issue 4 (June 1996)—was published in honour of Martyn’s 80th birthday. It contains the following articles:

- Laurel Martyn OBE: a voyager ahead of her time by Janet Karin

- In her own words: excerpts from an oral history interview with Laurel Martyn

- The choreography of Laurel Martyn, 1935–1991

- The smile of Terpsichore: notes on Laurel Martyn as choreographer by Robin Grove

- Dancing the Bloke by Geoffrey Ingram

- Laurel Martyn and her composers, 1946–1956 by Joel Crotty

Also published in Brolga, in its first issue of December 1994, and under the title ‘Silent stories’, is Robin Grove’s incisive discussion of Martyn’s Sylvia.

Laurel Martin Lawton: born Toowoomba, 23 July 1916; died Melbourne, 16 October 2013.

Michelle Potter, 19 October 2013

*This brief biography draws on original research I carried out, first for the National Film and Sound Archive’s Keep Dancing! project between 1997 and 2001 and then as part of the early stages of the National Library of Australia’s Australia Dancing project beginning in 2002.

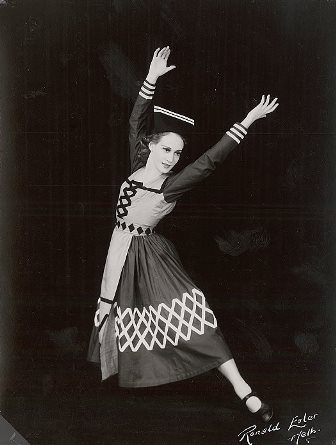

Featured image: Laurel Martyn as Remorse in Fantasy on Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, Borovansky Ballet, 1945. National Library of Australia

I know this is all trivia, but I often find that reading an account of a theatrical artist’s life is like looking at a family tree – so many interesting connections. Fairbairn presented Hiawatha in London at the Royal Albert Hall from 1924 to 1939 – the original costumes and scenery were designed by the eminent Australian artist, Frederick Leist. Phyllis Bedells danced the leading female role, later taken by Martyn, for six or seven seasons. Borovansky takes us to Pavlova; Egorova and Kschessinska to the Imperial Theatre; Serge Bousloff to de Basil; Marjorie Hollinshed to Laurent Novikoff. And Martyn herself even takes us to early television broadcasts – she appeared in the 1937 BBC broadcast of Swan Lake with Fonteyn and Helpmann.

David, you are absolutely right about the links between artists. I am especially interested in your comments on the London version of Hiawatha too – more to do there from this end of the world.

Both my mother and grandmother loved ballet and took me to performances as soon as I was old enough. I have such rich memories of going to the ballet with my grandmother, what a treat . And just by the way I was named after Laurel Martyn my mother’s favourite dancer. I am sure I am not the only one to have been named after this remarkable ballerina.

Thank you for sharing your story. How lovely to be named after Laurel Martyn. As it happens it is my mother’s name too.

I attended a performance of Hiawatha when I was very young. I remember the massed choirs from the suburbs of Melbourne. We knew some singers and sat with Mrs Collett from the Heidelberg choir as she read the score and made native sounds beating her hand against her mouth. At intermission dancers and performers were resting on the slanting boards because of their elaborate costumes. I was googling and saw Laurel Martyn…I worked with Boro but remember Laurel lending her studio where we were waiting all night for tickets for the Old Vic. The room was full of us sleeping on the floor. My first ballet was the deBasil. I was about 6. A lady told me I was lucky to see Lifar dancing at a matinee. My first Borovansky ballet was Sigrid with Laurel Martyn.

Thank you Laurel Martyn for wonderful memories. We were lucky as children in Melbourne.

Thank you Beth for your lovely memories of Laurel and those early days. It is especially interesting to hear more about Hiawatha. There is a program for it in a National Library collection. I must go back and try to find it and look at it again.

It’s lovely (thrilling, really) to read Beth Minto Marcilio’s memories. I hope that Beth will write more about Borovansky, and whatever else she remembers – so important to keep memories alive and pass them on. My mother, 90 this year, saw Pavlova in 1929 at the Golders Green Hippodrome, and remembers going to Hiawatha for one of the London seasons. One of her oldest friends (born 1904) remembered her parents – Russian – going to see Pavlova and Novikoff at one of the pre-WW1 seasons at the Palace. It’s a wonderful ‘Six Degrees of Separation’ – I know someone who saw Pavlova (and I pass that on to whoever reads this), just as I knew someone (mother’s old friend) whose father was a drummer in the army of Tsar Alexander II – I know that’s not ballet-related, but it’s a connnection I like passing on. Back to Pavlova, a great-aunt saw her twice in her final season at Golders Green in December 1930 (she loved ballet and the programme changed part-way during the week) and used to tell me that Pavlova had to be supported and turned in pirouettes (presumably because of the knee injury) – when I read Lifar’s recollection of Pavlova’s last performances where he wrote that she got little applause, I asked Aunt Jennie, and the answer was ‘No, she was called back many times, and you should have seen the flowers that were sent up’.