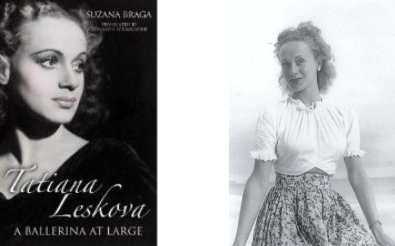

Suzana Braga’s biography of Tatiana Leskova was first published in Brazilian Portuguese as Uma bailarina solta no mundo in 2005. It went into a second edition and in late 2012 was translated into English by Donald Scrimgeour with the title Tatiana Leskova: a ballerina at large. A translation augured well for Leskova’s English-speaking admirers, and for those who were more than aware of her background as a Ballets Russes dancer in the 1940s. It is, however, an unsatisfying book from many points of view.

Perhaps the most annoying aspect of the book from my point of view is that Braga doesn’t seem to have decided on a method of telling the story. She knows the Leskova story well having being connected with her subject as a student and then as a professional dancer, and much of the book is quite intimate in approach. But at times Braga stands back and is a distant narrator with expressions like ‘So let us move on …’, or she refers to Leskova in a kind of anonymous way as ‘the young dancer’ or ‘the ballerina’. And she never really decides whether to call the subject of her biography Tatiana, Tatiana Leskova or Leskova and changes constantly between these three names and her selection of anonymous expressions. Other names get an annoying initial rather than a full first name—A. Calder, for example, who from the context I assume is the American artist/sculptor Alexander Calder. Why not pay him the courtesy of a proper identification? And too many infelicitous English phrases keep popping up at the hands of the translator: ‘[he] landed up falling in love with her’; ‘She had made her international bed and could perfectly well have lied down in it’. It all becomes a little irritating.

Looking beyond these irritations, the book probably needs to be read as a piece of oral history in written form. It is based on an extensive interview program and covers Leskova’s life from its earliest stages to the present. There are many quotes from Leskova herself and many reveal her feisty spirit:

I am a perfectionist, always thinking I can do better. I am demanding and have therefore been much criticised and even feared but I don’t do things out of malice but rather because I want, even demand, that they be better.

And on Leskova’s feisty spirit, I met her in the 1990s in New York when she kindly lent me a videorecording of her staging of Les Presages for the Dutch National Ballet. She asked me, when I had finished with it, to pass it on to the Dance Division of the New York Public Library, which I did. But several months later I received a strongly worded message from her questioning why I hadn’t passed the recording on as she had asked. Well it transpired that the recording had been sitting on someone’s desk in the Library and Leskova had not been acknowledged (nor had I). It all sorted itself out and everyone was apologetic but in retrospect her message was a clear example of her strong-willed approach to life and dance.

Many familiar names crop up through the book including those of dancers who performed with the Ballets Russes in Australia and then found themselves in South America in the 1940s—Anna Volkova and Igor Schwezoff in particular have important roles in the story. The discussion is, however, more often than not personal rather than relating to professional careers. Marcia Haydée also makes a guest appearance in a chapter entitled ‘With Marcia Haydée, a Certain Unease’ in which some difficulties that grew from a remark made by Leskova are discussed. And there are interesting thoughts about Nureyev, Massine and a host of other personalities from Leskova’s life.

I found the chapter on Leskova’s restaging of Les Presages and Choreartium, entitled ‘Doors Open’, the most interesting section of the book. It contains selected reviews of various of Leskova’s restagings and I particularly enjoyed Jack Anderson’s comment: ‘Choreartium is a vast mural in motion that makes much recent choreography look puny’. Food for thought I think. The chapter is, however, somewhat uncritical. Everything was a huge success! I didn’t see Leskova’s Presages mounted for the Australian Ballet in 2008, but Leskova told me that she was unhappy in Australia, for a number of reasons. So I would welcome comments on that staging from those who saw it.

Leskova is a larger than life personality and this book reveals the woman behind that personality. I wish, however, that the book had a stronger authorial voice.

Suzana Braga, Tatiana Leskova: a ballerina at large, trans. Donald E Scrimgeour (London: Quartet Books Ltd, 2012)

Paperback, 312 pp. ISBN 978 0 7043 7276 4

RRP £18.00. Available through online sites.

Michelle Potter, 16 February 2013