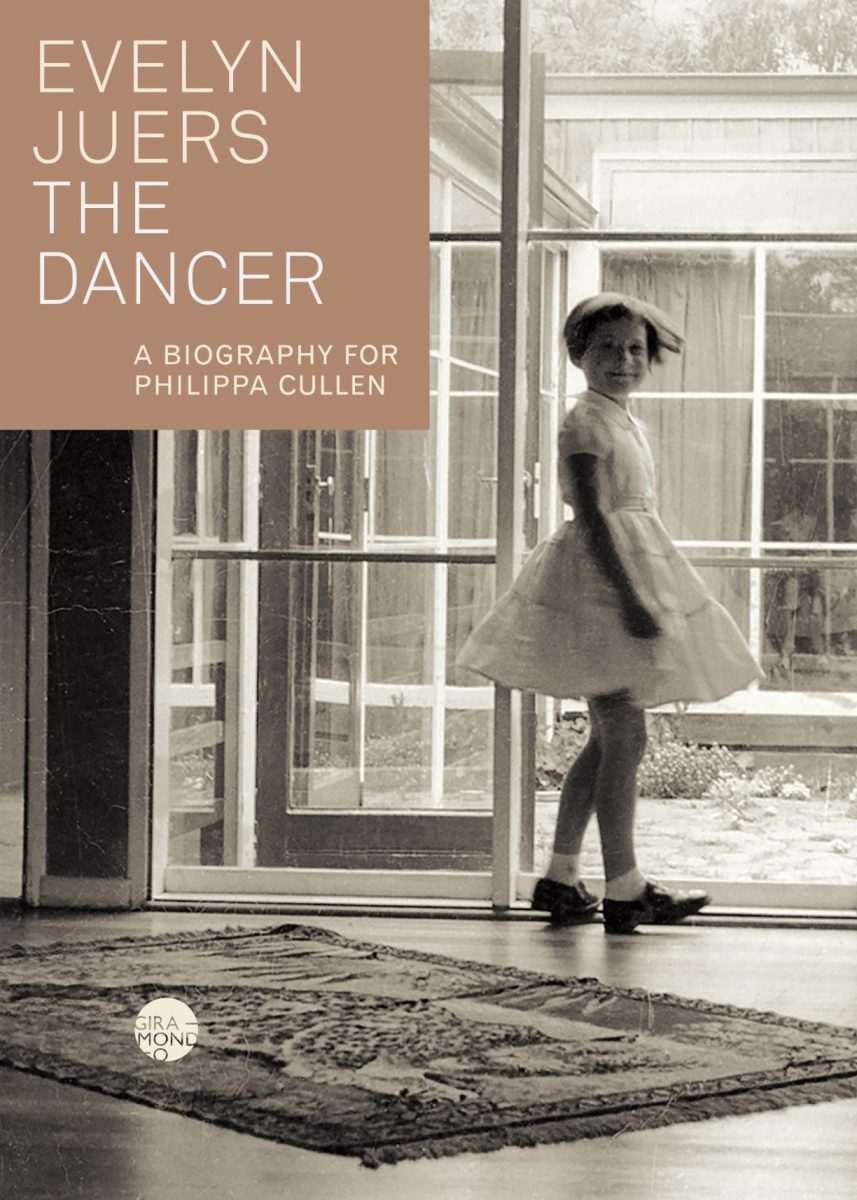

Evelyn Juers, The Dancer. A biography for Philippa Cullen. (Sydney: Giramondo Publishing, 2021)

ISBN: 9781925818727; 592 pp

RRP $39.95

This book by Evelyn Juers is spectacularly different from any biography I have read before, especially from any dance biography I have yet encountered. It is in essence the story of Philippa Ann Cullen (born Melbourne, Australia 1950; died Kodaikanal, India, 1975), a dancer who performed across the world and whose creative process involved experiments with theremins and movement-sensitive floors. Her work produced movement unlike that of most of her contemporaries, and she was at the forefront of using electronic music as an accompaniment to her work. The book is distinguished by the breadth of its author’s research and her sensitivity to the socio-political background in which Cullen worked. But it is different in two major ways from most biographies with which I am familiar: by the manner in which the author inserts her own voice into the story, and by the author’s writing style.

Before entering into the story of Cullen’s life and career, Juers investigates Cullen’s family history on both her mother’s and father’s side. This is an in depth examination drawing on as many sources as Juers was able to discover. It has its ups and downs as those who have been involved in family history no doubt have discovered. Some material is always elusive, although Juers is able to set up a clear lineage for Cullen.

Once this history has been established, Cullen’s own life takes the stage. Juers gives an insight into Cullen’s education; her dance training in Sydney at the Bodenwieser Dance Studio; her early public performances, including those with the choreographic enterprise Ballet Australia; the beginnings of her own choreography; her developing interest in the theremin and electronic music, and their uses in her creative process; and her studies at Sydney University.

Towards the end of 1972, Cullen, with the aid of a an Australia Council grant, travelled overseas to examine the role and potential of electronics in dance. She visited a host of countries in Europe, including Britain, the Netherlands and Germany as well as Africa and India; and she met and worked with a range of contemporary artists who opened up a variety of new possibilities for her. Cullen returned briefly to Australia in early 1974 and became involved in a series of seminars, workshops, demonstrations and performances before returning to India just a few months later.

But in this book there is a lot more to the Cullen story than her life in dance. Cullen’s emotional life plays a strong role throughout. There are extensive quotes from letters written to and by Cullen. There are extracts from Cullen’s diaries, which she seems to have kept religiously throughout life, and in which she appears to have recorded her dreams. Juers consistently reports on the dreams as the story progresses. Cullen’s personal notes also refer often to her love life and her concerns about pregnancies. She had many lovers and a long affair with composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, whom she met in Australia in 1970.

With regard to the constant appearance of the author’s voice as added commentary, Juers was a friend of Cullen and, in the book’s prologue, she explains how they met and how she continued the friendship after that first meeting. Her comments throughout the book expand and add an extra, personal element to the story. When both she and Cullen were in London at the same time, for example, they used to go on walks together:

That day she was wearing her thick woollen socks with sandals and we talked about wool, a predilection we shared. My mother was a knitter: on round needles she made wide swinging skirts with scalloped hems, she sculpted beanies around ponytails or plaits, topped off with colourful pompoms; when I had whooping cough she knitted me a daffodil yellow cardigan and I got better. Unselfconsciously I’d spent much of my early childhood dressed in wool. In London, as a kind of anchor, I immediately bought myself a second-hand loom and—alongside Herculean university reading lists and writing assignments—spent hours each day weaving. They say wool has memory. Philippa’s grandmother had taught her to darn, and her oldest woollen jumpers made her feel just right.

And there are many similar examples throughout the book. As a result, we meet Cullen not simply as a dancer absorbed in specific areas that were of particular interest to her, but as a forthright, funny, curious person, and ultimately as a human being who lived with an intensity that can only be described as incredibly moving—a life that was both heart-rending in its sorrowful moments but full of joy at other times.

Often, too, the author’s voice questions events or asks that events affecting Cullen’s life be seen within the wider context of the time. This is especially true of the closing section of the book dealing with the medical diagnosis that was offered as an explanation of Cullen’s death. On occasions, Juers also adds comments about her own writing process in relation to the Cullen story. She records at one stage:

I wrote to Jill Purce [one of Stockhausen’s later girlfriends] to ask if she knew Philippa Cullen, explaining that I was writing a book about her, and that I was trying to be as precise as possible about the chronology and circumstances of her association with Stockhausen.

Then follow several paragraphs regarding Purce’s response. Such sections blur the received boundaries of biography/memoir/autobiography.

As for the writing style, it is unique to Juers and at times contains sentences of a single word, or just a few words, or sentences that would in other situations be considered a clause rather than a sentence. Often the style is challenging, but then for many so was Cullen’s approach to dance. ‘I haven’t met anybody who accepts what I do without question,’ Cullen once said.

In her writing Juers also makes references to the ideas and writings of major figures from the literary world, such as James Joyce, Samuel Johnson, the Bronte sisters, and others, which open up further understanding of (or questions about) Cullen’s life and creative approach; and also tell us much about Juers’ own background as an author and reader. More challenges arise for the reader when direct quotes from original source materials are italicised within the text so the published pages regularly skip from Roman fonts to italics and back again, and from ‘I’ to ‘she’ and back again.

I found the book hard going at times, especially in the early family history sections when I wondered, despite my admiration for the depth of Juers’ research, whether the extent of detail that Juers included was absolutely necessary. But I was constantly smitten by various sections as I traversed the story. They included a section on Cullen’s return to Australia from overseas, briefly in the 1970s, when the world that unfolded on the pages of the book was strongly evocative of a dance counter-culture that existed in Sydney (and elsewhere in Australia) at the time. Then there was the dramatic and very moving story of Cullen’s last days in a remote town in India in 1975, when the author’s voice queried the nature of the physical condition that led to Cullen’s death, and when those who had helped her through her last days added their thoughts to the epilogue.

After finishing the book I felt the need to go back and start reading it again when those parts of the book that I initially found not so relevant to the essential story would probably make more sense. In fact I wonder whether I will regret some of this review when I do reread!

My closing thoughts, however, are that The Dancer is extraordinarily dense with information, ideas and challenges but is a remarkable, beautifully researched, forthright book. A bit like the best dance really.

Michelle Potter, 21 December 2021