13 October 2023. St. James Theatre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Platinum is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. It has remarkable resistance to corrosion, even at high temperatures, and is therefore considered a noble metal. It is the traditional gift used to mark the 70 year anniversary of a relationship.

That makes Platinum a well-chosen title for this single performance in the Company’s home theatre of St. James, Wellington. The 70 year legacy of this intrepid little troupe of dancers reaches back to the legendary Poul Gnatt, and equally heroic Russell Kerr and Jon Trimmer, among many others. That mantle now falls on younger shoulders to maintain the morale, health and welfare of the dancers, as of us all, for the next 70 years.

The program comprised four group works, six pas de deux and two solos, each of which will have been somebody’s favourite.

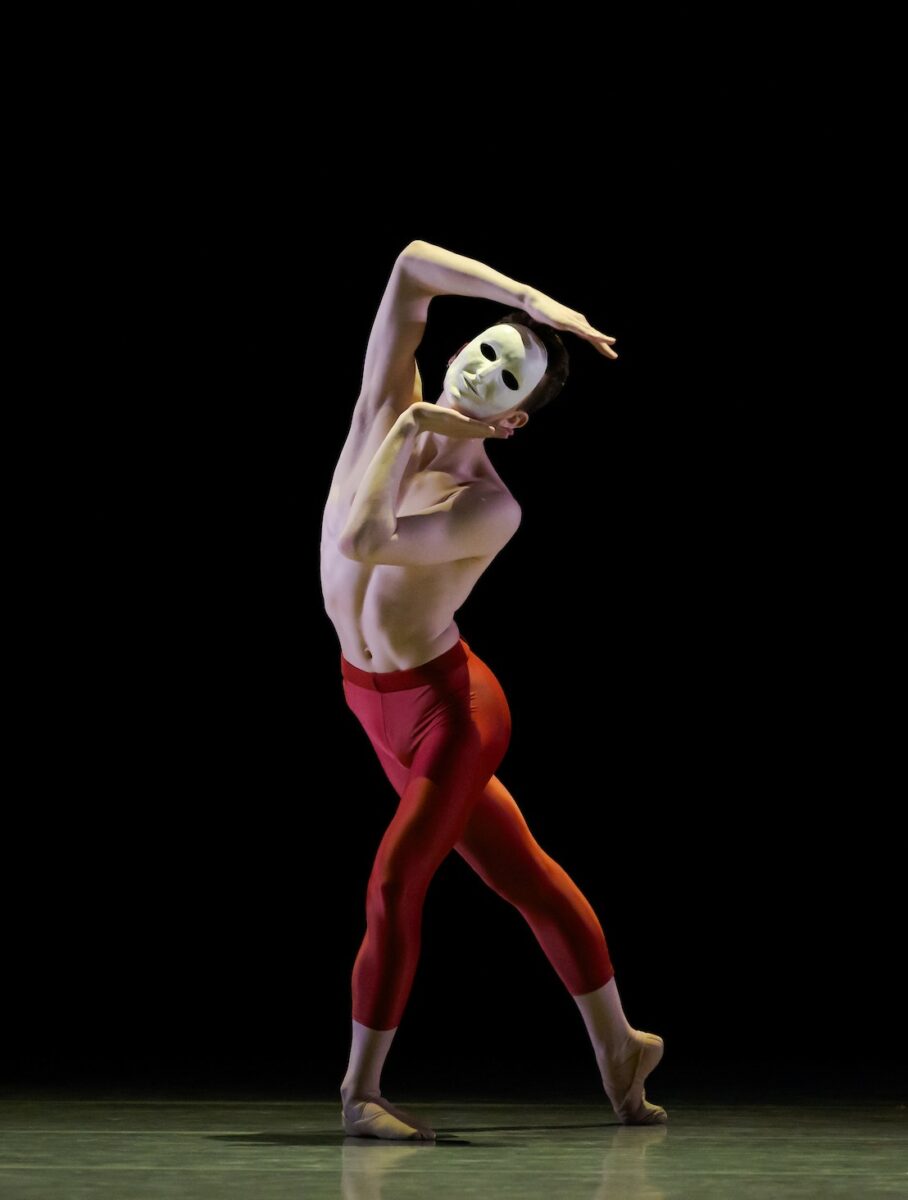

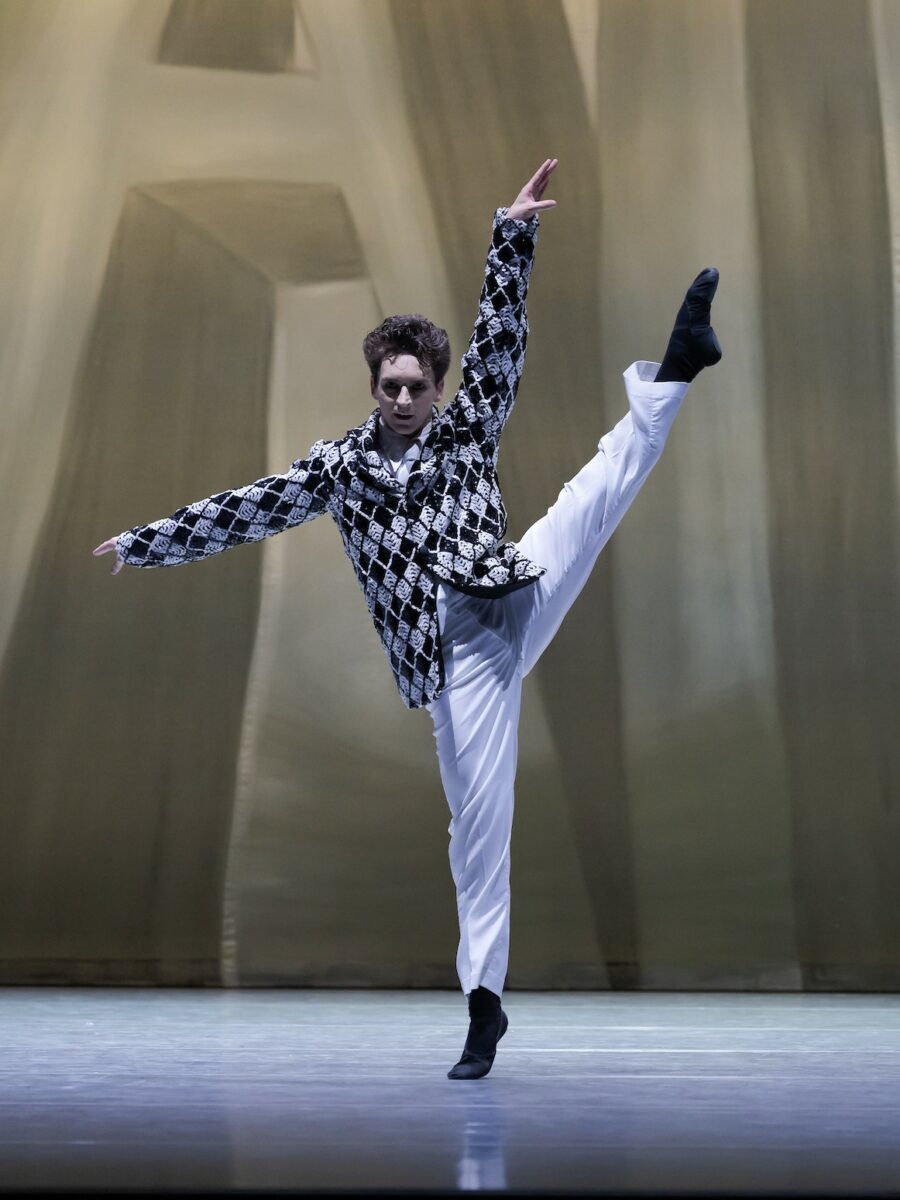

The opening work, Te Ao Mārama, by Moss Patterson, on his whakapapa (lineage), seen in the Company’s recent Lightscapes program, maintains its integrity in a strong haka taparahi performance by the all-male cast. Later in the program an all-female cast performed Stand To Reason, Andrea Shermoly’s impressive tribute, as strong as any haka, to the Suffragette pioneers. Two male solos, Val Caniparoli’s Aria, a striking work to Handel, and Mark Baldwin’s Nobody Takes Me Seriously to the rhythmically lively song by Split Enz, were both stylishly performed.

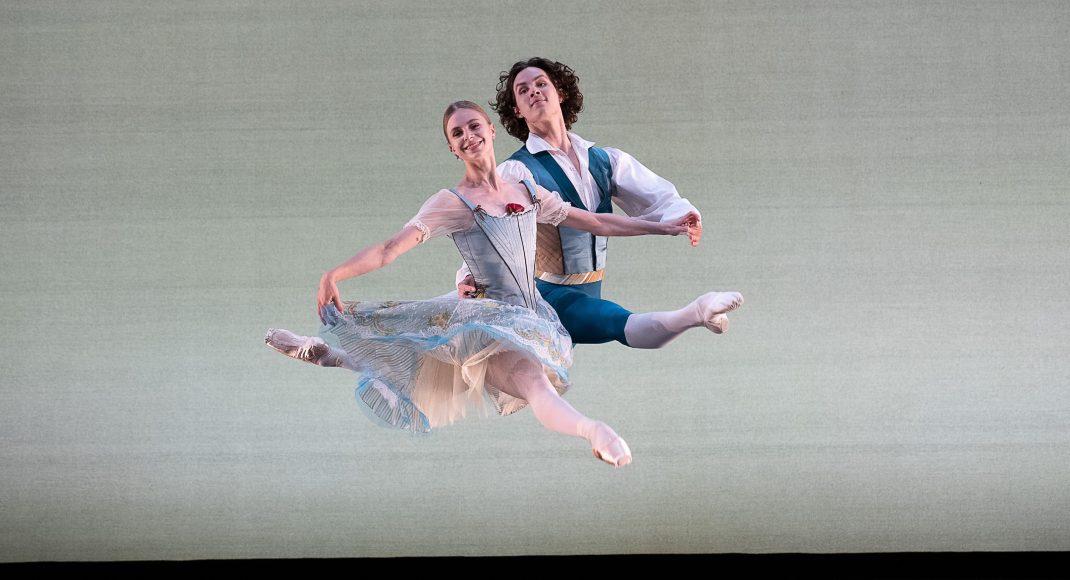

There is real challenge for a pas de deux to capture the style and context of its full-length parent work, though the Don Quixote and Black Swan items did achieve this admirably. We saw Mayu Tanigaito in both, shining as a dancer of highest calibre, her fabulous technique always serving interpretation, never the other way around.

Sara Garbowski in the Act 2 excerpt from Giselle gave an exquisitely poetic performance with beautifully judged dynamics and phrasing of movement. This was from the celebrated production by Ethan Stiefel and Johan Kobborg in 2012, followed by the outstanding feature film directed by Toa Fraser—the best film the Company has ever produced of its repertoire. It’s worth noting that the recording here was by Orchestra Wellington conducted by Michael Lloyd, so the music’s calibre for dancing was guaranteed.

I will confess my concern at the poor amplification of the music accompaniment for several of the other items, however. Does the St. James Theatre need to invest in installation of a better quality sound system?

Unusually, none of the items carried a staging credit. The Bournonville works, Flower Festival in Genzano and La Sylphide, were challenged to capture the distinctive technique and vivacious style of the Danish heritage that this company inherited from Poul Gnatt all those decades ago.

The final work, for full company, was a premiere—Prismatic, choreographed by Shaun James Kelly, a tribute to the Company’s landmark work, Prismatic Variations, made by Russell Kerr and Poul Gnatt in 1959. There was an attractive energy, personality and enthusiasm from this cast, with a spirited final image of a dancer poised aloft high above all the group, suggesting airborne hope. It was in considerable contrast to the original choreography, five couples in a work of abstract, astringent and timeless classicism, echoing the geometric design of backcloth by Raymond Boyce.

The music—Brahm’s Variations on Haydn’s St Anthony Chorale—always seemed to flood the auditorium with joy and elation. Here in a recording by the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Herbert von Karajan, you would expect no less, but again the theatre’s amplification seemed unable to offer the exhilaration we remember as an intrinsic part of the choreography.

It seemed a missed moment not to have brought on stage the incoming Artistic Director, Ty King-Wall, and the new Executive Director, Tobias Perkins, so we could welcome them—and also thank the outgoing Interim Artistic Director, David McAllister, for having stabilised the Company during its transition year.

Roses are the traditional flowers to mark 70 years and even one bouquet would have brought a sense of occasion and celebration to the stage full of talent. Instead, I came home and picked at midnight the single rose left in my windswept garden to place in a vase, as gratitude for seven decades of dancers who always gave and give their all.

Three talisman photos grace the printed program—Mayu Tanigaito and Laurynas Véjalis in Black Swan pas de deux; Patricia Rianne and Jon Trimmer in the 1978 production of The Sleeping Beauty; Russell Kerr and June Kerr in Prismatic Variations, 1960. Roses to them all.

Jennifer Shennan, 15 October 2023

Featured image: Scene from Shaun James Kelly’s Prismatic. Royal New Zealand Ballet, 2023. Photo: © Stephen A’Court