In a move to keep working during the COVID-19 pandemic, BalletX, a contemporary company based in Philadelphia, PA, recently presented a virtual season of four dance films from four choreographers—Rena Butler, Loughlan Prior, Caili Quan and Penny Saunders. Each choreographer took quite a different approach to the commission and watching such a diverse program was certainly an interesting experience.

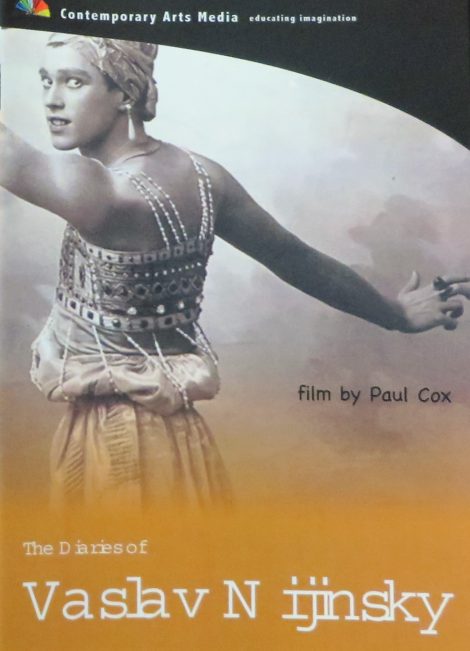

Loughlan Prior is well-known to Australian and New Zealand dance audiences. Australian-born and educated in Melbourne at the Victorian College of the Arts, he is currently resident choreographer with Royal New Zealand Ballet. He has made work for a range of companies in addition to RNZB, including Queensland Ballet, and his schedule for 2021 includes new works for RNZB, Singapore Dance Theatre, Ballet Collective Aotearoa and Chamber Music New Zealand.

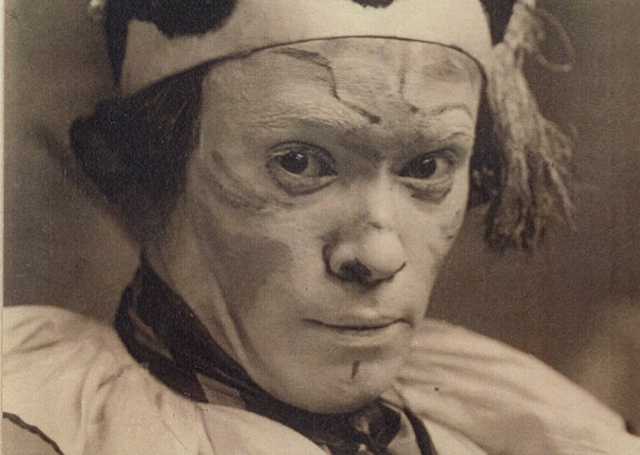

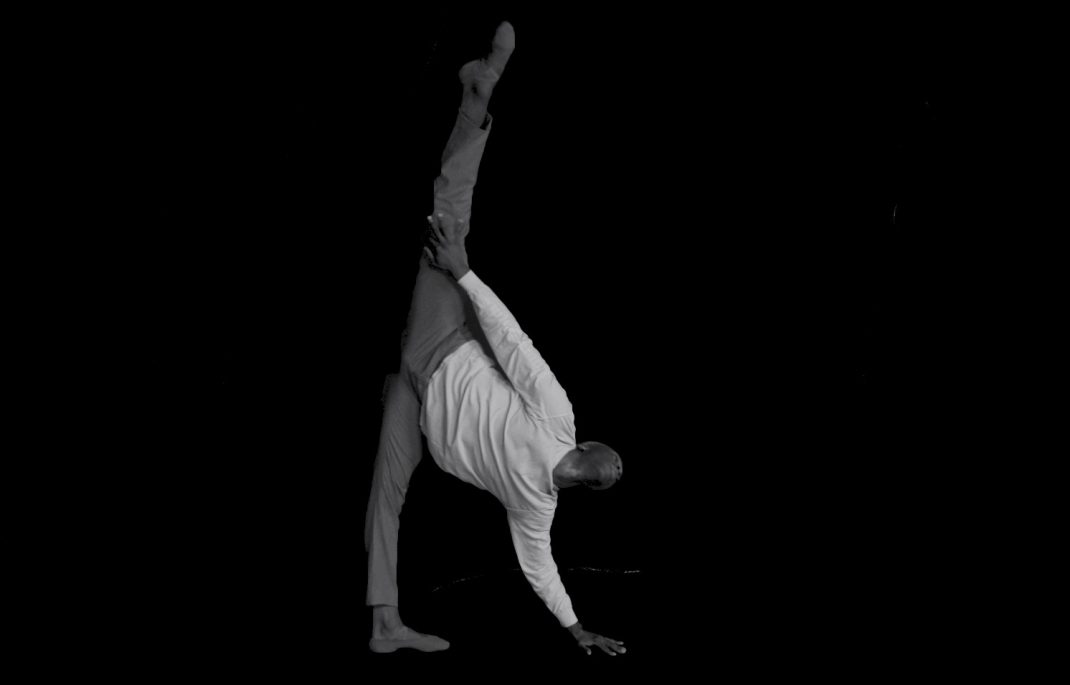

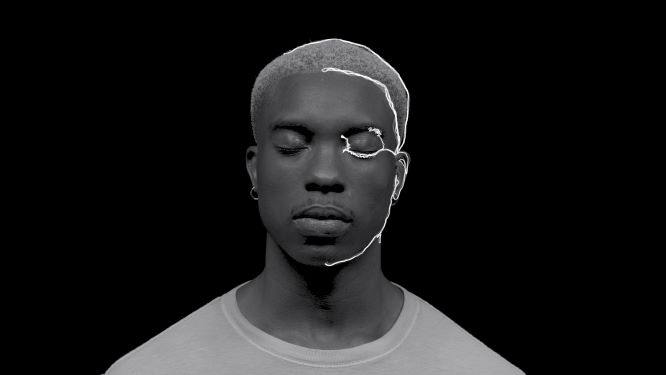

Scribble was his work for BalletX Beyond, as the newly established virtual program is called. It was made on three dancers and filmed in black and white. For me it was the most interesting film of the four, particularly because of its choreographic approach, which blended the vocabulary of ballet (the female dancer, Andrea Yorita, danced on pointe) and contemporary movement. The two male dancers performed strongly with Zachary Kapeluck partnering Yorita throughout, and with Stanley Glover showing his fabulous, long-limbed flexibility and highly expressive hands and fingers.

The ‘scribble’ of the title was created by Glynn Urquhart and consisted of white lines of animation that sometimes seemed to be generated by the dancers’ movements, at other times by the music, and at others simply out of nowhere. Occasionally the animation morphed into figures of the dancers, or vice versa. Danced to a score by Melbourne-based composer Gareth Wiecko and filmed by Daniel Madoff, Scribble was quite mesmerising.

Scribble was the only one of the four films that was not recorded at a site specific venue. The others were filmed across a range of venues in Greater Philadelphia including Natural Lands’ Stoneleigh and Idlewild, el Centro de Oro, Sea Isle City, St Malachi Church, Belmont Stables, and the Navy Yard.

Of the three other works, I found Caili Quan’s Love Letter particularly moving. Quan’s home country is Guam and the music, which was a mixed bag of items, reflected the islands, especially the islands of the Pacific (although a Harry Belafonte song was included). It was something of a meditation on whom and/or what the choreographer loved, and perhaps missed, at particular stages in her life.

The film began on a beach with a beautiful solo from Francesca Forcella who seemed to be searching her mind for remembered moments. The conclusion began with Richard Villaverde dancing on a rooftop overlooking a cityscape. He was eventually joined by Forcella and we could speculate on what their relationship was as they moved towards and away from each other. But in between this beginning and end, the film moved from venue to venue and the whole was structured so we were taken suddenly from place to place, person to person, just as the mind jumps from thought to thought. It was totally engrossing.

Ricochet, choreographed by Penny Saunders on the subject of the American cowboy, left me a little cold, largely because the choreography was not all that inspiring. There are only so many times when poses that mimic the position taken when riding a horse can generate interest. Similarly with lines of dancers walking through grassland. But the setting, especially the beautiful rural landscape, was a joy to look at, as was the filming so that the whole work looked as though it was showing on an old-fashioned television screen.

The Under Way (working title) is by Rena Butler and it too was choreographically uninspiring. It relied for impact more on camera angles, mime, colour changes and other cinematic techniques. I also found it hard to understand exactly what Butler was trying to say. There were references to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Somewhere over the Rainbow from the film version of The Wizard of Oz, statues of prominent people (now considered racist?), racism itself, and other issues. One thing that made sense was the comment of the dancer who closed the work when he spoke about the things he could do. His skin was white and he finished with the sentence ‘I can breathe.’ But it was not clear to me how the rest related to that pertinent, contemporary comment. The Under Way needs a lot of work I think.

This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing anything by BalletX. It is a strong company and every one of the dancers has something special to offer. Stanley Glover is spectacular and I especially admired the work of Andrea Yorita for the expressiveness that she offered in every role, and for the way her movement fills the space around her body.

Access to the works of BalletX Beyond is via a subscription-based streaming platform, which is located at https://www.balletx.org/.

Michelle Potter, 17 December 2020

Featured image: Stanley Glover in Loughlan Prior’s Scribble. BalletX Beyond, 2020. Screenshot by Daniel Madoff

–

–