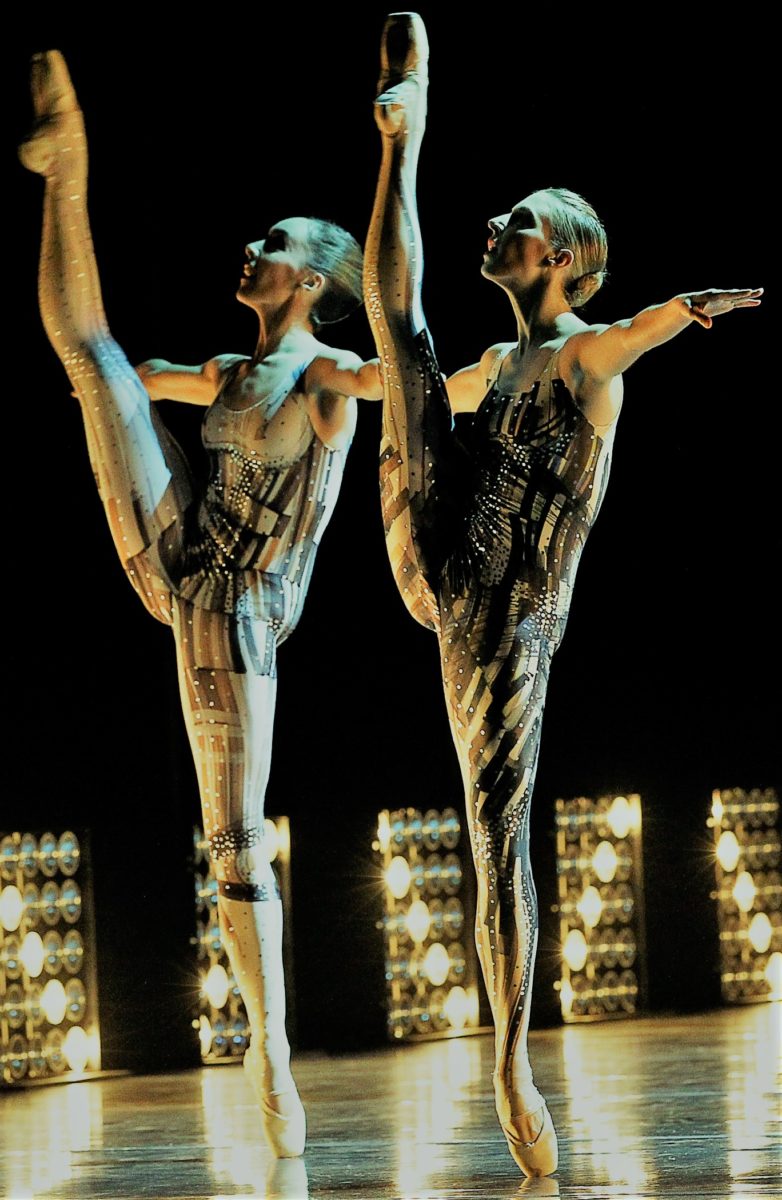

- The Australian Ballet in 2018

Details of the Australian Ballet’s 2018 season were revealed in September and this year Canberra audiences can anticipate a program from the national company. The Merry Widow, which David McAllister has called ‘a fantastically well-constructed soufflé’, was created for the Australian Ballet in 1975 as the first full-length production commissioned by the company. It will open at the Canberra Theatre Centre on 25 May and run until 30 May. Based on the operetta of the same name, it has choreography by Ronald Hynd, a scenario by Robert Helpmann (in 1975 artistic director of the Australian Ballet), and music by Franz Lehar. It will also have seasons in Sydney and Melbourne.

But beyond soufflés, and for those who like their ballet to have more intellectual input, an interesting program is scheduled for Melbourne and Sydney. Called Murphy, it honours the contribution Graeme Murphy has made to the Australian Ballet, which he joined from the Australian Ballet School in 1968. Programming is not yet complete, apparently, but we know that the main item on the program will be the return of Murphy’s Firebird, which he created for the Australian Ballet in 2009.

Here is a quote from Murphy from a story I wrote for The Weekend Australian in February 2009:

I want to give the audience the magic that they believe Firebird is. It will be a rich and opulent experience for them. Besides, the score is completely dictative of the narrative, which makes it hard to stray from the story. Firebird is imbued with Diaghilev’s thumbprint.

I am keeping all the elements of the work, the symbols of good and evil for example, but I will be focusing in a slightly different way. It will be a little like the world of winter opening up to let in the spring.

As for the rest of the season: Maina Gielgud’s production of Giselle will return for a season in Melbourne, while Sydney will have a return season of Alexei Ratmansky’s wonderful Cinderella; there is a new production of Spartacus in the pipeline, which will be seen in Melbourne and Sydney; Melbourne will have an exclusive season of a triple bill called Verve with works by Stephen Baynes, Tim Harbour and Alice Topp; and Adelaide will see The Sleeping Beauty.

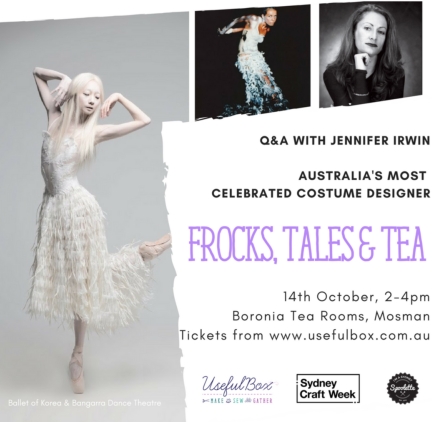

- Jennifer Irwin. Frocks, Tales and Tea

Jennifer Irwin, costume designer par excellence and recipient of the 2017 Australian Dance Award for Services to Dance, will be the special guest at an event hosted by ‘UsefulBox’ on 14 October at the Boronia tea rooms in the Sydney suburb of Mosman. Irwin will talk about her creative process and what inspired her as an artist. Further information at this link.

- Andrée Grau (1954–2017)

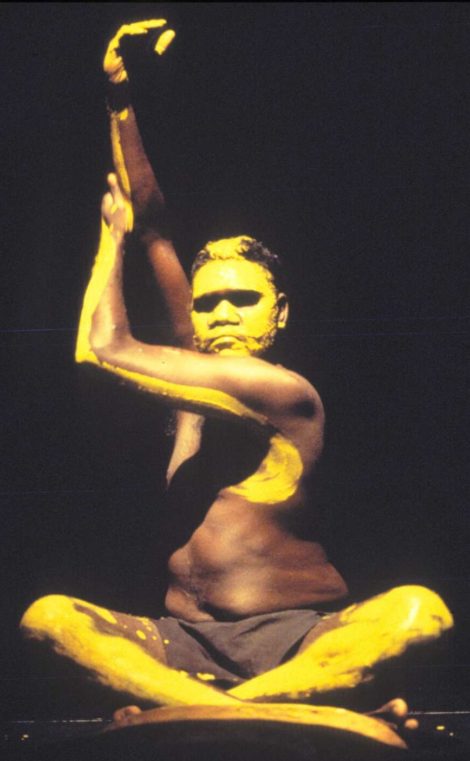

The death has occurred, unexpectedly in France, of Andrée Grau, well-known dance anthropologist, and long-standing staff member of the University of Roehampton. Grau’s achievements, which include work in Australia, appear on the Roehampton website at this link.

- Press for September 2017

‘Great flair shown in austere setting.’ Review of Circa’s Landscape with monsters. The Canberra Times, 8 September 2017, p. 31. Online version.

‘Untangling the truth.’ Preview of Gudirr, Gudirr, Dalisa Pigram and Marrugeku. The Canberra Times, 16 September 2017, Panorama p. 16. Online version.

Michelle Potter, 30 September 2017

Featured image: Amy Harris and Adam Bull in The Merry Widow. The Australian Ballet 2018 season. Photo: © Justin Ridler.