- Recent (and future) reading

Jennifer Homans’ recent book Mr B. George Balanchine’s Twentieth Century is perhaps the most spectacularly researched and written dance book I have ever read. As the title suggests, its major subject is George Balanchine, who was known to his dancers as Mr B, and Homans certainly tells us a lot about Balanchine’s life, much more than the many other Balanchine-focused books I have read. Little is held back, which sets it apart from those reminiscences that see Balanchine as perfection embodied.

Homans has drawn on a huge range of material including personal letters to and from Balanchine, diaries of dancers who worked with him, interviews with a huge range of those who knew him, and many other examples of primary and secondary source material. His relationships with his dancers and those around him, including his sexual activities, are not ignored. Nor is it only a new understanding of Balanchine that emerges in Homans’ ‘no holds barred’ examination, but we discover in depth the nature of so many of his early dancers, not to mention Lincoln Kirstein, Jerome Robbins, and so many others who were part of the scene. But what was also brilliant throughout was Homan’s discussion of how Balanchine worked with composers and used music as an essential component of his choreography. Most books I have read comment on Balanchine’s musicality but Mr B is for me the first to look in depth, and analytically, at this aspect of his work.

But basically I guess what I loved most was how Homans was able to set Balanchine’s life in a wide social and cultural context. This is what made the book outstanding and I hope to do a more detailed review of this book shortly.

Two books are on my reading list for the immediate future: David McAllister’s Ballet Confidential, shortly to be reviewed on this site by Jennifer Shennan, and a new book from Eileen Kramer, Life keeps me dancing. Inspired by Kramer’s new book, an interesting article appeared in The Guardian. Here is the link.

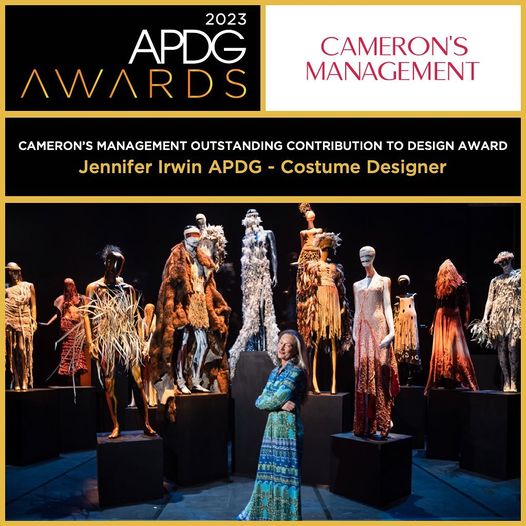

- Jennifer Irwin

I have long been a fan of the design work of Jennifer Irwin and this site features many mentions of her costume work, especially for Bangarra Dance Theatre, Sydney Dance Company and the Australian Ballet. I have admired her use of materials, the cut of the costumes she makes, the way they move with the dance, the way in some cases a single item on a costume can represent a range of ideas, and much more. So it was a thrill to read that she has just been awarded the Cameron’s Management Outstanding Contribution to Design Award by the Australian Production Design Guild.

Read more on this site about Irwin’s work for various dance companies at this tag, and on Bangarra’s Knowledge Ground. I also interviewed Irwin in 2011 for the National Library of Australia’s oral history program and that interview is available online at this link.

- Oral history: Daniel Riley

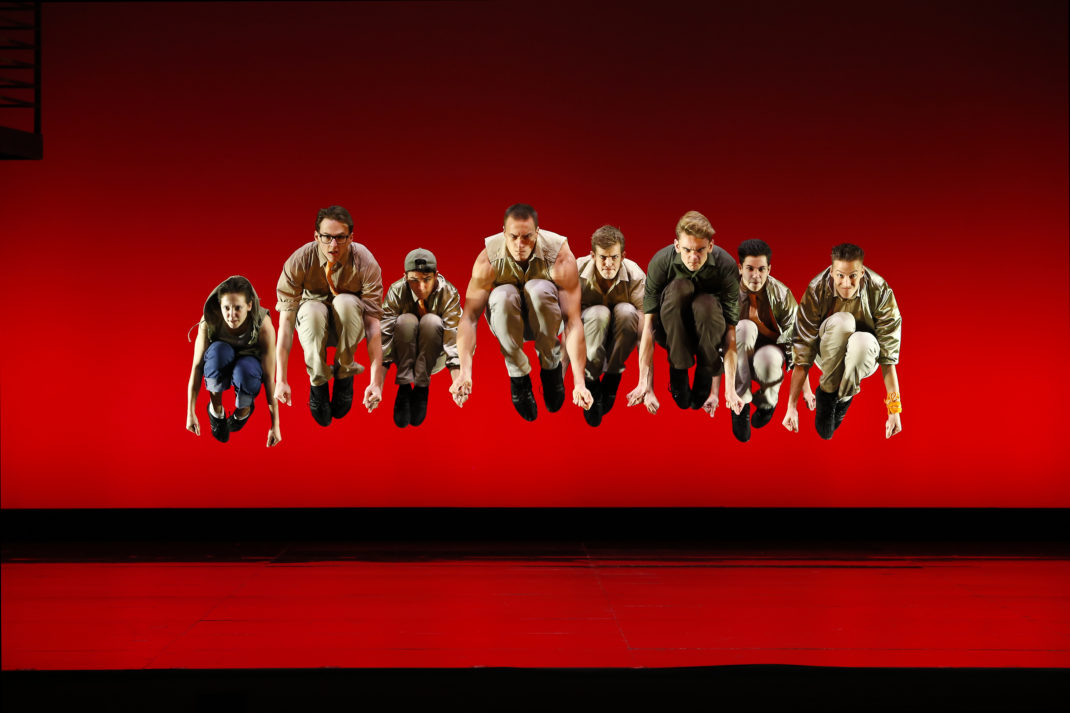

At the end of August I had the huge pleasure of interviewing Daniel Riley in Adelaide for the National Library of Australia’ oral history program. Riley, recently appointed artistic director of Australian Dance Theatre, is the company’s sixth director since its foundation by Elizabeth Cameron Dalman in 1965. He is also the initial First Nations artist to take on the role. The interview has not yet been catalogued but it was a rewarding occasion for me and the interview covers an exceptional range of material. It is certainly an important addition to the National Library’s collection of dance interviews.

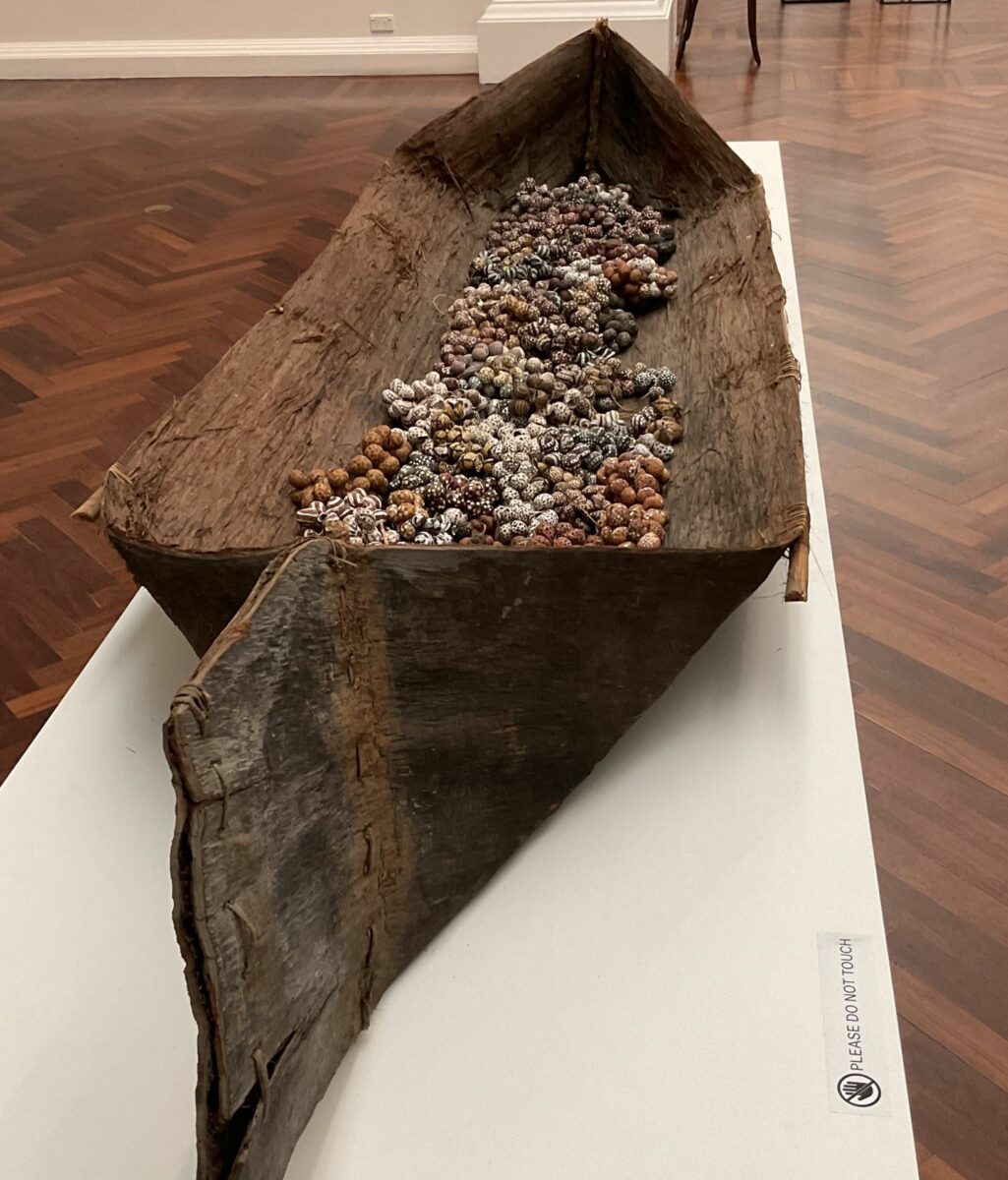

Before heading back to Canberra I made a quick visit to the Art Gallery of South Australia and the featured image for this month’s dance diary comes from that Gallery’s extensive and beautifully presented collection of art works from a range of First Nations’ artists.

- Amber Scott to retire

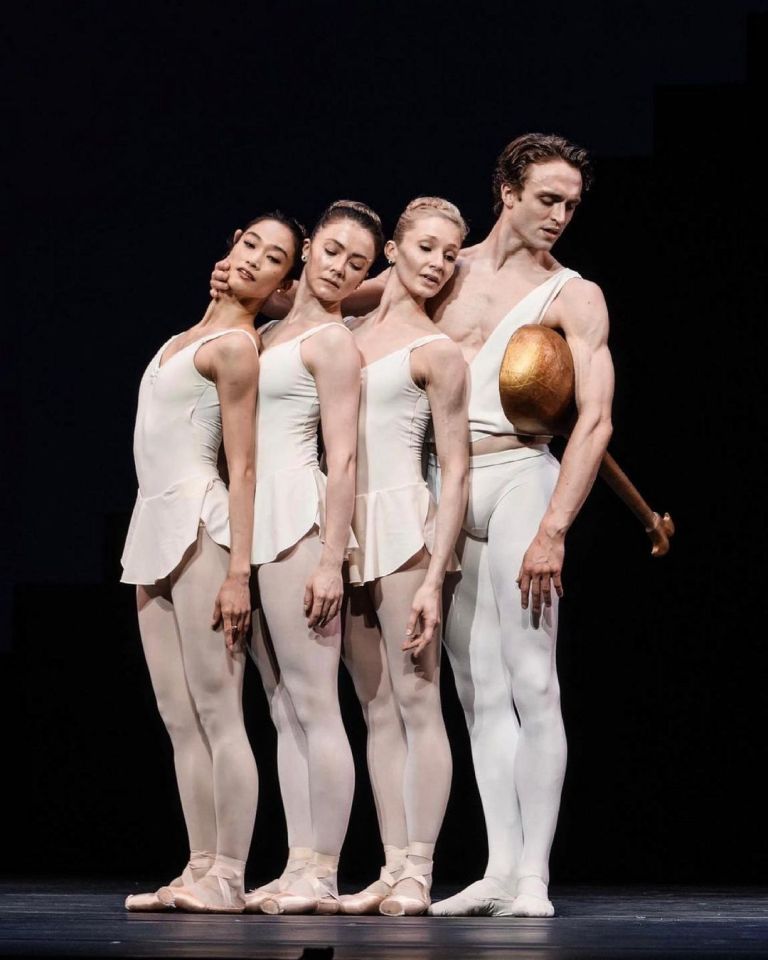

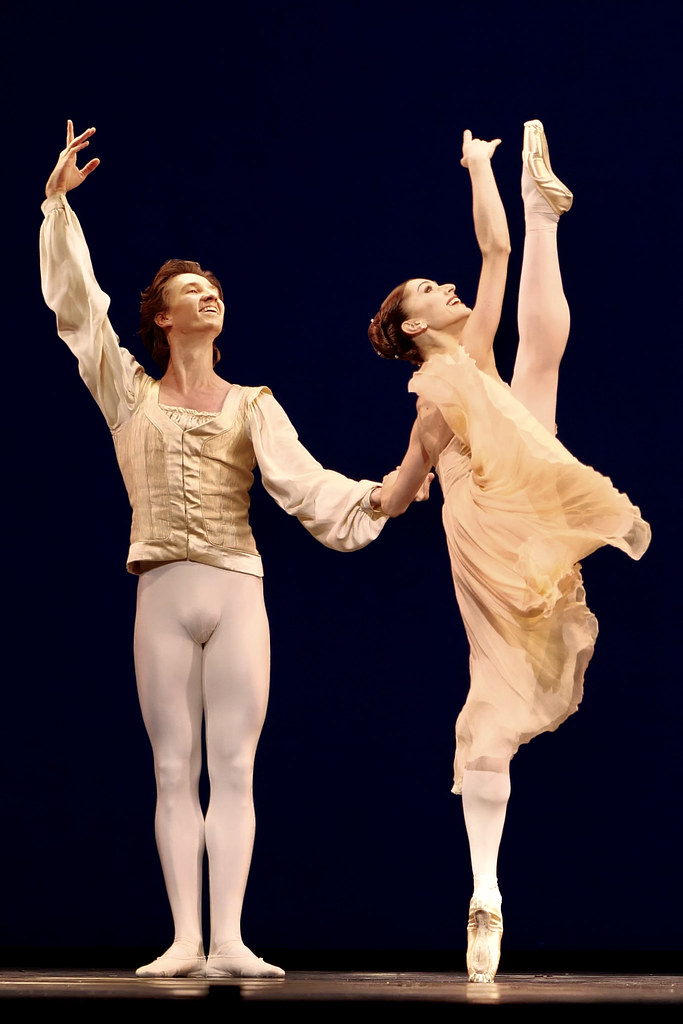

The Australian Ballet has announced that principal artist Amber Scott will retire at the end of September. Scott joined the Australian Ballet in 2001 and was promoted to principal in 2011. Her diverse career to date has included leading roles in Swan Lake (Stephen Baynes, Graeme Murphy), The Sleeping Beauty (David McAllister), Giselle (Maina Gielgud), La Bayadère (Stanton Welch), The Nutcracker (Peter Wright), Manon (Kenneth MacMillan), Onegin (John Cranko), and The Merry Widow (Ronald Hynd). She will give her final performance at the end of September in the company’s new production of Swan Lake.

For more about Amber Scott see this tag.

Michelle Potter, 31 August 2023

Featured image: Detail from (Stitched bark canoe: laden with painted snail shells), 1994 by Johnny Bulunbulun. Art Gallery of South Australia. Photo: © Neville Potter