11 March 2020. Opera House Wellington

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Lyon Opera Ballet’s Trois Grandes Fugues is a program of three separate works each set to Beethoven’s Die Grosse Fuge, opus 133. Any dance can offer access into its music. Might three distinct choreographies set to the same music enhance that experience threefold?

Originally composed for string quartet this is dense and passionate music. Here, to different recordings, are set the works of choreographers Lucinda Childs, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Maguy Marin. Would Beethoven have accepted them all? withheld copyright? encouraged the endeavour? been flattered? had preferences, maybe even a favourite? How about you? Is there any purpose to rhetorical questions? (Of course there is. I ask them all the time and like the fact that they invite but don’t insist on answers).

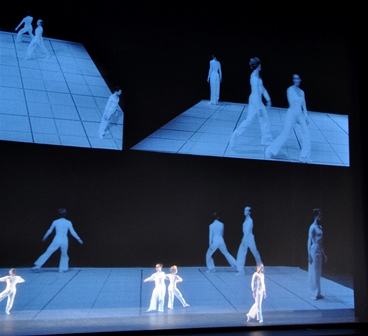

Childs’ dance was calm, analytical (she had opted for an orchestral version with its larger merged sound, very different from the distinct instrumental voices in the quartet used by the other two choreographers). Here the music score moved the dancers, six couples, through many combinations and permutations, torsos and limbs, verticals and diagonals, within the theme and variations, but chose not to transition the performers into a human, social, dramatic or poetic space. They danced to us.

(It made me long to see a revival of the similarly abstract yet highly resonant Prismatic Variations, choreographed by Poul Gnatt and Russell Kerr, from our own national ballet company repertoire).

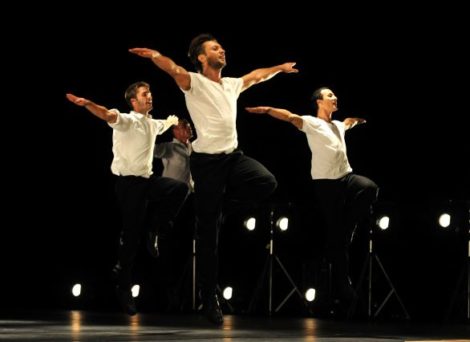

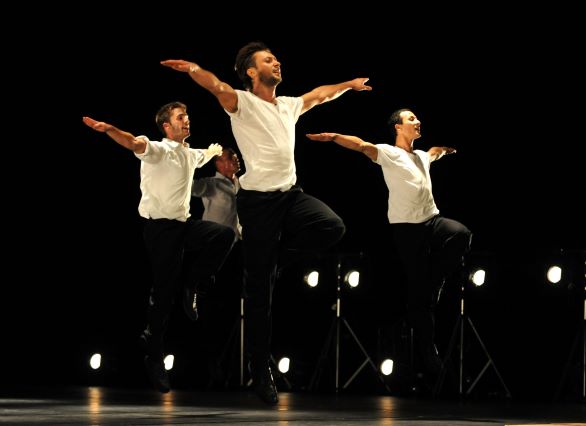

In real contrast, De Keersmaeker’s choreography was energized by its dancers, six men and two women, excited and committed performers, occasionally stepping back for a breather or to adjust their clothing—then up and at it again, full tilt, every move delivered with clarity and light. They danced for us.

Marin’s piece opened to music only, in the dark. What a powerful reminder of her extraordinary MayB, brought to an earlier festival here. That work distilled her encounters with Samuel Beckett and all the characters in all his plays—opening with a long strain of Schubert played in the pitch dark. (‘I’ve forgotten half my life, but I still remember this’—that’s Leonard Cohen in posthumous song lyrics). Then came the dancers, a quartet of women in dark red dresses, one dancer per instrument, absorbed into Beethoven’s emotion. They were occasionally airborne in galvanised elevation but only as attempt to escape, not to celebrate. At one point they moved forward and sat at the front of the stage, as if to explain something. They danced inside us.

The clean, the engaged, the deep? the morning, the evening, the night? air, water, earth? cerebral, social, wild? skin, flesh and blood? reveal, illuminate, absorb? Which would you remember the longest? Which would you prefer? You can of course say yes to everything if you don’t want to judge or to choose.

For this Festival season the artistic director invited three artists to take a week each in a lightly defined curatorial role, to guide us in anticipating and accessing their take on the forthcoming program highlights.

I accepted this as a personal invitation to curate my own Festival (which we all do to some degree anyway, depending on family responsibilities and other constraints)—so my curated version of Trois Grandes Fugues opens with New Zealand String Quartet sitting centre-stage playing the Beethoven through, first as music alone. (It’s in their repertoire, actually now in their dna, and they performed it here in recital only a few weeks ago. The players are second to none in the world so how ironic to have been sitting beside them in the audience). After all, musicians in a string quartet move in a kind of miniature ballet all their own—sustaining urgent eye contact, exchanging taut gestural signals and cues among themselves, not sending communication just one way towards a conductor who is controlling an orchestral ensemble. I’d have asked them to play it again for each of the three choreographies. Then as a sublime and anchoring epilogue, we’d have sat, audience and musicians, in total pitch darkness, while they played it all again a fifth and final time. That way we’d have come to know the music in live renditions (I don’t believe audiences listen with care to recordings …) and the middle slow movement, searching among sadness for some hope, might have become ours to have and to hold forever

Jennifer Shennan, 15 March 2020

Featured image: Scene from Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s Die Grosse Fuge in Trois Grandes Fugues, Lyon Opera Ballet. Photo © Michel Cavalca