23 August 2024. The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre

Below is a slightly enlarged version of my review of Jurrungu Ngan-Ga [Straight Talk] published online by Canberra’s CityNews on 24 August 2024. The CityNews review is at this link.

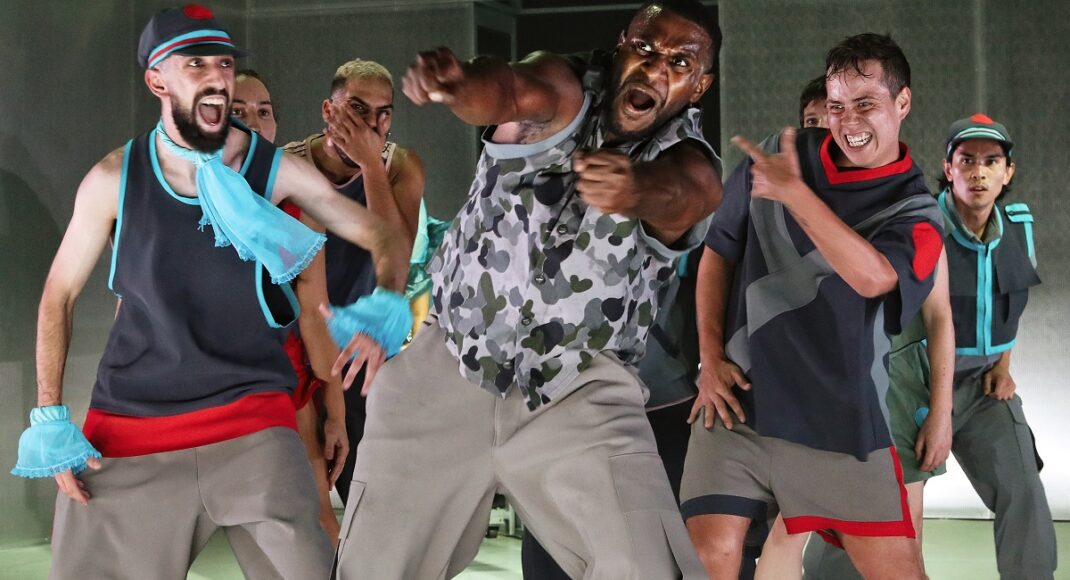

I have always thought of Marrugeku as a dance company with a strong focus on Indigenous issues. But Jurrungu Ngan-Ga, staged recently in Canberra by Marrugeku, showed just how much more the company offers audiences. In the case of this production, multi-disciplinary is a much stronger descriptive term for this company. In Jurrungu Ngan-Ga dance was a definite, probably dominant, component and the dancers were all exceptional performers. But the dance input was solidly supported by voice (both spoken and sung), video projection, and installation. It also had a cast of diverse cultural origins, including those with an Indigenous heritage as well as migrants to Australia, especially those who had been interred in immigration camps, notably on Manus Island in Papua New Guines.

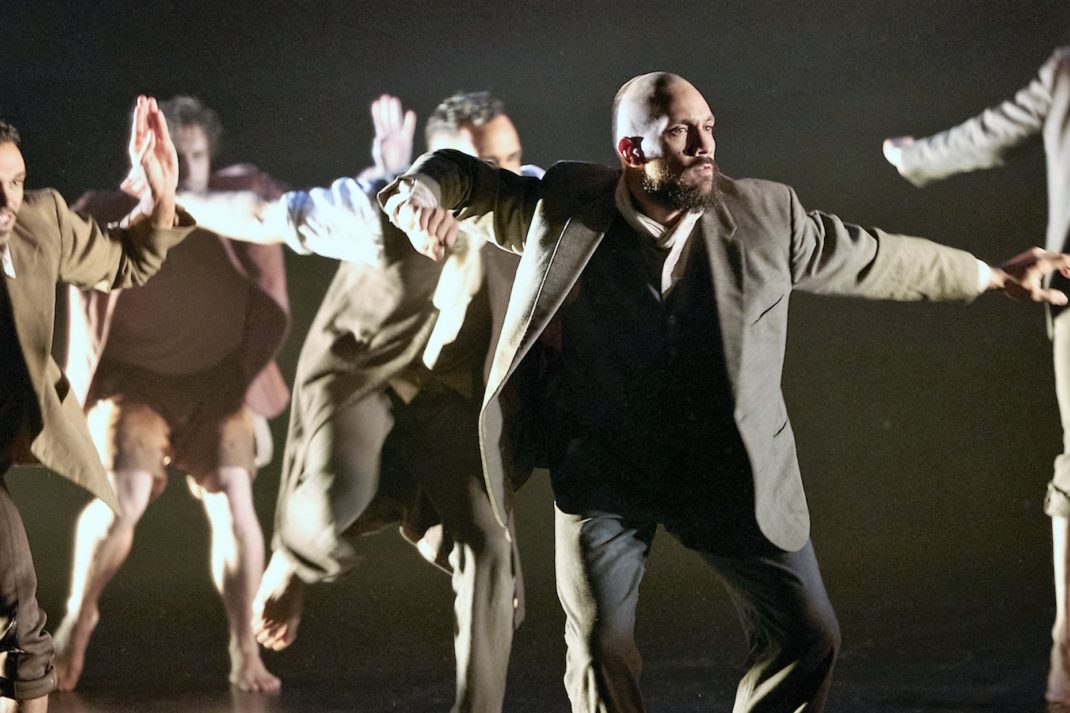

The work was largely a series of distinct scenes. It opened with a solo that gave us a look at the kind of choreography we might expect throughout the evening—dance that was twisted, complex, occasionally grounded but moving constantly across the stage space, and subtly displaying the effects of invisible forces on the body. From there Jurrungu Ngan-Ga moved from scene to scene, some more confronting than others including some prison scenes, some overtly sexual moments, and one scene that involved dancing that seemed to suggest determined resilience in the face of unimaginable personal difficulties.

Choreographically Jurrungu Ngan-Ga was diverse in its references. There were moments when moves were distinctively balletic, some that seemed clearly Indigenous, others that had a strongly Asian feel, and some that recalled hip-hop. There were even some moments when I couldn’t help thinking of Raygun and her much-discussed Olympic break-dancing performance.

Unfortunately, as is a common practice these days, the online program gave us little that helped identify performers we may not have known from elsewhere—no portrait-style images. But the male dancer who, to me, gave the strongest performance was former Canberra-based artist Luke Currie-Richardson. Tall, powerfully built, shaved head and sporting a black beard, he was at times terrifying as he manipulated a boomerang as if it were a gun, while all the time soaring through the air and always completely committed to his role. *

Bhenji Ra also gave an outstanding performance as a woman who needed to, and did talk about her ideas and opinions on life. She did it mostly from a table top, which she demanded to be set up for her. Her strength as an actor shone through.

Costumes by Andrew Treloar were an interesting mix of styles from underwear to stylish evening attire. They were also shared among the dancers and often split into several pieces with parts worn by various dancers. As for the projections, from the program it was not immediately clear who was responsible for this aspect of the show but it was more of a mirror of what was happening onstage than anything else.

Marrugeku is led by Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain and is located between Broome, Western Australia and Sydney New South Wales. Its patron is former senator, Patrick Dodson, who has been strongly involved with the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. His input into the political aspects of Jurrungu Ngan-Ga was clearly present.

With such a background Jurrungu Ngan-Ga was not an easy show to watch. It was provocative and it constantly put confronting issues before us. It ended as it had begun with a solo, which this time was angst-ridden and full of a feeling of sorrow. The work pulled no punches but certainly gave us a profound examination of shameful issues, largely those emerging from incarceration and the detention of refugees, which have affected the people at the heart of the work. Straight Talk indeed.

Michelle Potter, 26 August 2024

* For more about Luke Currie-Richardson see this link to an article published in The Canberra Times in 2016 (from the days when that newspaper actually published material about the arts).

Featured image: Dancers from Jurrungu Ngan-Ga from a 2022 production by Marrugeku. Photo: © Prudence Upton