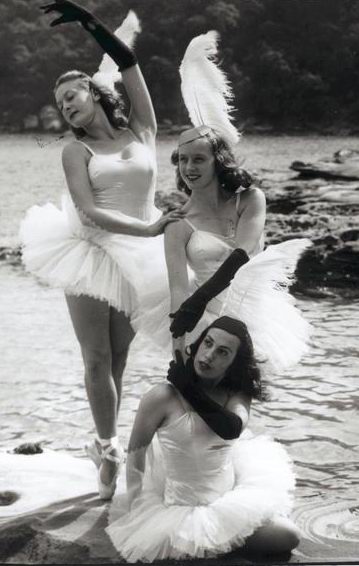

Dimity Azoury, currently a coryphée with the Australian Ballet, remembers her grandmother with great fondness. She was a ballet student in Wellington, New Zealand, and even went on as an extra when the Ballets Russes companies visited New Zealand in the late 1930s. But, Azoury tells me, her grandmother’s parents thought that ballet was not an appropriate career for a young lady, which was not an uncommon attitude at the time. So her grandmother gave up her ambitions, married and moved to Australia.

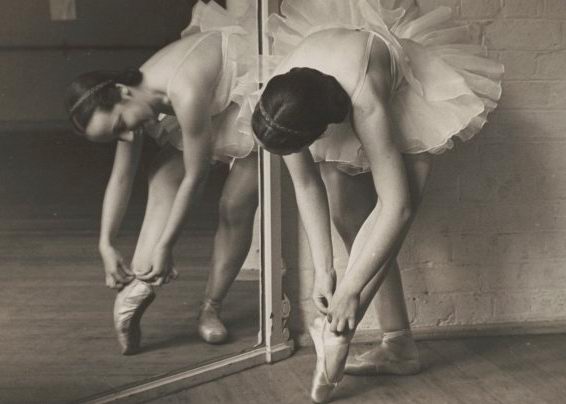

‘I often used to look at a photo of her wearing a long, Romantic tutu,’ Azoury recalls, ‘and I think it was from her that my love of ballet came.’

Azoury’s career as a ballet dancer, a career now (happily) considered a worthy course to take in life, moved another step forward just recently when he received the Telstra Ballet Dancer Award, worth the substantial amount of $20,000. Her win was announced on stage at the Sydney Opera House at the final rehearsal for Sir Peter Wright’s Nutcracker.

‘I was in a state of shock when my name was called,’ Azoury says. ‘I was shaking and found it really hard to hold on to the flowers I was given. Then, when the curtain came down, all the dancers hugged me and were so supportive. This is one of the lovely things about working in the Australian Ballet. Everyone is so generous.’

Azoury was trained first in Queanbeyan and then in Canberra at the Kim Harvey School of Dance. She was twice rejected for the Australian Ballet School but, encouraged by her parents and by Harvey, she auditioned again and was accepted in the 2005 intake. She spent three years at the school and was taken into the Australian Ballet in 2008.

‘My aspirations are all with the Australian Ballet. I love the company and feel totally involved. And now I feel I am getting opportunities.’

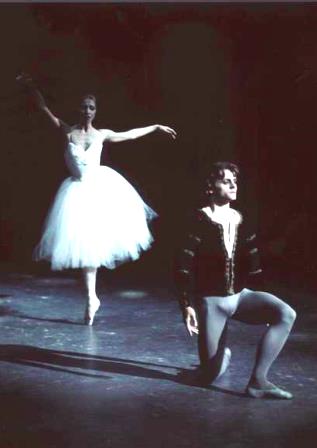

She is looking forward to the company’s production of Maina Gielgud’s Giselle, a highlight of the 2015 season, and has enjoyed rehearsing under Gielgud’s direction. Gielgud, Azoury says, knows exactly what she wants and so it is easy to find a clear focus in rehearsals. It has also been especially exciting for her to have the opportunity to try the role of Myrthe, Queen of the Wilis. There are also rumours that her much-loved deerhound, Gunther, may have a walk-on part in Act I. ‘I guess he’ll have to audition,’ she muses.

In addition to regular company repertoire, since joining the company Azoury has also performed in every one of the annual Bodytorque programs, in which her fellow dancers try their hand at choreography.

‘Bodytorque feels like a collaboration. There is no pressure on the dancers and I love being able to help my friends bring their vision to the stage.’

The year long journey as a Telstra nominee has proven to be an exciting one for Azoury. She looks back with particular pleasure on making the video each of the six nominees created as part of the year’s work.

‘We were given a lot of freedom. We were each given a colour and an element to work with —my colour was blue and my element paint. While the camera angles were set, at one stage I was given the opportunity to show how many ways I could make the paint move. It was a wonderful experience for me and a way of celebrating the Telstra sponsorship of the Australian Ballet.’

Azoury recently married Australian Ballet senior artist Rudy Hawkes. Her no-strings-attached Telstra award will most likely be spent on renovations to their house in North Melbourne.

Michelle Potter, 6 December 2014

Featured image: Dimity Azoury (centre) receives the 2014 Telstra Ballet Dancer Award. Photo: © Jess Bialek