Below is an enlarged version of my review of Twofold published online by Canberra’s CityNews on 19 September 2024. The CityNews review is at this link.

18 September 2024. Roslyn Packer Theatre, Sydney

Sydney Dance Company’s Twofold began by giving the audience a second look at Rafael Bonachela’s work, Impermanence. Bonachela, artistic director of Sydney Dance Company for more than 15 years, created this work, in conjunction with American composer Bryce Dessner, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was first seen onstage in 2021 when I masked up and braved the situation and went to see it. My review of that occasion is at this link.

Then followed the thrill of a brand-new work, Love Lock, from Melanie Lane who works across the world as an independent choreographer. Love Lock is Lane’s second major work for Sydney Dance Company, following on from the much-admired WOOF, which premiered in its mainstage iteration in 2019. See this link for my review of that work.

Lane spent her early life in Canberra and received her dance training at the National Capital Ballet School under the direction of Janet Karin. She has maintained her Canberra connections and has worked closely in recent years with QL2 Dance, Canberra’s youth dance organisation, and has also created works in Canberra in a number of independent situations.

The titles of the two works in Twofold, Impermanence and Love Lock, both raise interesting questions in the mind of those watching, but neither really explains unquestionably the nature of the works as we see them. But then it has always been Bonachela’s belief that it is the members of the audience, not the choreographer, who decide on the meaning of any dance work.

Impermanence was extremely engaging and was performed to Dessner’s score played live onstage by the Australian String Quartet. Its choreography showed Bonachela at his most intense and relentless giving rise to the dancers being able to display their outstanding ability to bend and twist the body into remarkable positions while maintaining a lyricism and a strong connection with others onstage. They worked with each other in duets, trios, quartets and often as a whole group in unison. But I was surprised by the number of times five dancers formed a group, which made me think back to Bonachela’s Cinco, a work that referred to the five decades of dance from Sydney Dance Company.

The work was lit by Damien Cooper and often the dancers and musicians were shadowy. At other times they were dark figures in brighter surroundings. Always the lighting influenced how we perceived the dancing, which came to an end with a striking solo danced to a song from singer and songwriter Anohni.

As for Love Lock, given Lane’s Canberra connections it was more than tempting to think back to the strange role love locks have had in Canberra. In 2015 a growing collection of love locks, that is padlocks that represent everlasting love that are sometimes attached to a bridge before having their keys thrown into the water never to be retrieved, were forcibly removed by the National Capital Authority from the bridge leading to Queen Elizabeth II Island on which is housed Canberra’s carillon.

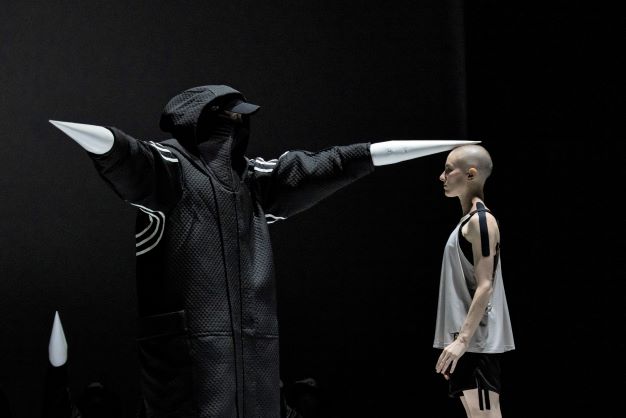

But Love Lock was a reflection on folk or community dancing, which Lane said she sees as celebrating what it means ‘to connect with each other through our bodies and essentially what it means to be human.’ In the early moments of the work the choreography was characterised by lines of dancers, dressed in shiny black, largely unadorned outfits, filling the performance space and working in a somewhat geometric fashion. Slowly, however, this structured format gave way to movement that was more eccentric, thus losing to a certain extent its folkloric appearance. As the work progressed dancers began appearing in remarkable and individualistic costumes from designer Akira Isogawa. The costumes were of various colours, often made with softly draped material, and often quite sharply and unexpectedly protruding beyond the line of the body.

Love Lock was also lit by Damien Cooper and was performed to a driving score commissioned from [Chris] Clark. The movement continued to appear intense and individualistic with changing physical connections between dancers until the closing moments when a calm descended over the group.

Love Lock is a work for this century. It is brash at times but always demanding of our thoughts about humanity and how connections may change over time. A triumph for its choreographer and her collaborators.

Michelle Potter, 20 September 2024

Featured image: (l-r) Dean Elliott, Emily Seymour, Sophie Jones and Mia Thompson in Melanie Lane’s Love Lock. Sydney Dance Company, 2024. Photo: © Pedro Greig