16 November 2013 (matinee), Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

I was startled to see, when looking at the Australian Ballet’s website to check the casting for my Sydney subscription performance of Paquita and La Sylphide, that Paquita was advertised as a Romantic ballet—’the last flowering of the Romantic ballet’. Elsewhere on the website the program was described as ‘the first and last [of the] great Romantic ballets on one double bill’. The original, full-length Paris production of Paquita (1846) might have been in the Romantic tradition, although that is disputed by some, but what the Australian Ballet has been presenting is definitely not a Romantic work. Marius Petipa made additions to the original Paquita when he restaged his version in Russia in 1881 (1882 new style date). Those interpolations with music by Minkus are, I believe, what most companies now perform. The complete ballet was staged relatively recently (2001) by Pierre Lacotte for the Paris Opera Ballet, but not many other companies have a full-length production in their repertoire. Without the rest of the ballet, the Petipa arrangements can scarcely be called Romantic, although the Spanish overtones we see and hear in the Petipa excerpts do allude to the Spanish elements of the full-length ballet.

That aside, it was a thrill to see Daniel Gaudiello taking the male role in my Sydney viewing of the Australian Ballet’s excerpts from Paquita. What I love about Gaudiello’s dancing (apart from his technical abilities) is his wonderful approach to partnering. He is so attentive to and caring of his partner (Lucinda Dunn on this occasion) without being merely a ‘porteur’. When he stands back from her and lifts his arms to an open fifth position he is not only triumphantly showing her off as the ballerina, but also showing his own polish and charisma as a true ‘danseur noble’. He has great style.

Of the variations I especially enjoyed the second variation, subtly and gently danced by Jessica Fyfe, and the dancing of the two demi-soloists, Vivienne Wong and Benedicte Bemet, the latter certainly a rising personality.

I was pleased too that my previous disappointment with the staging of La Sylphide dissipated somewhat with a second look. This time I thought there was much more feeling for the Romantic style in the second act and a better contrast between the first and second acts.

Perhaps it was Reiko Hombo, who gave a strong, individualistic interpretation, beautifully danced, of the Sylph that made the difference. The lightness and height of her jump; her softly unfolding, beautifully controlled arabesques; her lovely rounded arms; and her supple upper body gave the right technical feel to the role. In addition, her interpretation was consistent and well thought through. There was a definite wickedness of intention there under all that charm as she made every effort to convince James of her wish that he join her in her forest realm. It brought home very nicely that ‘beautiful danger’ that respected Danish scholar Erik Aschengreen so perceptively wrote about many years ago as being a defining characteristic of the Romantic era. And Hombo carried this approach through into the second act.

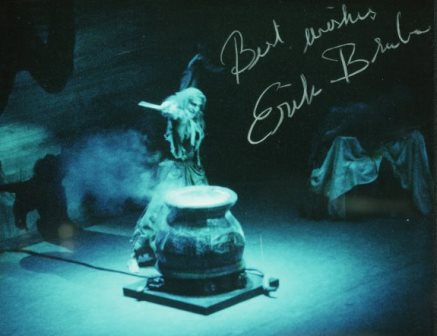

Hombo was partnered by Chengwu Guo as James and he had, I thought, settled well into the role since my previous viewing. Perhaps again it was Hombo who made the difference. She gave him something to respond to, and as technical partners they work well together. Halaina Hills as Effie and Amy Harris as the lead Sylph in Act II also added a certain strength to the overall production. But I regret that the important role of Madge always seems to degenerate into something a little manic. It has been a long time since there has been a really powerful performance in Australia of that role. Without a strong and convincing Madge the ballet loses much of its intent.

My earlier post on this program is at this link.

Michelle Potter, 17 November 2013