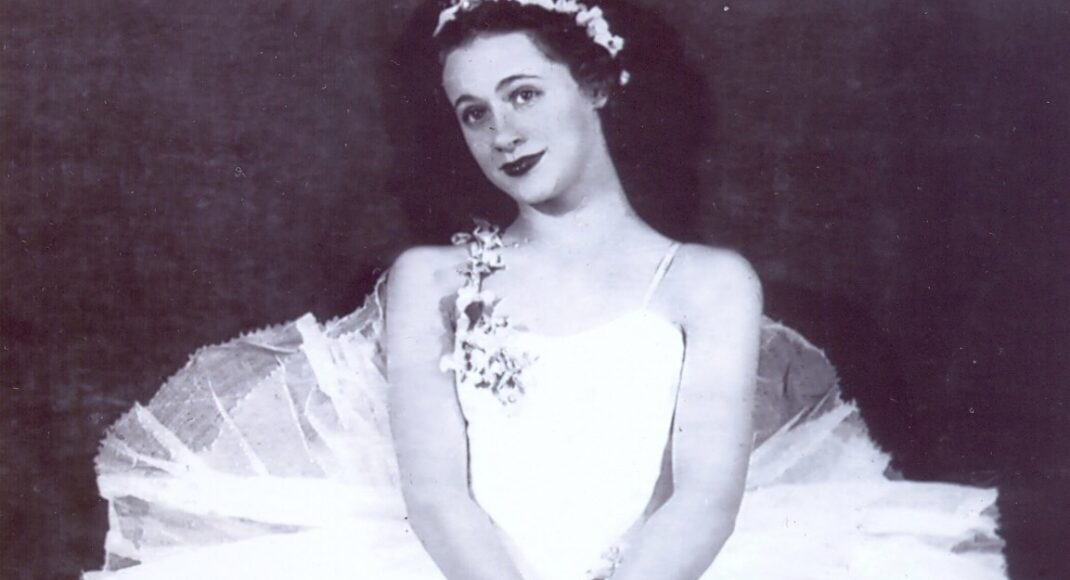

Some time ago, Tatiana Leskova, former dancer with the Ballets Russes and with a significant career after those experiences, sent me a copy of her biography, Tatiana Leskova. Uma Bailarina Solta No Mundo. It was the original edition written in Brazilian Portuguese by Suzana Braga. Eventually an English edition was released, Tatiana Leskova. A Ballerina at Large, and I gave my Portuguese edition (which I couldn’t read!) to Valrene Tweedie (who could read it). But I kept the DVD that was part of the original edition. As for that DVD, there were moments when English and French were used by Leskova and the people with whom she was dealing, but the dialogue and commentary were basically spoken in Portuguese. But luckily for me there were English subtitles available (although they had not been created in very good English, and they also often featured incorrect spelling).

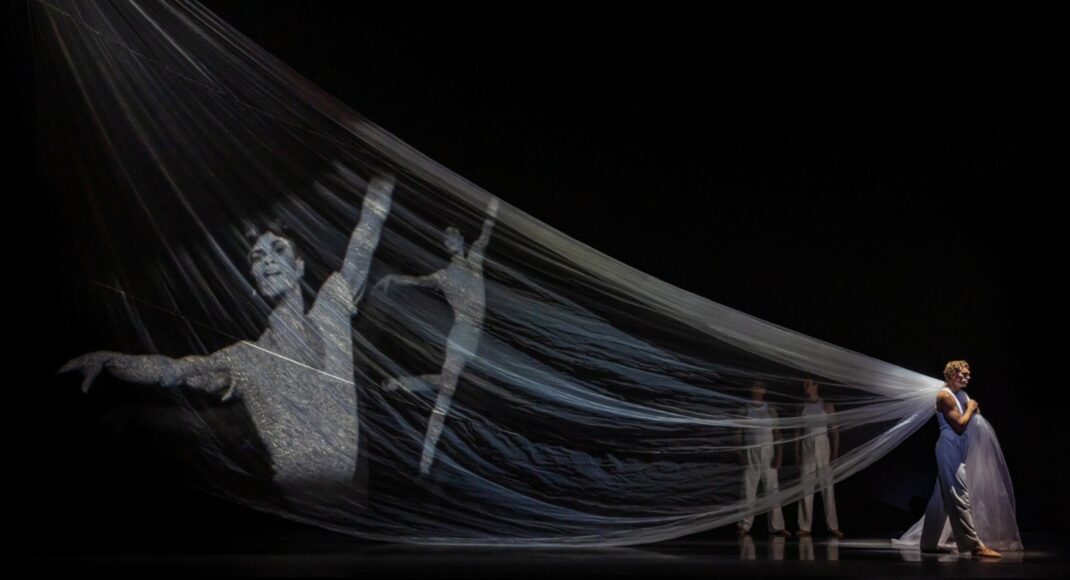

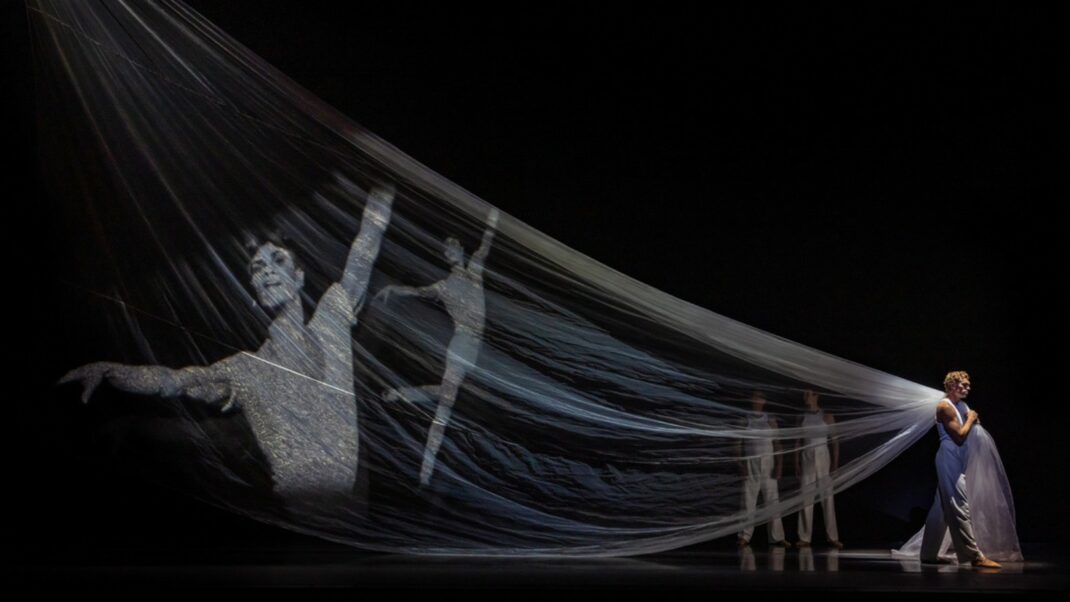

But a recent major clean-up of my study brought the DVD to light once more and I watched it again. It contains some wonderful images from Leskova’s early career, some footage (mostly fairly grainy) of her performances in works from the 1930s and 1940s as well as footage and images of her later career as a dancer in Rio de Janeiro. There are scenes of her various friendships, including with fellow Ballets Russes dancer Anna Volkova; scenes of her teaching at the school she established in Rio; and interviews with some of the Brazilian dancers she trained.

A number of aspects of the unfolding story stood out for me. I was interested, for example, to hear comments from Sir Peter Wright, who commissioned Leskova in the 1990s to restage Choreartium for Birmingham Royal Ballet, and Wayne Eagling of the Dutch National Ballet for whom Leskova also restaged Choreartium, this time in 2001. Wright said she was ‘fighting for everything and being so passionate about it.’ Eagling said of her work, ‘She demonstrates what feeling should be.’ And they both talk about how she never compromised and was ‘tough’. And many other words of wisdom come from them both.

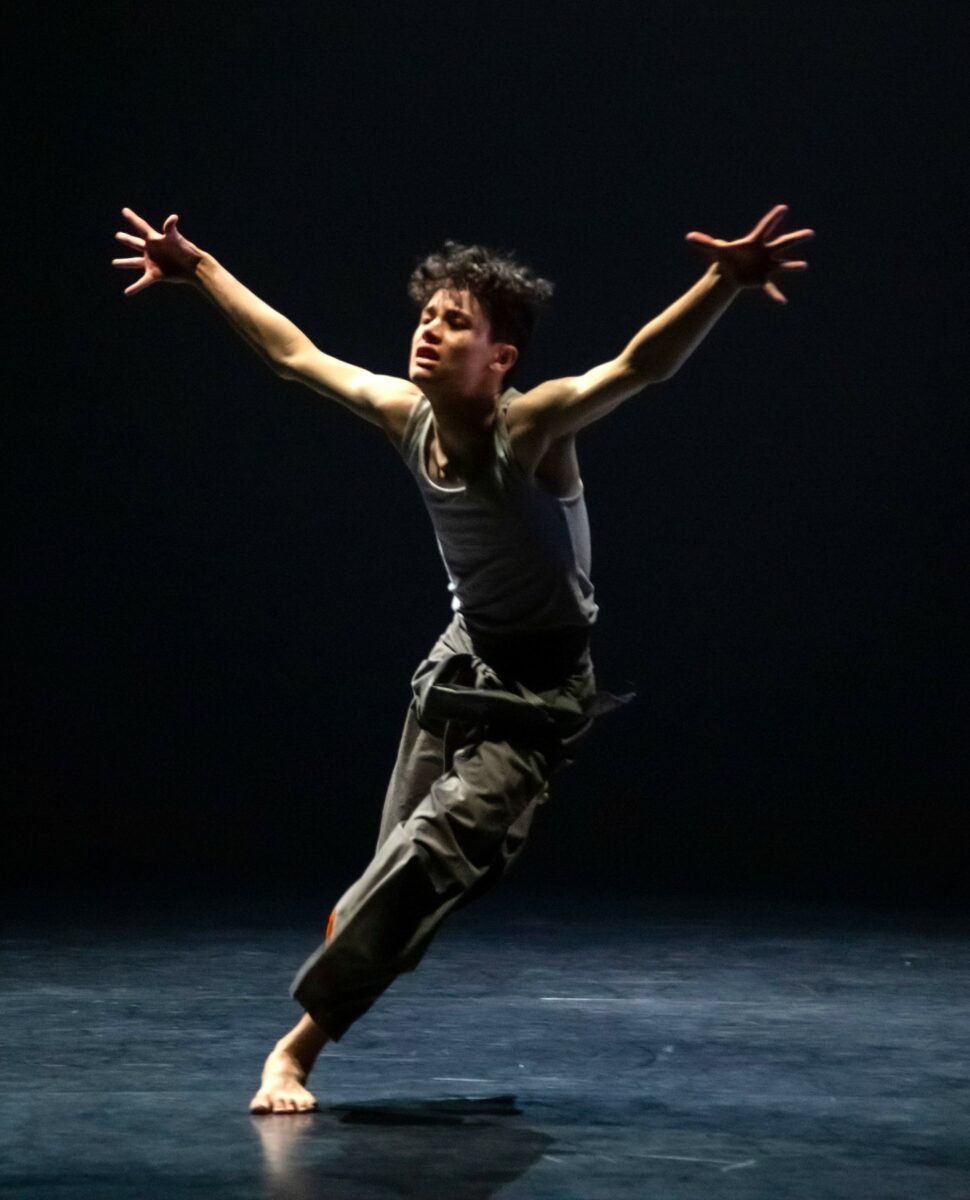

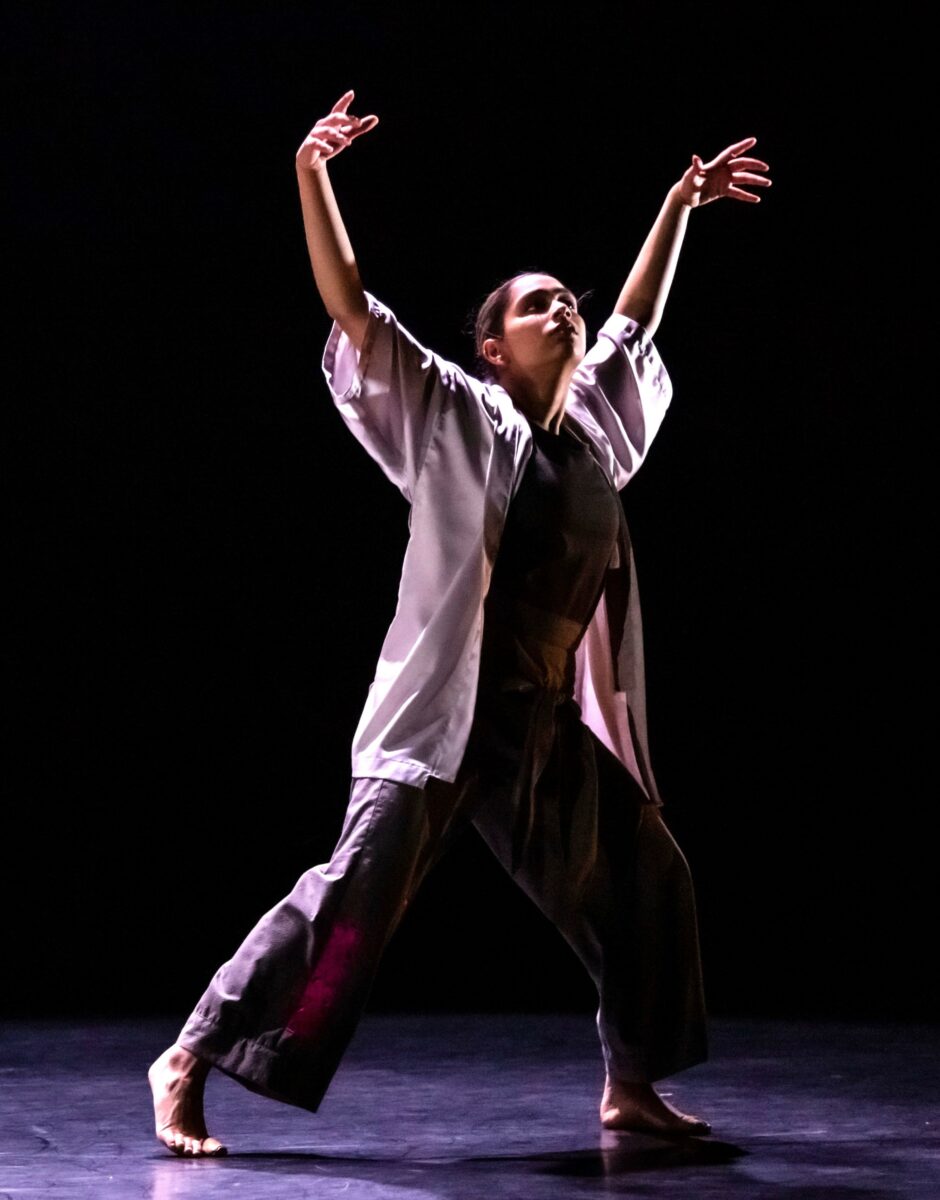

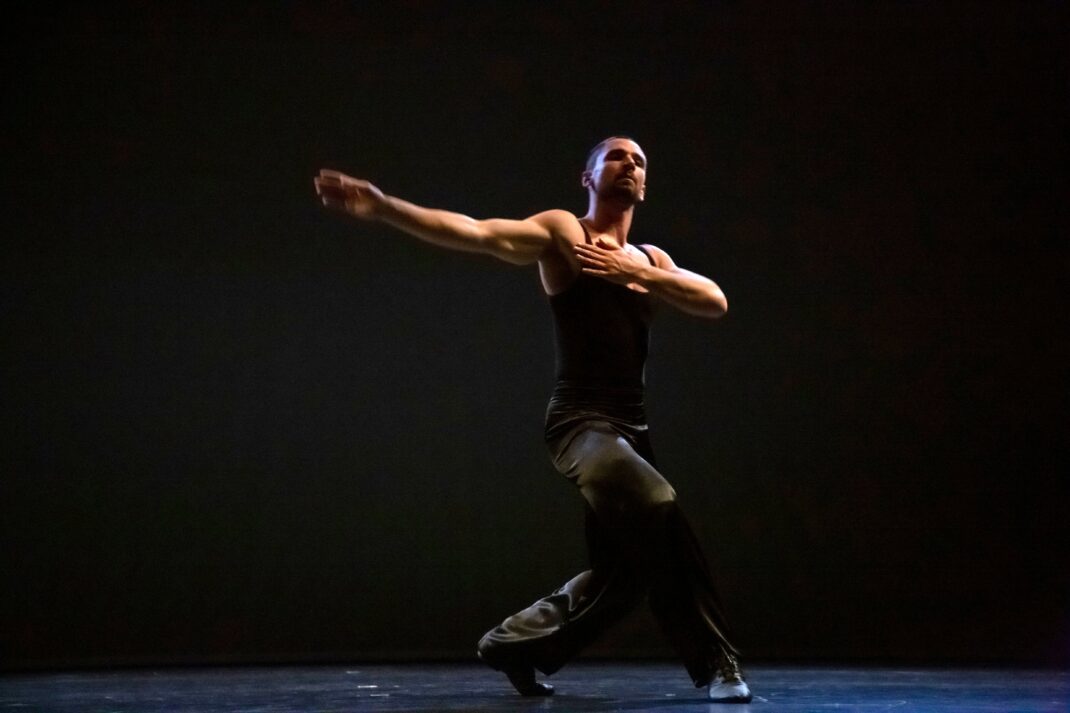

I was also mesmerised by the way Leskova moved when she was coaching dancers. This was especially noticeable in footage showing her coaching dancers of the Dutch National Ballet. At the age of 79, she wasn’t just demonstrating she was performing with her whole body, and it was easy to see that dance was an inherent part of her being.

Leskova turned 100 in December 2022. It is nothing short of amazing to watch this DVD, which is actually available on YouTube (but with no subtitles). Leskova’s career extends way beyond the Ballets Russes, for which she is so well known in Australia, and I have nothing but respect for her approach to performing, coaching and teaching. She has built a reputation for being demanding and several of those who appear on the DVD say she made them cry with her comments and demands. But the outcomes she achieved are exceptional, especially in her restaging of the ballets of Massine, which she did across the world.

The DVD closes with Leskova saying:

I was born in Paris. French people don’t take me as one. The Russians don’t take me as Russian. The Brazilians don’t take me as one. So, I am a ballerina. Free in the world.

A DVD well worth making the effort to watch. For more about Leskova on this site see this tag.

Michelle Potter, 13 June 2023

Featured image: Detail of Tatiana Leskova as a young dancer. Image from the DVD Tatiana Leskova. Nos passos de uma bailarina solta no mundo. Full image below. Photographer not identified.

Note: I was unable (for reasons unknown) to embed a link to the YouTube video of the Leskova DVD but it is easily accessible via a web browser.