Being in London is always full of dance surprises. Apart from performances, the city’s galleries almost always have a dance-related exhibition, or a small display featuring dance items from their permanent collections. This November, for example, the Courtauld Gallery had a particularly interesting show, Rodin and dance. The essence of movement. It examined Rodin’s mouvements de danse, until now a little known a series of sculptures, with accompanying drawings, made towards the end of his life.

The first room of the exhibition had a section that looked at the inspiration Rodin drew from the visit to France by the Royal Cambodian Ballet in 1906, which I have discussed briefly in a different context elsewhere on this site. This room included a small number of the very beautiful drawings in pencil, watercolour and gouache that Rodin made of the Cambodian dancers, along with photographs of contemporary dancers who also influenced Rodin, including Loïe Fuller and Ruth St Denis, and some photographs of Rodin himself.

The second, and main room contained material devoted to the mouvements de danse, a collection of terracotta and plaster figures, with some bronze castings, and accompanying drawings showing extreme dance movements and acrobatic poses. Although the drawings had been exhibited during Rodin’s lifetime, the sculptures had not. While they were all fascinating to look at—and there is a handsome exhibition catalogue (Rodin and dance. The essence of movement (London: Paul Holberton, 2016)—a model of Vaslav Nijinsky (in fact two models, one in plaster and one in bronze) attracted my attention.

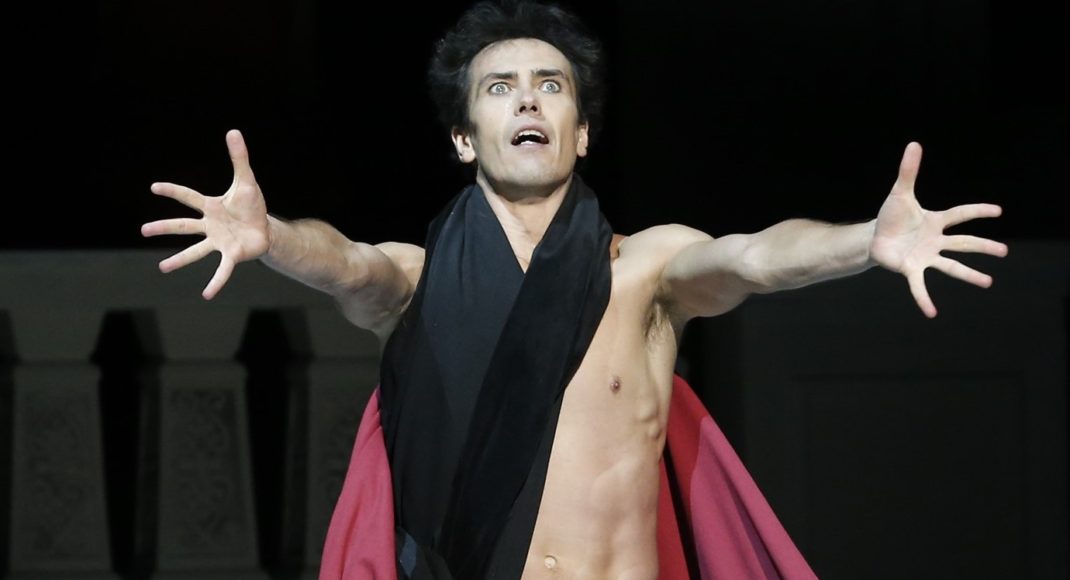

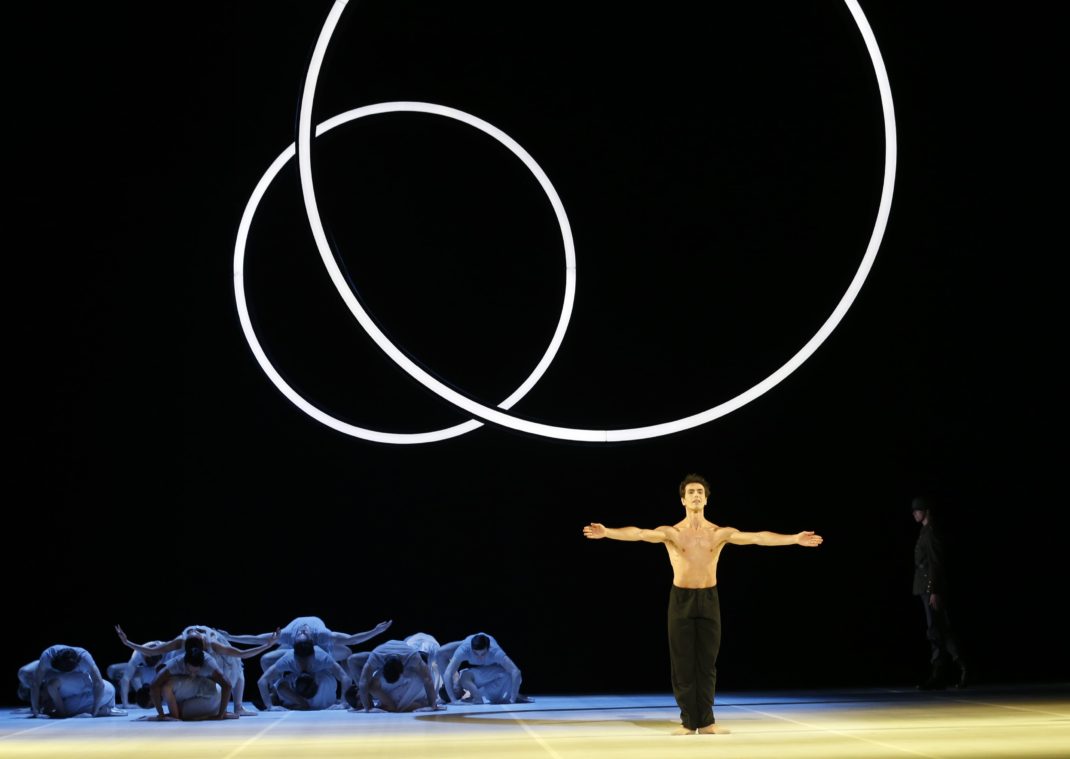

Rodin is known to have been at the opening night of Nijinsky’s L’après-midi d’un faun in Paris in May 1912 and followed up with an article in the Parisian newspaper Le Matin in which he showered Nijinsky with praise. Shortly afterwards, Nijinsky reputedly visited Rodin in his studio when it is thought the model for the sculpture was made. Looking at the sculpture it is impossible not to notice a certain turbulence and intensity in the figure. It is quite breathtaking in fact.

The Courtauld also has a collection of bronzes and paintings by Degas including the one shown as the featured image in this post. This particular bronze made me wonder about how it was made. Did a model pose, and if so was she a dancer? Most dancers, I think, would automatically take a pose with the lifted arm in opposition to the pointed foot, rather than same arm as leg as in the sculpture. Or did Degas simply model from memory, or just by adding body parts unthinkingly? But however it was made, this sculpture looked particularly beautiful as a shadowy figure with light streaming through the window.

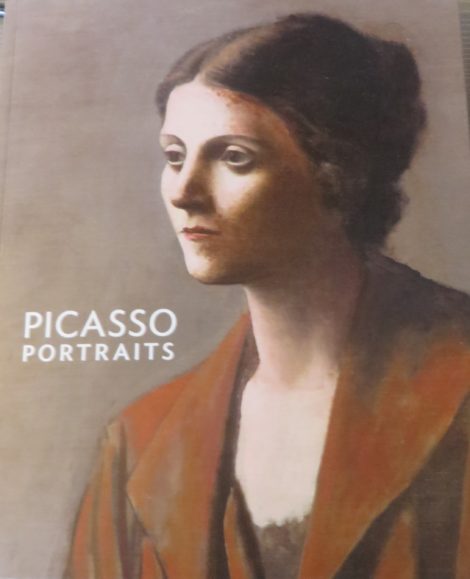

The other major show with a strong dance component was an exhibition, Picasso Portraits, at the National Portrait Gallery. One room was devoted to portraits and some photographs of Picasso’s first wife, Diaghilev dancer Olga Khokhlova. While the portraits and drawings were fascinating, so too were some photographs of Olga, including two of her on the roof of the Minerva Hotel in Rome and some wonderful home movie footage of the family—Picasso, Olga, their son Paulo, and the family dog enjoying some light-hearted family moments.

A portrait of Olga appears on the cover of the catalogue (Elizabeth Cowling, Picasso Portraits (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2016).

Other rooms in the Picasso Portraits exhibition contained items relating to Ballets Russes personnel including composers, designers and of course Jean Cocteau looking particularly dashing in one pencil drawing in two dimensional, Egyptian style representing, so the caption said, Cocteau’s well known vanity.

Michelle Potter, 12 November 2016

Featured image: Edgar Degas, bronze sculpture of a dancer, right foot forward, the Courtauld Gallery, London. Photo: Michelle Potter