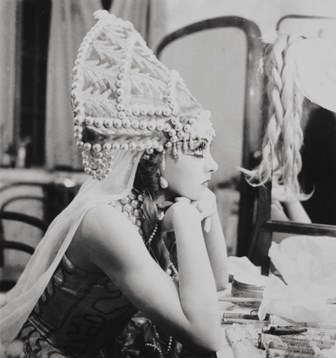

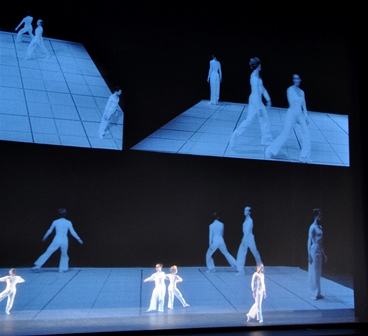

6 December 2014 (matinee), Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

There is a lot to like in Peter Wright’s version of The Nutcracker, the Australian Ballet’s final show for 2015. But once again the stage of the Joan Sutherland Theatre showed its inadequacies as an opera/ballet venue. What a squash it was at times!

I admired in particular the logic that Wright has introduced into the story, including the expanded role played by Drosselmeyer, admirably performed by Rudy Hawkes whose sense of drama and onstage presence in Act I was exceptional. I also admired that elements in the mysterious happenings after midnight in Act I (scene ii, although not referred to as such in the synopsis) are prefigured earlier in the unfolding of the story. And I enjoyed too that Clara takes on an active part in Act II.

Most of John F Macfarlane’s costumes are a delight to the eye, especially that red dress worn by Clara’s mother, and the Jack-in-the-box costume with pants that look like they are made from expandable metal or wire. I’m not sure though about that musk-stick-pink doublet worn by the Prince in the Act II pas de deux—it did nothing to add a princely look, although I guess it was appropriately lolly-like. Macfarlane’s sets for Act I are also attractive, but those over-decorative elements in the Act II set, including a large bright sun and those huge, red flowers do not sit well with the pink marble columns, although the columns themselves are lovely. Perhaps the Act II set looks better on a bigger stage?

In the performance I saw, Karen Nanasca danced Clara and was impressive from the first moment she appeared. Her charm and sense of wonder at what was happening as the ballet progressed were appropriately youthful and quite beautiful. She has such lovely arms and a technique that just needs a little more strength to carry her through some of the more difficult movements. The other standout was Thomas Palmer, a young Sydney-based dance student who played the part of Fritz, Clara’s little brother. Apart from the fact that he danced well, his acting and his ability to engage with the audience were superb. In the cameo roles of the Grandmother and Grandfather, Kathleen Geldard and Colin Peasley were a delight and all in all the dancing throughout Act I was first-rate. Benedicte Bemet and Christiano Martino made a wonderful Columbine and Harlequin, while Simon Plant and Marcus Morelli danced with panache as the Jack-in-the-box and Drosselmeyer’s assistant respectively.

Act II, however, was a different matter. Sadly, what should be the highlight—the grand pas de deux—was a bit of a let down. I felt there was no emotion between Kevin Jackson as the Prince and Miwako Kubota as the Sugar Plum Fairy, although Jackson was trying to make something happen. But there was no sense of excitement, no sense of the thrill and the splendour of the choreography. Very frustrating. There were also some unsettling moments, especially in the Russian and the Arabian Dances when the gentlemen seemed to stumble around a few too many times. And there is no excuse for ribbons on pointe shoes to come untucked as they did, very obviously, on the shoes of one dancer.

Despite these grumbles a traditional-style Nutcracker is always a treat at Christmas time. At least in the first act I was transported. It was lovely too to see a lot of children in the audience, including one behind me who whispered loudly to her parents when the toy nutcracker’s head was ripped off and the doll was lying on the floor in two pieces, ‘Oh, I hope he will be all right’.

Michelle Potter, 7 November 2014

Featured image: Artists of the Australian Ballet in The Nutcracker, 2014. Photo: © Jeff Busby