21 May 2025. Screened at the German Film Festival, Palace Electric Cinemas, Canberra

Cranko is quite a long film, over two hours. But it has such an engrossing narrative, as well as being a superbly realised production, that those two and a bit hours absolutely raced along. The film held one’s attention from beginning to end.

Directed and written by Joachim Lang, Cranko is, to use the media description, a ‘biopic’ of John Cranko, South African-born dancer and choreographer who directed Stuttgart Ballet from 1961 until his premature death in 1973. We are given brief information about his early life and aspects of his pre-Stuttgart dance career in England, but the film centres on his career with Stuttgart Ballet, a career that sees him engage, as both director and choreographer and even friend, with the artists who created for the company, including not just dancers but administrative personnel, designers, composers and others.

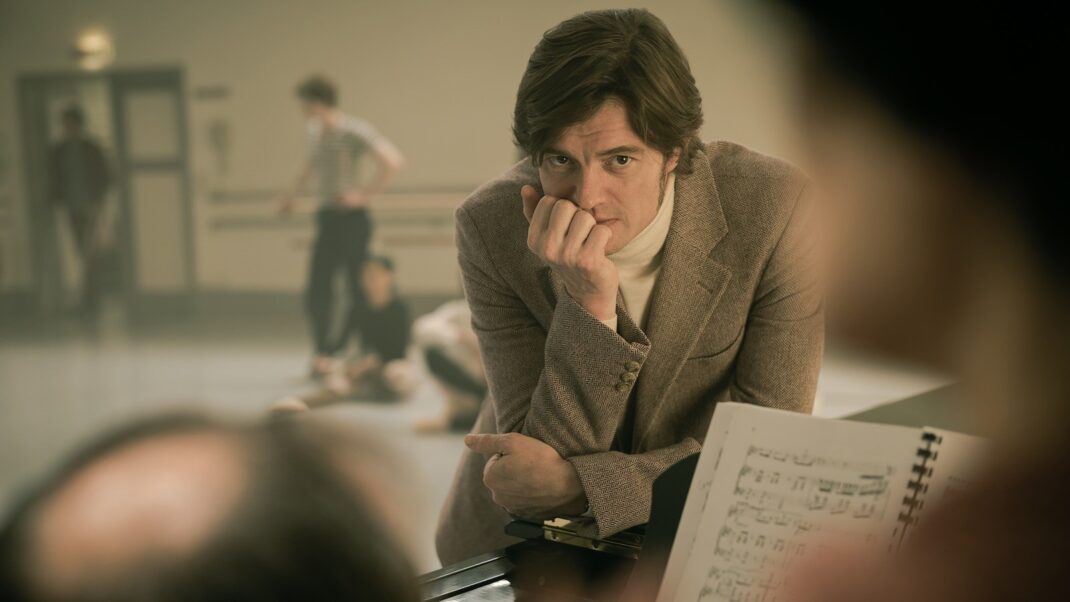

The ‘engagement’ was filled with all kinds of behaviour from Cranko. His personality was quite varied: he shouted pretty much at the drop of a hat, for example; he ignored standard procedures like ‘no smoking’ signs; he loved and there were a number of aspects of loving for him; he drank to the extent of being an alcoholic; he was at times overcome by depression and we were made aware of his attempts at suicide; and more. But basically he cared about dance. We see it all and his personality is brilliantly portrayed by Sam Riley, the actor who plays Cranko.

The action largely takes place in the studios of Stuttgart Ballet and its surrounds although we are taken to New York and the Met on a number of occasions when the company had engagements there. The dance component is stunningly danced by artists of the present day Stuttgart Ballet and the dance happens on many occasions and at times in unexpected ways. There are several sections from Romeo and Juliet and Onegin and I was especially delighted to see excerpts, filmed outdoors on a park bench, from The Lady and the Fool, a ballet I haven’t seen for many years. Perhaps most outstanding of the dancers was Elisa Badenes who played the role of Marcia Haydée, a major star of Stuttgart Ballet during the Cranko era and beyond. But the dancing throughout was just superb from the entire dancing cast.

Cranko’s death on board a plane returning Stuttgart Ballet personnel from the United States to Germany is perhaps the most frustrating part of the film. Cranko takes a sleeping pill but doesn’t wake up and is mourned by those on board and by the people who meet the plane when it lands. But we don’t really get any idea of what happened. Was it that pill?*

But there was a truly moving section at the end as the credits began. The original artists, whose life with Cranko was examined in the film, appeared (where that was possible) alongside the current dancers—Marcia Haydée stood next to Elisa Badenes for example. Just so moving.

Cranko is a spectacular film. I can’t wait to see it again—somehow.

Michelle Potter, 22 May 2025

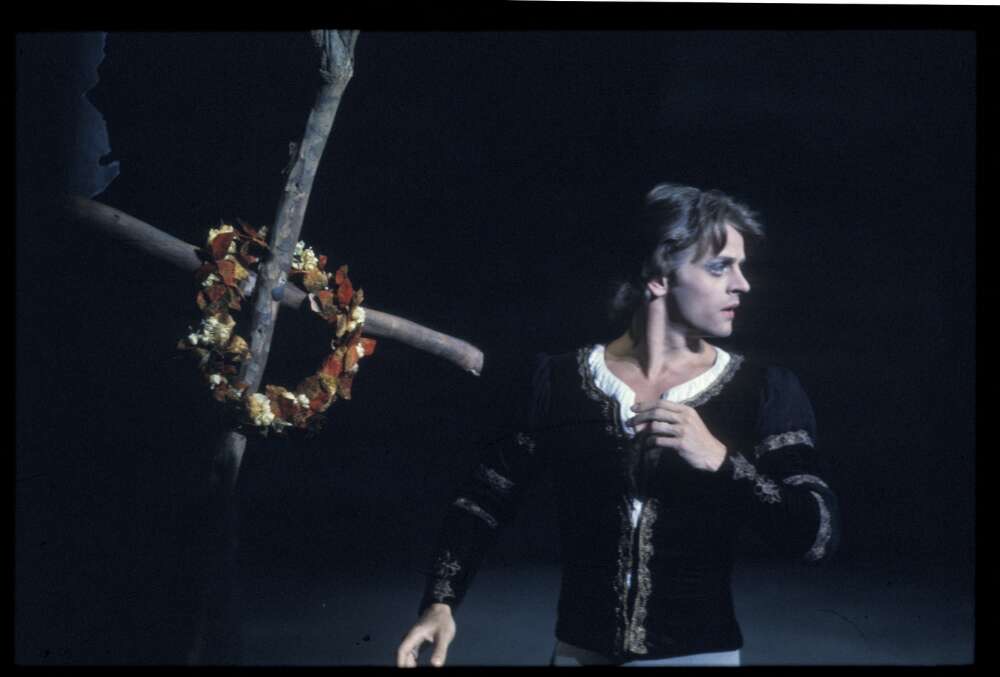

Featured image: A still from Cranko showing Sam Riley as Cranko

* After a bit of research I found that the plane had been diverted and had landed in Dublin where hospital attempts (unsuccessful) were made to reverse the situation. Later a Dublin-based Coroner made the following statement: ‘Mr. Cranko had taken chloral hydrate, a drug prescribed by his phyiicians, and the amount he took was nowhere near a fatal dose. Death was due to asphyxia by stomach inhalation while under the hypnotic effect of the drug, the coroner said. “This was an accidental death,” he declared.’