25 August 2016, Nishi Building, Canberra

Strings Attached, the debut show from Canberra’s new contemporary dance company, Australian Dance Party, is a knockout. The concept behind the show, devised by the ‘Party Leader’, dancer Alison Plevey, sounds simplistic: an investigation of the relationship between music and dance in a collaboration between four dancers and six musicians from the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. But as developed in performance it was totally engaging, illuminating and just plain exciting to watch.

The show began with the sounds of breathing, gentle at first but gathering volume as dancers and musicians met in the performing space before taking their positions to begin the show proper. ‘Before people spoke, we moved,’ the program states. ‘We moved to the innate rhythm of our hearts, our breath and the patterns of our lives.’ And so the dance and its musical accompaniment began, starting with some improvised movement and accompanying sound, moving on to a gentle piece with music by Jean-Baptiste Lully and a kind of slow and refined dance for all four dancers. The show continued its pathway through different musical and dancerly episodes—a lament, a tango, on to Jimi Hendrix with the dancers hooked up to iPods, and, finally, to an ‘Electronic Piece’ that became a riotous party/disco dance in which the audience was encouraged, and sometimes specifically invited to participate.

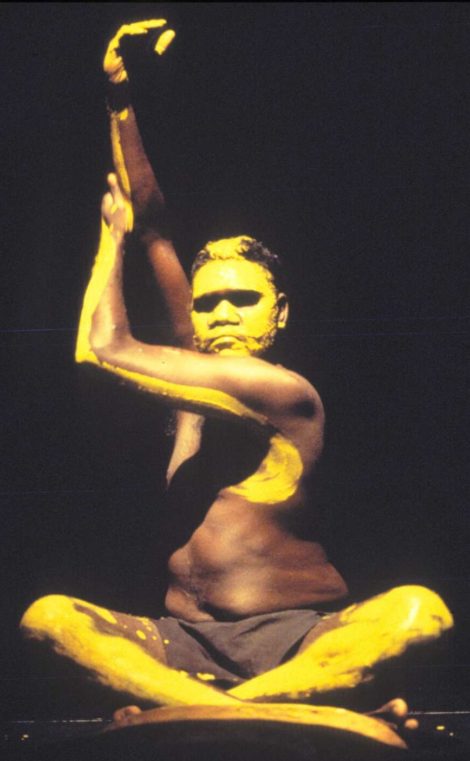

What was especially noticeable throughout was the absolute commitment of dancers and musicians. They were totally engaged with each other and with the sound and movement they were producing. Alison Plevey and Janine Proost both showed exceptionally fluid, high energy movement, Liz Lea was somewhat more restrained but added a way of engaging socially with the musicians that the others didn’t quite have—Lea always uses strong facial expression as a way of engaging. As for Gabriel Comerford, whose dancing I had never seen before, he knocked me for six with his movement that was on the one hand highly disciplined but on the other totally free.

The venue, a pop-up space in Canberra’s trendy Nishi building, was set up a little like a theatre restaurant with tables and chairs placed around a central performing area. Around the edge of the performance space the musicians sheltered under two white canopies of string sculpture crocheted by installation artist Victoria Lees.

Some particular highlights, personal favourites perhaps:

- Alison Plevey and harpist Meriel Owen improvising in the early stages of the show. Amazing, especially in the second part where Owen had to follow Plevey’s rising and falling movements, which she did as if it were second nature.

- Gabriel Comerford in ‘March’ (‘Command and Conquer Red Alert Theme—Soviet March’), in which he got totally lost, trance-like, dancing to a stirring, politicised composition by James Hannigan. His long, black hair came loose from its topknot, and his movement was at times absolutely precise and powerful, but at others wildly erratic. Thrilling to watch.

- A ‘conversation’ between dancer Liz Lea and trumpeter Miroslav Bukovsky.

- The musicians who played more than one instrument throughout, swapping seamlessly between them. And fascinating to look at (as well as to listen to) was Tim Wickham’s white ‘skeleton’ electric violin.

But in many respects it is unfair to single out individuals because everyone in this show gave so much of themselves to make this a standout evening of live music and dance.

I guess my one hope for this brave new venture is that the format of the debut show will not always be the format in the future. Plevey has a rare intelligence as a director and I hope she will find ways of occasionally presenting her work in different spaces, including in more mainstream performing arenas. The party line (as in its celebratory rather than political meaning) is fine for a start but I am hoping for something different as well.

Canberra has been without a professional dance company since Sue Healey left town in the 1990s. If Strings Attached is anything to go by we now have much to anticipate.

Michelle Potter, 27 August 2016.

Featured image: Dancer Gabriel Comerford and cellist Alex Voorhoeve in Strings Attached, Australian Dance Party, 2016. Photo: © Lorna Sim