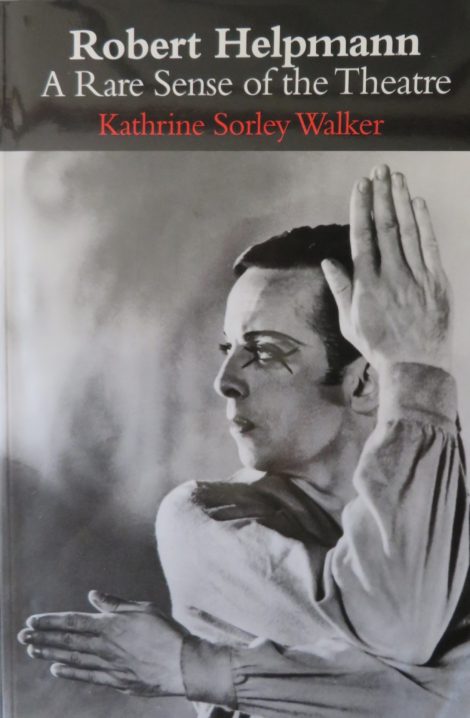

‘Mim’. A personal memoir of Marie Rambert: Brigitte Kelly (Alton: Dance Books, 2009). Available in Australia from Footprint Books or any good bookseller.

Marie Rambert, or Mim as she was familiarly known, brought her company, Ballet Rambert, to Australia in 1947. The company stayed until early 1949 and appeared in Adelaide, Brisbane, Broken Hill, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney with a short tour to New Zealand in May 1948. Astonishingly, they gave over 500 performances during those fifteen or so months.

Australian newspapers of the time refer to Rambert as a dynamic and somewhat unusual woman and it is clear that she enjoyed playing to the press. One clipping in a scrapbook held in the National Library of Australia shows her in a balletic pose supported by the entrepreneur Benjamin Fuller. He, somewhat portly, looks a little embarrassed. She is in her element! So it is not surprising to read in Brigitte Kelly’s absorbing memoir, Mim, sentences such as ‘She was a loose canon likely to explode in any direction’.

Kelly writes in an easy style. It is anecdotal but full of information and it offers opinions but is not opinionated. Perhaps what comes through most strikingly is the way Rambert’s personality, and that of her husband Ashley Dukes, affected the growth of Ballet Rambert. Kelly writes: ‘The strength and weakness of Mim and Ashley lay in the fact that they wanted complete autonomy over their enterprises, an understandable wish since they could then keep control over the artistic standards they set themselves’. There were serious and ongoing consequences especially of a financial nature according to Kelly.

A jolt to the Australian story is that the company left for Australia hoping to pay off large debts with profits made on tour. They returned from Australia bankrupt. Kelly writes: ‘[T]he manager, Dan O’Connor, had disappeared taking all the money and somewhere along the line lost the costumes and scenery’.

But the book also opens up the story of Rambert in an affectionate way offering many insights that only a dancer who was personally close to the company and its directors can offer. Rambert’s career with Diaghilev is touched upon as well as her ongoing connections with Diaghilev dancers. Her life in France before moving to England makes intriguing reading. And of course the trials and tribulations of the early company from the perspective of someone who performed in those early works of Frederick Ashton, Antony Tudor, Andree Howard, Walter Gore and others of equal note is engrossing.

Mim is a beautifully personal book. A memoir. And well worth the read.

Michelle Potter, 10 December 2009

For more about Ballet Rambert in Australia see my article published in National Library of Australia News, December 2002.

Postscript:

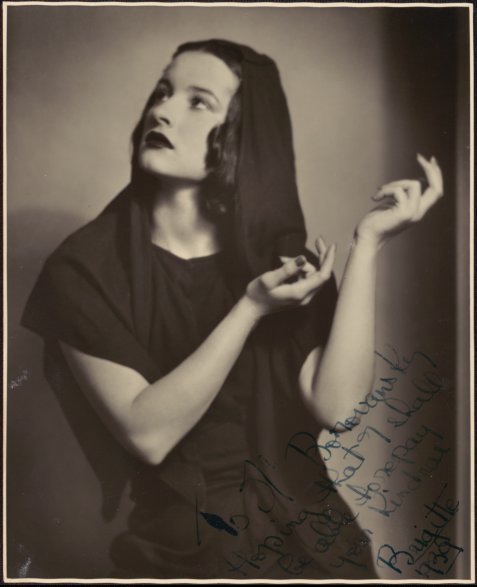

The author of Mim, Brigitte Kelly, came to Australia with the Covent Garden Russian Ballet on its 1938-1939 tour dancing under the name Maria Sanina. She speaks about the photo below, taken by Melbourne-based photographer Spencer Shier, in part three of her memoir ‘Dancing for joy: a memoir’ published in Dance Chronicle, 22, Nos 1, 2 & 3 (1999) saying that it represents her decision to model herself on film star Hedi Lamar. She writes ‘There was a photo call for the souvenir program. I dressed myself in the nun’s costume from the second movement of Choreartium, and when I look at the photograph the “look-alike” effect is really quite good’. (p. 362).