Don’t we need more than one Day?—how about a Week? New Zealand Music gets a Month. Let’s make it a Year for Dance…one day at a time.

by Jennifer Shennan

How was your International Dance Week? For me…

Day One—Saturday 29 April

I’m in Christchurch to see Woyzeck (which I’ve reviewed elsewhere on On Dancing)—a thrill to watch actors who move in such focussed ways, they could be dancers. Director Peter Falkenberg tells me later he works with Laban movement concepts for each actor’s character before they even get to the script. Aha, so that’s why these actors can dance.

That same day I meet up with three former students from New Zealand School of Dance — 1990s but I remember each of them very clearly, for different reasons, these three decades later. It’s heartening to hear their memories, and to learn about the enterprising ways they have since carved dance-related careers for themselves (dance teachers or Pilates tutors— the world needs more of both, so bravo)—but it breaks my heart to learn they are still carrying student loan debts of up to $60,000 from their student days! They don’t seem as fazed by the facts or the dollars as I am on their behalf, but I know I would feel crippled and unable to sleep, let alone work, let alone dance, if I was shouldering such a debt. It’s madness and has negative effects in several directions—e.g. a further colleague of theirs won’t come back to New Zealand on account of her loan, so grandparents don’t meet their grandchildren … another, with a young family, is back here but can’t get a mortgage to buy a house … another won’t take a job here since that would mean having to pay back the loan. Which political cynic choreographed this chaos of educational economics, this dance of death? [Of course we well remember which Minister of Education introduced the scheme, we just don’t want to speak his name. Australia manages a much better and fairer system apparently].

Those former students and I plan to set up a dance club around the Youth Centre that is soon to open in Christchurch. We’ll be offering 500 year old break dancing (that’s galliards to you—along with some pavans and brawls). All we know at this stage is that it will be free for participants and there will be live music. We can do this. Not all the youngsters will want to join in, but some of them will.

Day Two—Sunday 30 April

I spend the day in Christchurch with Ian Lochhead, dance writer and historian, and a trustee of the Russell Kerr Lecture in Ballet & Related Arts. We’re discussing suitable topics for next year’s RKL and thought we’d like to mark RNZBallet’s 70th anniversary in some meaningful way. We plan to canvas attendees widely, inviting their response to the question, ‘Which is your single standout memory of a production across the 70 years or so you’ve been watching this company? The work you recall as suiting the company uniquely and memorably?’ We’ll be intrigued to learn if our initial consensus as to which work is chosen will continue to find favour. The RKL will be a Sunday in late February 2024.

Day Three—Monday 1 May— M’Aidez.

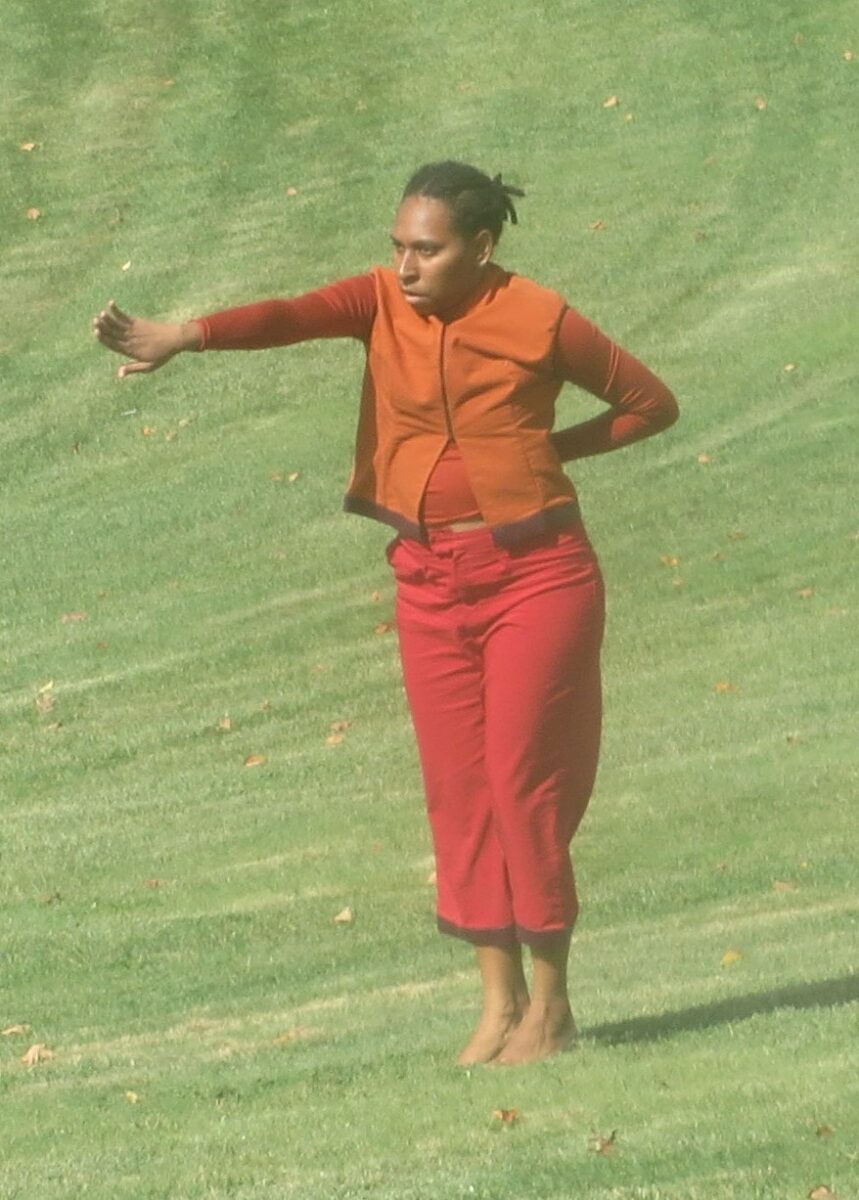

I walk on the grass and remember May Day in history … ‘the first day of May, long celebrated with various festivities, as the crowning of the May queen, dancing around the Maypole, and, in recent years, often marked by labour parades and political demonstrations.’ There’s an interesting entry on Alastair Macaulay’s website about the maypole in Black dance history. On Youtube in Ashton’s La Fille mal Gardée a maypole is sweet and colourful but doesn’t have the urgency that outdoor rituals can offer, and seems to taper off rather than triumph at the cadence. (The late Annette Golding, a dance educator at Wellington Teachers’ College, used to mount a very spirited Maypole on her students back in the day). I spend several hours reading the titles on the spines of Ian’s very considerable dance library. I appreciate an update on the May Day gala dance event being organised by Maryanne Meachen for a performance in Palmerston North.

Day Four—Tuesday 2 May

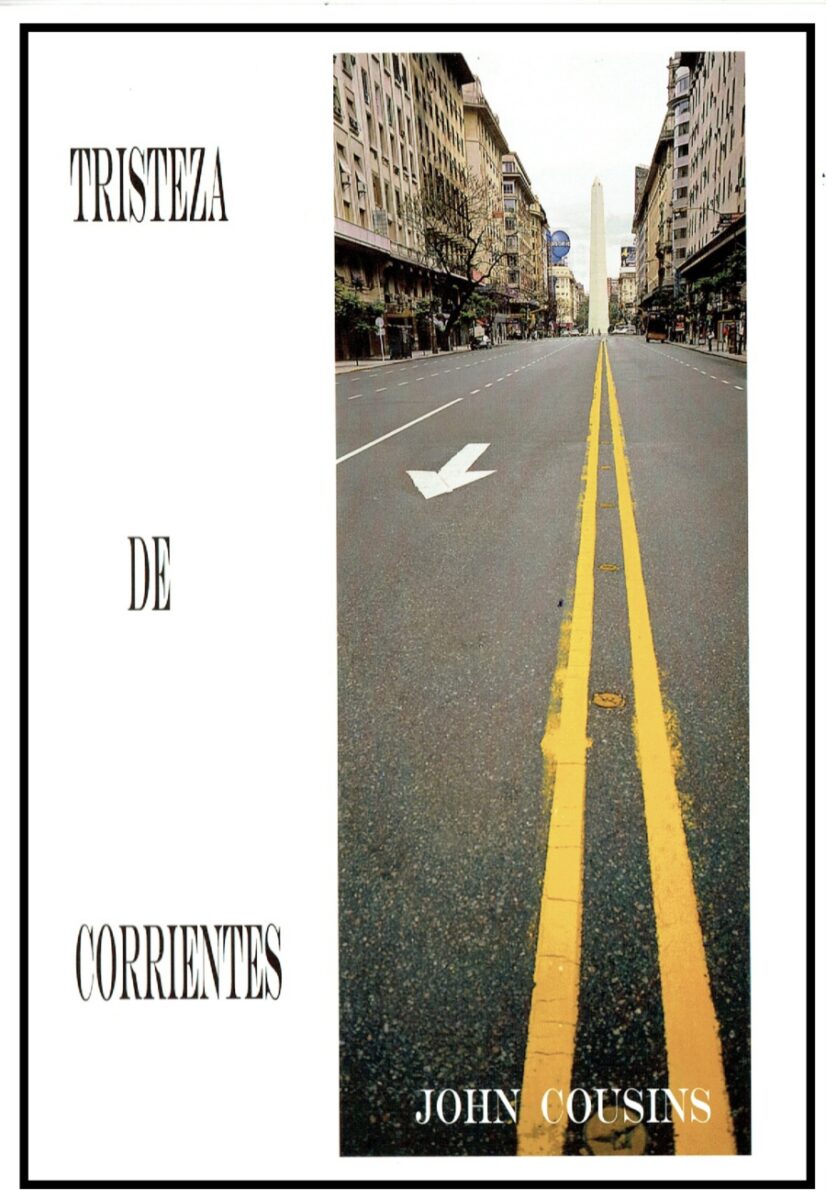

I stay with John Cousins, composer friend, and Colleen Anstey, dancer friend, both of them tango milongueros. They had travelled to Buenos Aires for a tango festivaI a few years back but found themselves undone to learn the stories of Argentinian struggles, sufferings, deaths and disappearances. I listen to John’s very moving composition Tristeza de Corrientes with accompanying images, on the subject, and remember how no dance is isolated from the context of its community.

Day Five—Wednesday 3 May

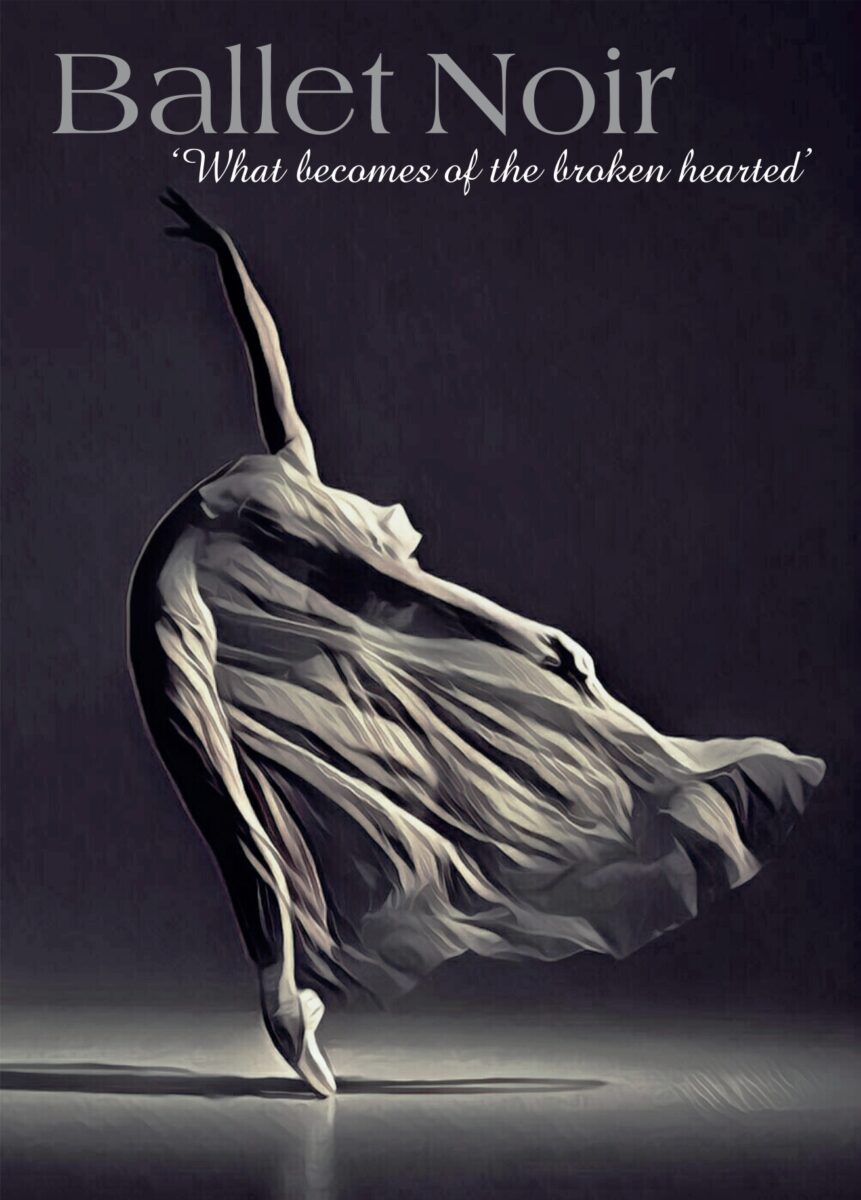

I return to Wellington, to view a filmed excerpt from Mary-Jane O’Reilly’s Giselle, which she has re-named What Becomes of the Broken Hearted? I sincerely hope MJ finds funding to complete the full-length theatre version, as this is a striking and spiky wonderful contemporary re-choreographing of a classic work that departs from, yet pays respect to, the original.

Day Six—Thursday 4 May

I teach a Baroque dance lesson to a new and fired student who keeps us going at an impressive pace, and doesn’t mind appreciators watching our work. Robert Oliver, the viol player who accompanies us, is a joy to collaborate with.

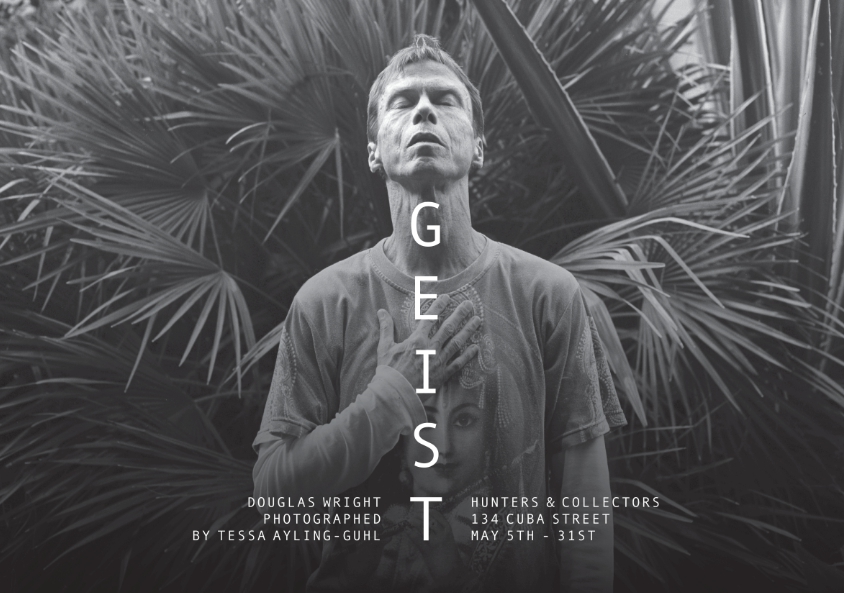

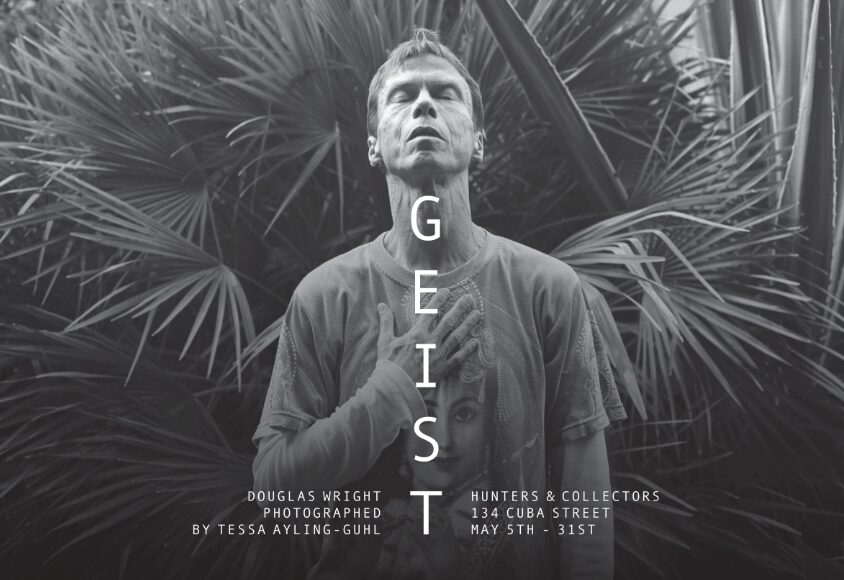

I then go to Hunters & Collectors gallery for the opening of the exhibition, geist, photographs of Douglas Wright, by Tessa Ayling-Guhl, taken in 2015, but never before exhibited. They are astonishing images of this visionary dance force. Even though Douglas died in 2018, the memory of him is indelible for many. A dance performance by Björn Aslund, with Robert Oliver, is being prepared to close the exhibition.

I then go to St. James Theatre for a performance of Romeo & Juliet by Royal New Zealand Ballet, choreography by Andrea Shermoly. The role of Juliet is danced by Mayu Tanigaito who gives a beautifully tuned performance … but the real hero of the night is the conductor of New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Hamish McKeich, who leads the orchestra through the mighty and much-loved Prokofiev score, as much drama in the music as ever on stage. Not two years ago Hamish suffered a debilitating stroke leaving him with one arm and one leg seriously affected. This annoyed him as there is much he still wants to do. Hamish conducts this mighty music using just one arm and takes his curtain call from side, not centre stage as the walking stick might slow things down. If that’s not courage then nothing is.

I am reminded of the Auckland-based Touch Compass mixed-ability dance company, founded and led for years by the gifted and intrepid Catherine Chappell. As one performance ended, curtain calls over, audience readying to leave, curtain still up on an empty stage, Catherine’s voice over, ‘Would the dancers go back and help clear the stage of the various props and set please’ … a voice replies, ‘Oh but I’ve only got one arm. ..’ Catherine replies, ’Then that’s the one to use, isn’t it.’ Indeed it is.

Day Seven—Friday 5 May

I attend the funeral of the much-loved Margaret Nielsen, pianist and champion of New Zealand composers’ work. Margaret died close to 90, ‘ready to go now as I’ve selected all the music I want at my funeral.’ Many beautiful songs later, came the excerpt from her colleague David Farquhar’s Ring Around the Moon suite—composed as incidental music for a play in 1953—the year of the Queen’s coronation, the ascent of Everest by Edmund Hillary, and the founding of New Zealand Ballet by Poul Gnatt. Harry Haythorne used this music to stage the 30th Anniversary Gala—in 1983—everyone from the Company and the School onstage, dressed in swirling blue and dancing every spirited beat. Poul entered last and strode down centre stage, purposefully stepping on the off-beat. When Edmund Hillary was asked what is the essential attribute of a leader, he replied, ‘Well, involve everyone in the team, but the Leader has to have a Plan B.’ Poul always had a Plan B.

Margaret had chosen the Waltz and the Tango from Farquhar’s music. I ask myself—What else is there?

I come home to watch the choreography of the royal procession of the Coronation, and was especially impressed by the troupe of musicians mounted on horseback, playing their instruments and guiding the horses with their ankles and heels. Look, no hands! And there were Black gospel singers who (nearly) danced inside Westminster Abbey. It’s been a while since anyone danced in that Abbey I think.

Every day is Dance Day. That was my Dance Week. How about yours?

Jennifer Shennan, 8 May 2023

Featured image: Poster for Tessa Ayling-Guhl’s exhibition of her photographs of Douglas Wright, 2023. Image courtesy of Tessa Ayling-Guhl