I have often wondered about Ninette de Valois’ 1946 staging of The Sleeping Beauty, which opened up Covent Garden after World War II. My interest was sparked after examining dance in wartime London while undertaking research for my 2014 biography of Dame Margaret Scott.* More recently I have been interested in Oliver Messel, who designed that 1946 production, given that Kristian Fredrikson, as an emerging designer in the 1960s, admired Messel’s work, and in fact some of his 1960s designs are indebted to Messel.** So, it was interesting to be able to watch a recent revival of the de Valois production, a revival staged by Monica Mason and repetiteur Christopher Newton, originally in 2006.

The streamed production was a performance from early 2020 and featured Fumi Kaneko as Aurora and Federico Bonelli as Prince Florimund. I had not seen Kaneko, a Royal Ballet First Soloist, dance before and for me the most startling feature of her dancing was her exceptional sense of balance. It showed itself throughout the performance and, in fact, was more startling outside the Rose Adagio than within it. I also admired her characterisation as the 16 year old Aurora In Act I. She was full of youthful joy and excitement, although I would have liked a little more contrast in her Aurora of the last act, which would have strengthened her overall performance. She was, however, absolutely enchanting in this last act in her solo variation from the grand pas de deux. Her beautifully expressive arms and hands, for example, told us of the process of her becoming an adult.

Bonelli is a dab hand at playing princely figures and did not disappoint. I especially admired the emotional quality he brought to Act II as a lonely prince looking for love. Then, as with Kaneko, his solo variation in Act III was beautifully danced with exceptional control of those assorted leaps and turns. In fact, the grand pas de deux was thrilling from start to finish. Of the other characters, Elizabeth McGorian was an outstanding Queen, full of love and then concern for her daughter, while Kristen McNally was an individualistic and highly theatrical and flamboyant Carabosse. Thomas Whitehead developed the character of Catalabutte well and Yasmine Naghdi and Matthew Ball showed off their excellent techniques as Princess Florisse and the Bluebird. I especially enjoyed Naghdi’s understanding of what is behind that particular dance, that is she is listening to the Bluebird teaching her how to fly.

But how things have changed since 1946, at least from where I stand. This production had so much more mime than what I am used to seeing. Has it been lost in later productions? If so, why I wonder because in the Royal Ballet production it made the story much stronger, and there were no problems in understanding what was being ‘said’. And there were moments when certain aspects of the story were opened up. We know that the King banned all spindles from his kingdom after Carabosse declared that Aurora would die from pricking her finger on such an item. But I can’t remember seeing a production where three village women, trying to hide their spindles, were brought before the King who wanted to execute them. Such moments fill out the story and give back the narrative to what is essentially a narrative ballet. I loved it.

All in all, and as ever, the Royal Ballet gave us an exceptional performance from every point of view.

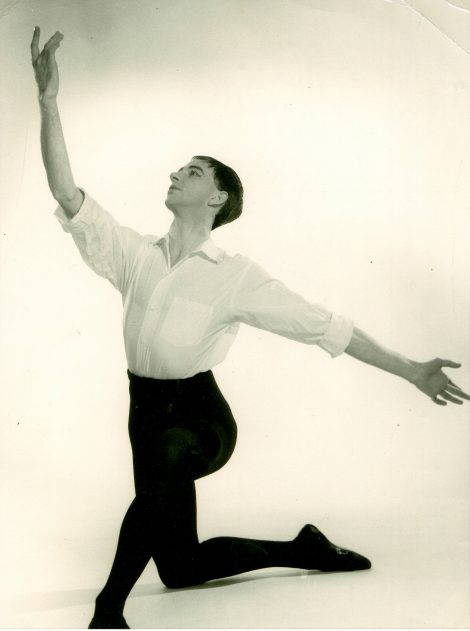

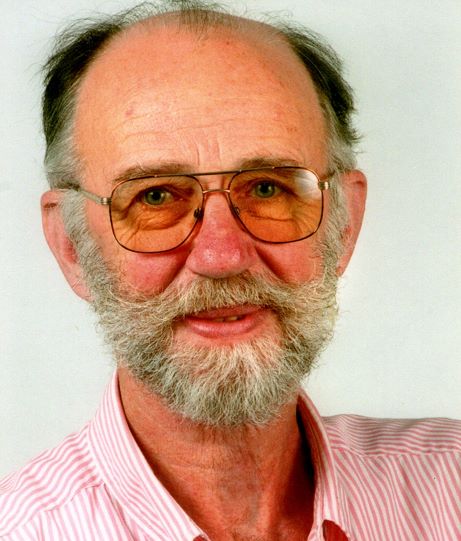

As for the Messel costumes, I thought many were just too much. Too much colour, too much decoration. I’m not sure why the Lilac Fairy had those bright pink layers of tulle to her tutu. It was only in the darkness of the forests of Act II that the glints of lilac could be seen peeking through the lolly pink. But it was interesting to see those characteristics of Messel tutus that Fredrikson picked up on in his early work—wide decorative shoulder straps, and an overlay of feathery (or leafy) patterns spilling down from the bodice onto the tulle skirt of the tutu, for example. This style was exemplified by the tutu for the Lilac Fairy (danced by Gina Storm-Jensen). Those few of Fredrikson‘s designs that are still readily available for Peggy van Praagh’s 1964 staging of Aurora’s Wedding, his first Australian Ballet production, show a similar approach. Fredrikson acknowledged his interest in Messel’s work when he said he admired Messel’s ‘extraordinary richness and imagination’.

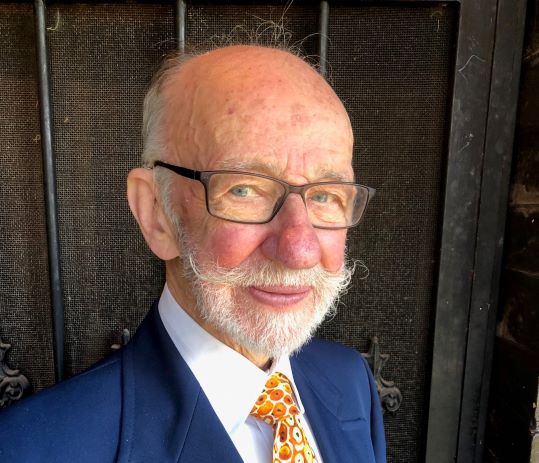

Michelle Potter, 29 July 2020

Featured image: Fumi Kaneko in a still from Act I, The Sleeping Beauty. The Royal Ballet, 2020

*Dame Maggie Scott. A life in dance (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2014)

**Kristian Fredrikson. Designer (Melbourne: Melbourne Books, 2020)