I have to admit that I shed a tear when I heard that Ronne Arnold had died. It was he who added jazz dance to my movement vocabulary when, aged about 17, all I knew was the vocabulary of classical ballet. His classes were an eye-opener and I especially loved the little routines on the diagonal that he would give towards the end of the class. He was a beautiful man and caring teacher and his impact on my life remains to this day.

Ronne Arnold was born in Philadelphia—he maintained he was not sure of the year; it could have been 1938 or even 1939 he suggested at various times. His African American family was large (it included six older sisters) and everyone danced. His early teacher was Nadia Chilkovsky. At Chilkovsky’s Philadelphia Dance Academy he took classes in classical, modern, and primitive dance. He also attended the Philadelphia Musical Academy, from which he gained a B.A. in music, majoring in dance. Later he worked with Alfredo Corvino and other New York teachers.

Arnold first came to Australia for Garnet H. Carroll in 1960 to appear in the musical West Side Story in which he took the role of Jose, one of the members of the Puerto Rican gang, the Sharks. He arrived on a six month contract and fully intended to return to the United States. But at the end of the run of West Side Story he was offered a job in the Carroll production of The Most Happy Fella and stayed a bit longer. A bit longer turned into years, and then decades, and he eventually became an Australian citizen.

Arnold went on to teach jazz and modern dance in Australia, beginning at the studio of Joan and Monica Halliday in Sydney. His classes were conducted with a tambourine as rhythmic accompaniment. But the tambourine was minus its ‘jingles’ so the beat was more like that of a drum. His teaching was inspirational. Arnold asked for huge, space expanding movements and his classes were quite unlike what most Australian dance students had experienced before.

During the 1960s and 1970s Arnold choreographed the dance sequences for shows at Sydney’s famous nightclub/theatre restaurant, Chequers. At that time, international cabaret acts at Chequers included Dusty Springfield, Dionne Warwick, Sammy Davis Jr., Liza Minnelli and Shirley Bassey.

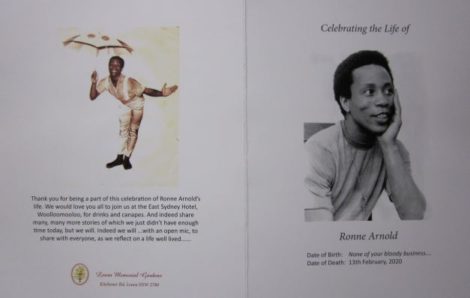

Arnold founded the Contemporary Dance Company of Australia in 1967 and was its artistic director until the company’s demise in 1972. The repertoire was choreographed almost exclusively by Arnold and included I’ve got Rhythm, New Blues, Boy with Umbrella, Feeling Good, and Song of Hagar to music by John Antill. Programs often finished with Spirituals, a collection of dances made to Negro spirituals, of which the crowd favourite was perhaps He’s got the whole world in his hands.

Slowly Arnold’s choreography began taking on an Australian flavour. He made Bittersweet about Australian male/female relations and Platform based on observations made at the Sydney Domain with its lively political spruikers. He also continued to appear in musicals and television shows throughout his life and his television credits included roles in Number 96 and Holiday Island and appearances in Cop Shop, and other shows.

Arnold’s teaching activities eventually came to encompass commitments at the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association (NAISDA College) in Sydney. He was academic course director at NAISDA from 1986 until 2003. Although Arnold had first become aware of Australia’s indigenous communities as a result of meeting political activist Bob Maza, once he began teaching at NAISDA he became fascinated by the visits to NAISDA of elders from indigenous communities. His interest resulted in a Master’s degree from Sydney University in which he undertook a comparative study of American black jazz dance and the dance of the Wanam people of Cape York Peninsula. On leaving NAISDA, Arnold taught for several years in Sydney at the Wesley Institute.

Arnold was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Australian Dance Awards of 2013. The award honours the achievements of an outstanding senior figure in the Australian dance community who has dedicated at least 40 years to dance as a performer, choreographer, advocate, educator, administrator or visionary. Ronne Arnold was all of those.

Arnold’s interview with Michael Cathcart on Radio National, recorded in 2013 in response to the award, is below.

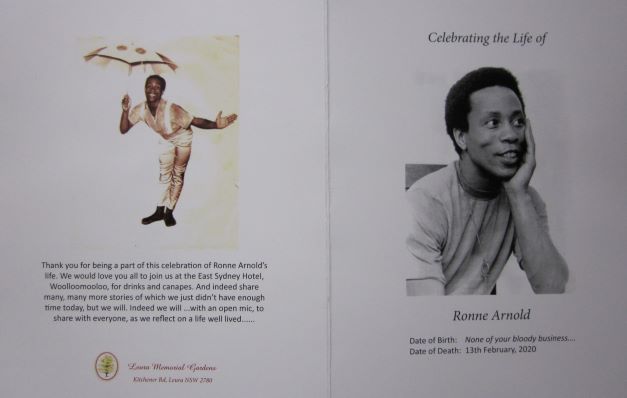

Ronne Arnold, born Philadelpdia, Pennsylvania c. 1938; died Katoomba, New South Wales, 13 February 2020

Michelle Potter, 23 February 2020

Featured image: Pages from Order of Service for Ronne Arnold. Courtesy Jan Poddebsky

This obituary is largely based on an oral history interview I recorded with Ronne Arnold for the National Library of Australia, TRC 3626, and on a conversation I had with him when writing about him for The Canberra Times in 2013. The oral history is not currently online and The Canberra Times article is no longer part of that newspaper’s online material.

Vale to Ronne Arnold – whose recent passing in turn evokes memories of Beth Dean Carell who told me about her production of Corroborree in 1970 when Arnold danced the lead role. I did not meet Ronne, but thanks to Beth’s dynamic account of him, always felt that I had.

Beth told me of Ronne’s interest in Laban dance notation, and I was interested to read in your profile that Nadia Chilkovsky had been his early and influential teacher in Philadelphia. Her own book, Introduction to Dance Literacy, is one of the clearest and most accessible introductions to the topic and I always felt it deserved to be more widely known and appreciated. Had it been used as an initial text to students of dance notation, I am sure it would have greatly increased the numbers of those who could see the value of a dance script to help in documentation and appreciation of important dance repertoire and movement rituals and traditions.

I first met Beth Dean ( and her husband Victor Carell) at the fortnight-long summer residential course designed and directed by Peggy van Praagh, held at the University of New England in Armidale, 1967, ( with a second one in 1969). Beth and I remained in lifelong contact, and became colleagues in a range of subsequent projects. I appreciated her generous spirit in sharing the joy and vitality of dance in Pacific contexts. Of her many publications, the book, South Pacific Art and Dance, co-authored with Bruce Palmer, then director of the Fiji Museum, remains for me the most resourceful ( in particular the footnotes to her enthusiastic text).

After all these decades, the most puzzling question that remains is not “What should one do to help document an ephemeral art practice?” (Beth, husband Victor Carell, and Ronne Arnold answered that by example in their many research and publication activities, as well as performing, choreographing and teaching of course ) but rather “Why were such inspirational and seminal courses of dance studies and appreciation not continued in perpetuity, at Armidale or elsewhere?” Rhetorical question maybe, but it still deserves an answer.

May I here record my continuing gratitude to Beth Dean, Victor Carell, and to Peggy van Praagh, for the visionary and encouraging ways they shared dance-related experiences. I can imagine that trio now enlarging their circle dance to include Ronne, which will make a lively lovely quartet that Botticelli would have been delighted to depict. Nothing and no-one ever dies completely.

Thank you for this comment. I have not had the occasion to read Nadia Chilkovsky’s book so you have whetted my appetite now! As for the Armidale Summer Schools, I was a participant at the 1976 school, which is where I first encountered in person Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon. Much later, an article on the schools appeared in National Library of Australia News. Here is a link to that article, which gives a bit of history and the reason why the program folded (the usual problem – no money!)

I first met Ronne when I was a mamber of the amateur Hurstville Musical Society. He was close friends with the Badder family who were involved both in professional productions and amateur shows. They invited Ronne to train some of the Society’s members, who were basically singers, to become more efficient in providing singers and dancers to perform more effectively in amateur shows. He was an inspiration to us all and he treated us all with respect, despite some of us having two left feet when we started. I last saw him at the funeral of Bill Badder, the father of the Badder family and, despite health issues, he was still the Ronne I remember from the 1970s. He will be remembered by all for his skills as a dancer, but also as a man with a great sense of humour.

Thanks so much for this comment Steve. It is great to hear your thoughts about Ronne’s activities. I hadn’t heard before about the work he did for the Hurstville Musical Society. His career was extraordinarily diverse.