In the final year of its legacy program, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company has just completed a season at the Joyce Theater in New York showing CRWDSPCR (1993), Quartet (1982) and Antic Meet (1958). This program not only spanned three decades of Merce Cunningham’s creative output, but it represented three major strands in his creative process.

The program moved backwards in time, although this was probably not a wise programming decision. Antic Meet, which closed the program, did not have the strength to bring the evening to a conclusion on a high note. It was, however, totally fascinating as representative of work from the early Cunningham period when money was short, the company was small and collaboration between three artistic giants—Cunningham, John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg—was a highlight of the company’s work. A series of slight unrelated moments for six dancers (four women and two men), Antic Meet is vaudeville, theatre of the absurd and a dada event rolled into one with the strength of the piece coming from the visual and musical accompaniments and the juxtaposition of sections rather than from the choreography itself.

Rauschenberg’s costumes, consisting of various additions to basic black tights and a black leotard, are an eclectic mix of ‘found’ items.

In one section the four women wear dresses originally fashioned from government surplus parachutes. The women are joined by a male dancer wearing a four-armed neckless sweater (made originally by Cunningham) and the sweater in fact becomes the dancer as it is swung, twisted, stretched and struggled with by the live dancer underneath its eccentric construction.

Others of Rauschenberg’s costumes include a fur coat (originally racoon), a long Victorian-style nightdress (both found by Rauschenberg in thrift shops), and some remarkably contemporary-looking black T-shirts with a plastic hoop inserted around the hemline—a little like very short, misplaced tutus. Along with a chair strapped to a dancer’s back, an assortment of props including a door on wheels that leads nowhere, and the accompaniment of John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra played live at the Joyce by five distinguished musicians, the whole is light heartedly bizarre.

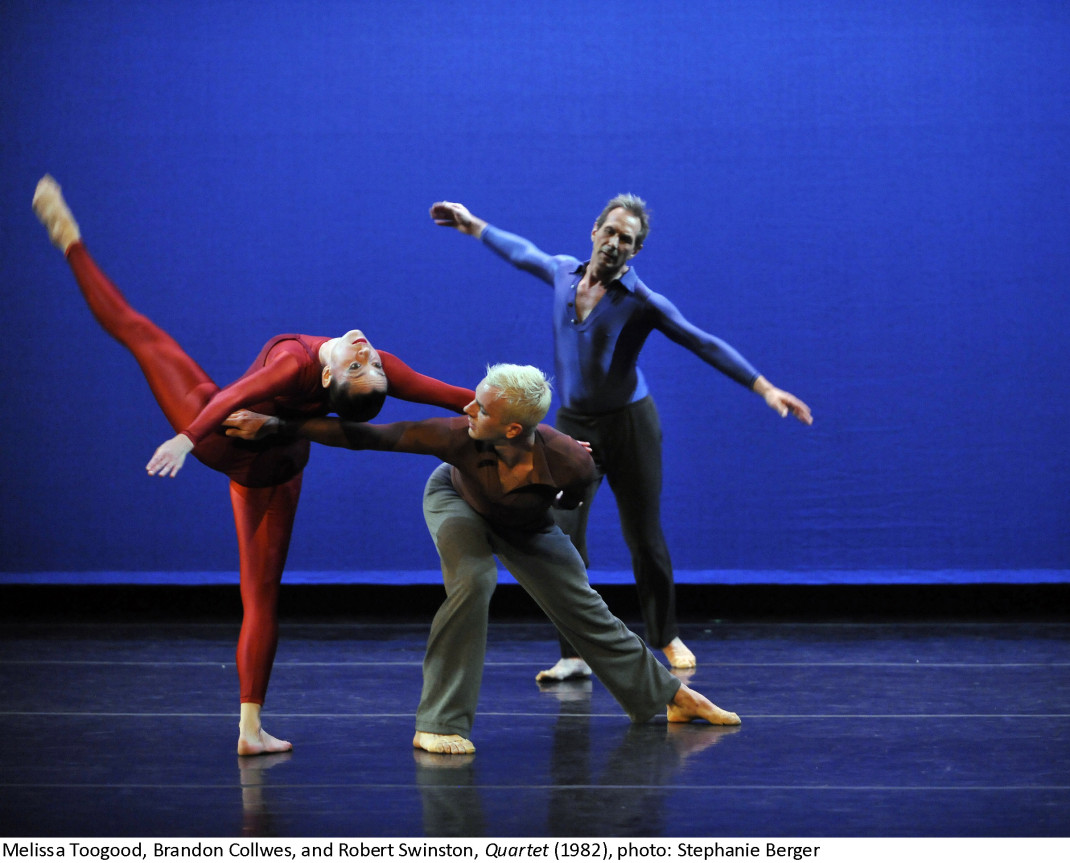

The middle piece, Quartet, is the most powerful of the three works on the program and represents Cunningham’s engagement with electronic music and with two major collaborators from the 1970s and onwards, designer Mark Lancaster and composer David Tudor. Although called Quartet, it was made for five dancers, a quartet who perform Cunningham’s signature choreography of off-balance poses, asymmetrical partnering and fast turns, and a fifth dancer who remains separated from the four and whose choreography is composed of twisted, sudden movements especially of the arms, largely made while standing on the spot. This fifth dancer was originally Cunningham and the work was created as arthritis was beginning to take its toll on Cunningham’s body. In the Joyce season the role was danced by the company’s current director of choreography, Robert Swinston. It is tempting to suggest that Swinston was posing as Cunningham. But he isn’t Cunningham and what Swinston was able to suggest was that Quartet is a work about belonging and not belonging.

With the dancers dressed simply by Lancaster in functional dance wear in luscious colours of olive, brown and burnished reds and blues, Quartet was performed to Tudor’s electronic score Sextet for Seven, played live by Takehisa Kosugi, the company’s current music director. Despite the theme of alienation and the somewhat chilling sound of the score, described as ‘six homogenous voices and one wandering voice’, Quartet is not a depressing work. In fact it seemed to me to be a very peaceful work as if in Cunningham’s mind the concept of outsider had been resolved.

The opening piece on the program, CRWDSPCR, is perhaps best summed up by a member of the audience who sprang to her feet as the work finished and shouted ‘Bit of work!!’ It is indeed a ‘bit of work’. It begins with its full complement of thirteen dancers on stage and for the twenty-five minutes or so that the dance lasts, apart from one slow solo section, the dancers weave themselves cross the space to John King’s electronic score, blues ’99. The energy is frenetic as the dancers manoeuvre past each other like the crowds at Grand Central Station, gathering momentum as they proceed. Pronounced either Crowd spacer, or Crowds pacer, a double edged notion that gives a clue to the nature of the work, CRWDSPCR is a little like ordered chaos but brilliantly designed choreographically and as brilliantly executed. The excitement it generated in the audience suggests that it would perhaps have been better placed at the end of the program.

CRWDSPCR represents Cunningham’s early but ongoing interest in using computer technology as a choreographic tool and he created it using the software program LifeForms (now DanceForms). It is costumed by Mark Lancaster in tights and leotards in fourteen blocks of colour to echo the software program. King’s score was again played live by King and Kosugi.

What a pleasure it was to see this this outstanding company in works from across the repertoire with music played live by such remarkable musicians. It was clear reinforcement of the vital role Cunningham, his company as it existed across many decades, and the astonishing collaborators with whom he worked, have made to the world’s dance culture.

Michelle Potter, 27 March 2011