Marquee TV is streaming for a limited time a ticketed program, for which I paid just over AUD 10, called Nureyev. Legend and Legacy. As a live show it happened in London early in September at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Reproduced to honour Rudolf Nureyev, it was directed by former Royal Ballet principal Nehemiah Kish and included works in which Nureyev performed, and some that he had restaged or choreographed for various companies. The dancers who appeared in the show came from various companies, with a strong contingent from the Royal Ballet.

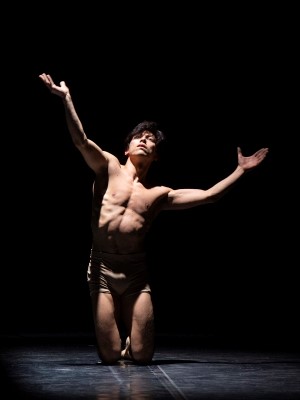

The program opened with the Entre’Acte solo from The Sleeping Beauty Act II, as interpolated into the ballet by Nureyev, as he did on other occasions in other ballets when he felt more choreography was needed for male dancers. Somewhat hesitantly danced by Guillaume Côté from the National Ballet of Canada, it made me feel that Nureyev was not such a good choreographer. The choreography seemed quite static and as a result the performance was a little underwhelming. But things got better and the dances that preceded interval included a lovely performance of the pas de deux from Bournonville’s Flower Festival in Genzano performed by Francesco Gabriele Frola and Ida Praetorius and the pas de six from Laurencia (which I had never seen before) showcasing an inspired Natalia Osipova and a dramatically stunning Cesar Corrales, along with Yuhui Choe, Marianna Tsembenhoi, Benjamin Ella and Daichi Ikairashi. The flamboyance of Laurencia with its Spanish flavoured choreography from Nureyev after Vakhtang Chabukiani contrasted well with the gentle beauty of Flower Festival.

The second half of the program included the grand pas de deux from The Sleeping Beauty performed by Natascha Mair and Vadim Muntagirov, a moving performance of the pas de deux from Act II of Giselle from Francesca Hayward and William Bracewell, and an excerpt from John Neumeier’s Don Juan danced by Alina Cojacaru and Alexander Trusch.

The program closed spectacularly with the pas de deux from Le Corsaire, a work that is undeniably connected to Nureyev’s astonishing career in the West. It was danced by the beautiful Yasmine Naghdi, whose work I have admired for a number of years, and the simply astonishing Cesar Corrales. In particular, Corrales’ solo demonstrated the extraordinary way he uses his body. He sweeps the floor at times as he leans into a step, but then reaches skywards at other times. His manège of grand allegro steps flies high and is perfection in performance, and his turns, in whatever position his legs are held, are just breathtaking in speed and execution. Then, the way he engages with his partner is thrilling, as is the pride he shows throughout in the way he holds his body. The coda was distinguished by brilliant dancing and a series of fouettés from Naghdi was filled with doubles, not just one every so often but often a single was followed by three consecutive doubles. My one complaint is that Corrales stretches his thumbs so that they look overly dominant. But astonishing work really from both dancers.

Australian audiences of a certain age were fortunate enough to see Nureyev perform in the 1960s and 1970s when he was here on various occasions. I can still remember his entrance in the pas de deux from Le Corsaire and the thrill that ran through my body even from my standing room position way at the back of the ’gods’ at the old Elizabethan Theatre in Newtown (Sydney). So watching this program, despite the odd moments that did not resonate well, was an absolute delight. And how I hope I will get to see Cesar Carroles perform live one of these days. He gives me the same thrill as I got from watching Nureyev.

Nureyev. Legend and Legacy, which includes short interviews with some who worked with Nureyev (including Monica Mason), is available on Marquee TV as a ticketed offering until 26 September only.

Michelle Potter, 21 September 2022

Featured image: Natalia Osipova in Laurencia pas de six. Photo: © Andrej Uspenski