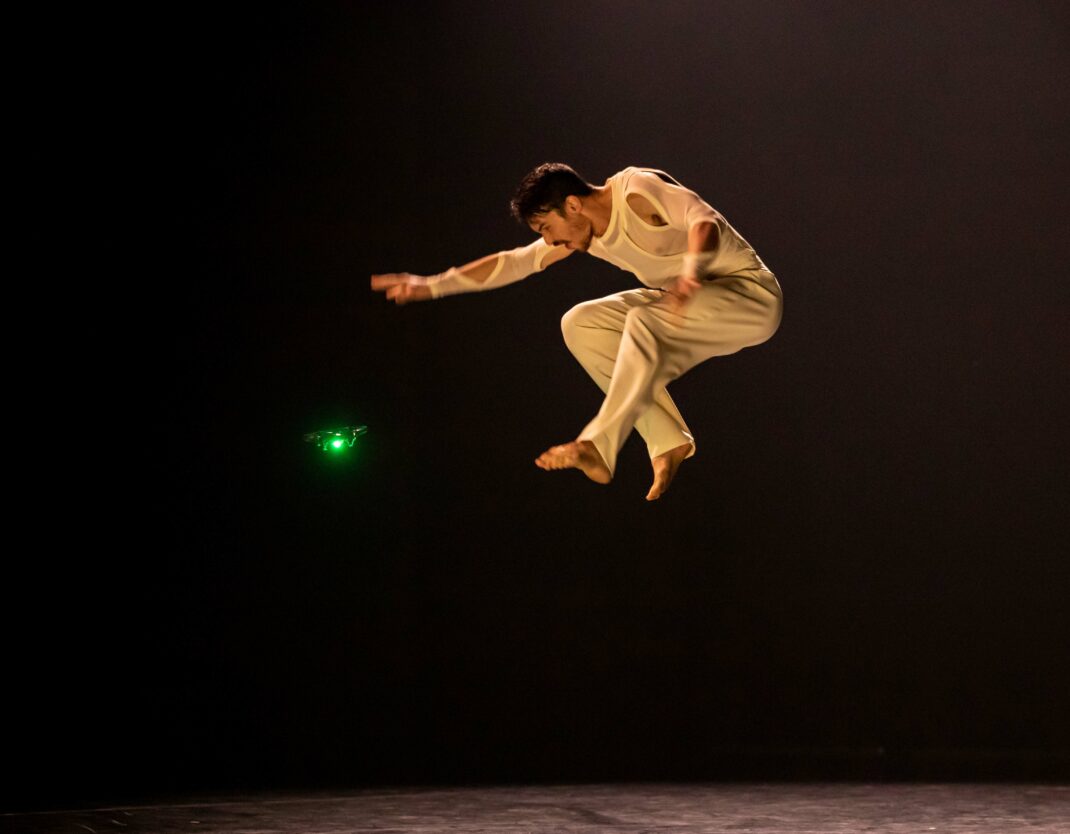

29 July 2023. Erindale Theatre, Canberra

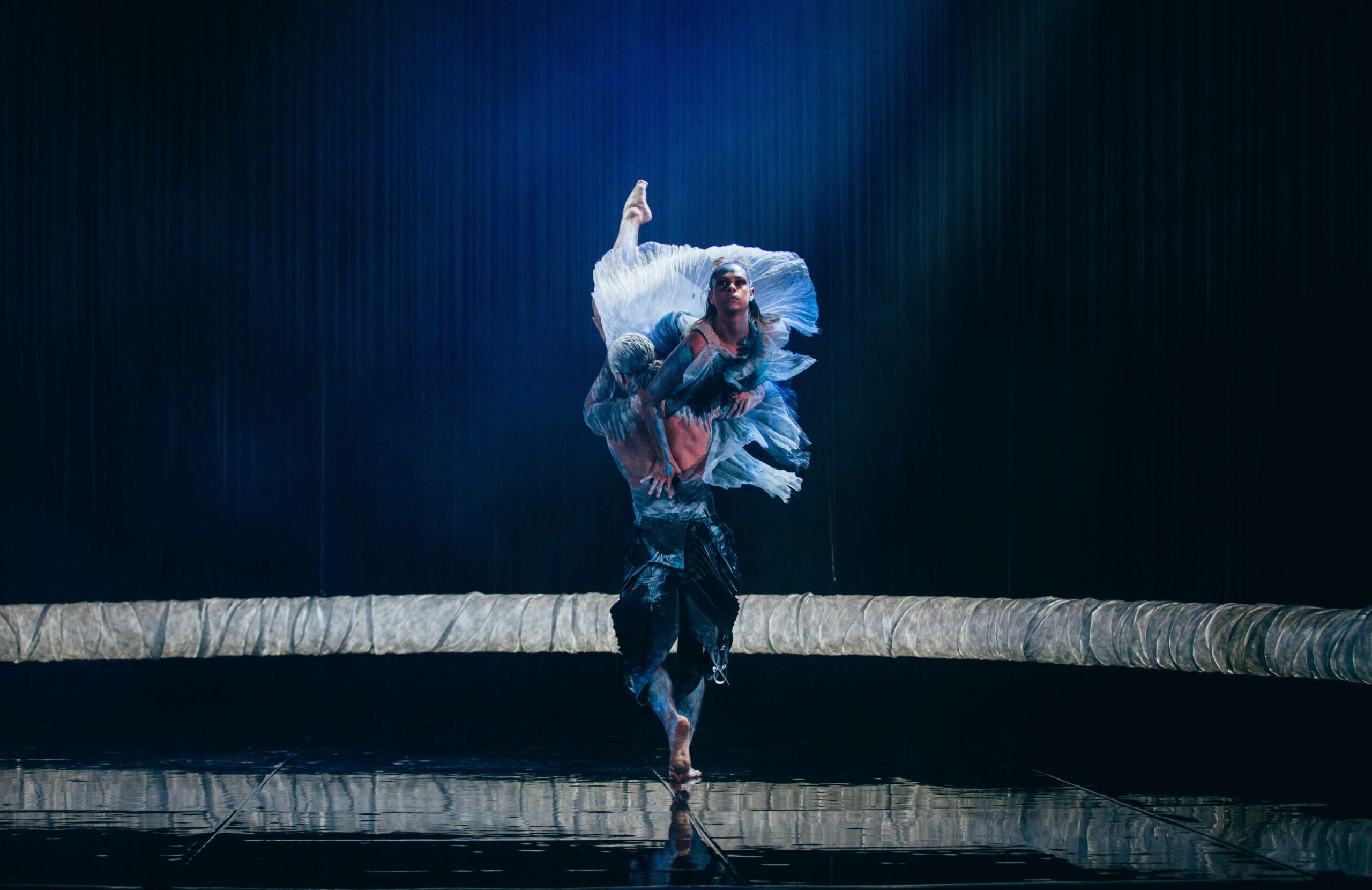

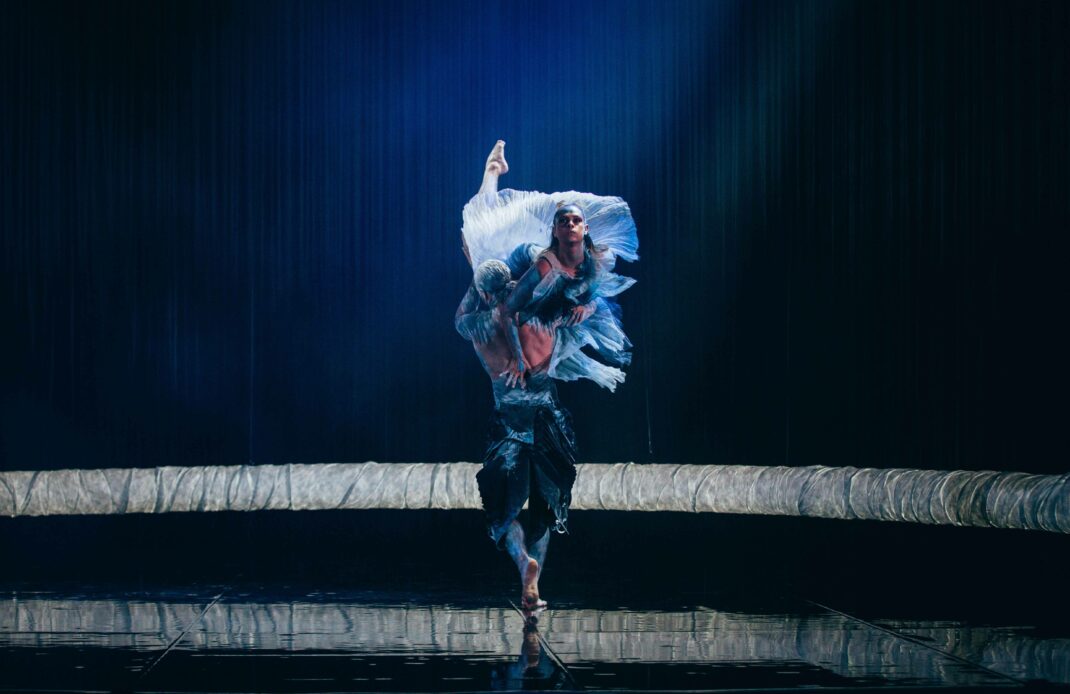

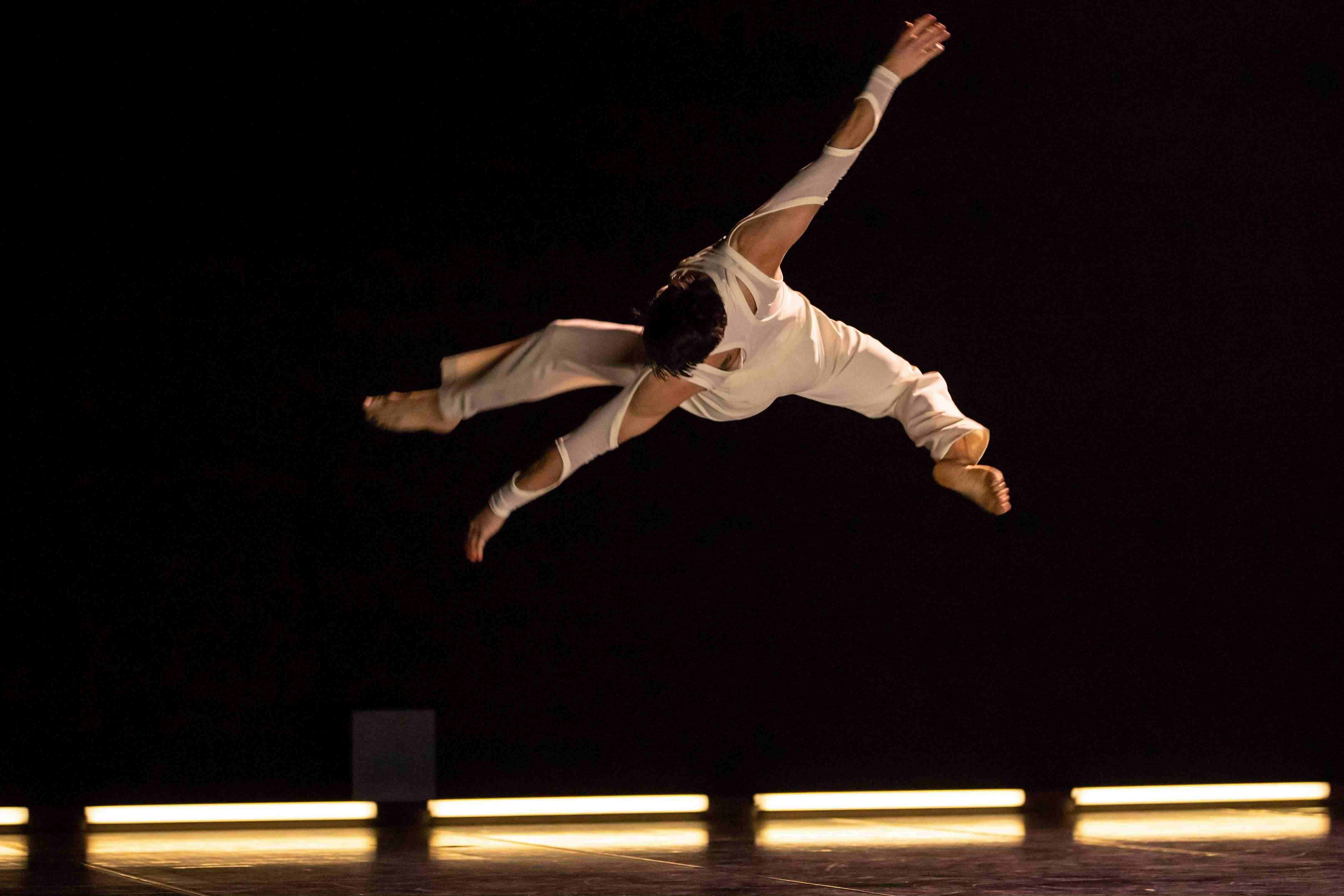

There was a lot to admire about Unhinged, the latest production from The Training Ground, a Canberra-based group designed to give advanced contemporary dance students from the region the opportunity to prepare for tertiary and/or pre-professional dance courses. Most obviously, the dancers were absolutely brilliant when dancing together. Great coaching of course but how stunning it was to watch the beautiful manner in which they danced as one when unison was required. Not only that, their hair and make-up were impeccable and gave them such a professional look, and one that fitted well with the characters they represented (dolls in most cases).

The second outstanding production feature was the film that so often took on the role of a background set. Created by Trent Houssenloge and Chris Curran of Cowboy Hat Films, the film component was at times a fluid, abstract image, but at other times it was a 3D creation that seemed to set the dancing in a space beyond the stage. At times the setting was an outdoor venue, at others an inside view of an artist’s studio or factory. A wonderful addition to the production.

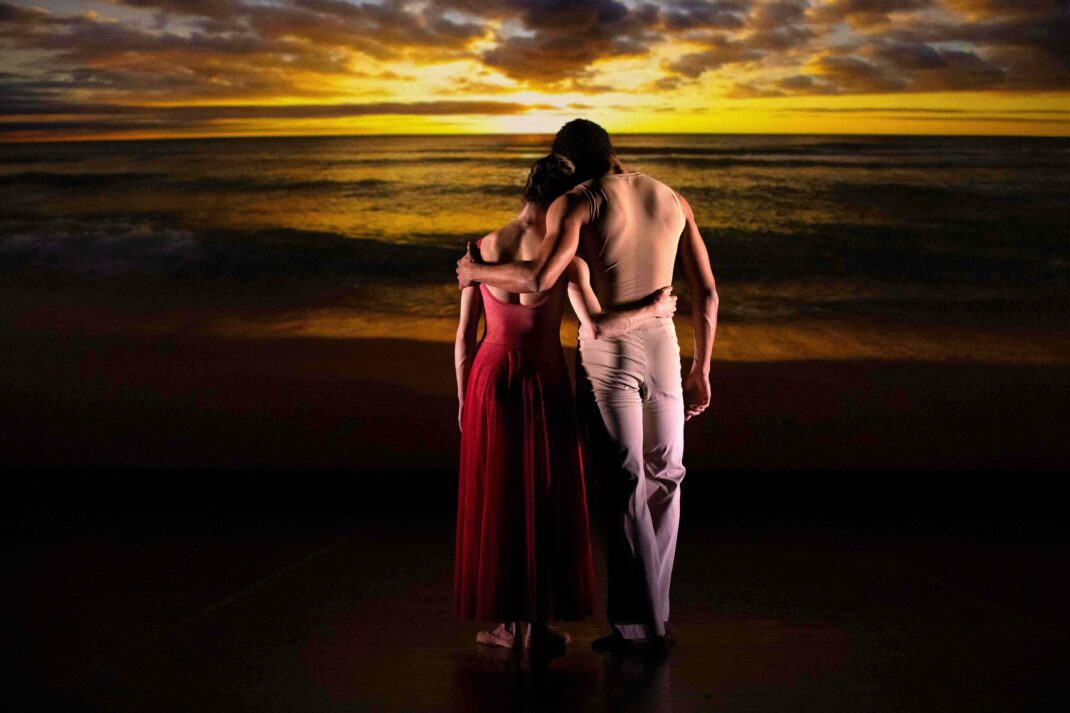

Unhinged was inspired by the well-known ballet Coppélia but, as is the way of Bonnie Neate and Suzi Piani who direct The Training Ground, the familiar story was given a new slant. The main characters, Swanhilda (Alice Collins); Franz (Joshua Walsh); Coppélia, a doll who is brought to life (Larina Bagic); and Dr Coppélius, a doll maker (Imogen Addison); remained in the new story, which centred on the fact that Swanhilda was enraged by Franz’s attention to Coppélia. Swanhilda was, apparently, the ‘unhinged’ character. The relationships between the characters developed and changed over the course of the production and the whole ended in a somewhat surprising manner with a destructive fire, although the work continued for several minutes after that.

Unfortunately, I have to say that for me the story did not unfold as strongly as was needed for the rage of Swanhilda (usually Swanilda—no ‘h’ in the spelling of the name in the traditional ballet) to be really noticeable. Nor was it really clear who Franz was in the town in which he lived. In fact, none of the main characters held the stage, that is acted, in a way that gave any real strength to their characters, despite the unison dancing and the make-up and hair styles. So, it was just as well that the work had a powerful visual element to enjoy.

The Training Ground is an excellent initiative, especially given that there is an aim there to keep dancers in Canberra if possible rather than have them go elsewhere to pursue a career. But I wonder if it would not be more advisable to make brand new works rather than aim to give a different slant on a well-known ballet? Romeo and Juliet worked well as the 2022 production but Coppélia is a different ballet, not as widely known as R & J, not so emotionally human perhaps, and maybe therefore one that does not lend itself so well to new slants? Perhaps a dramaturg would have been a useful addition to the production?

Michelle Potter, 30 July 2023

Photos: © ES Fotografi