4 June 2021. Lyric Theatre, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

I last saw Greg Horsman’s production of The Sleeping Beauty for Queensland Ballet (originally made for Royal New Zealand Ballet) back in 2015. Then I made a flying, unanticipated trip to Brisbane because I needed to see a different version from the one created by David McAllister for the Australian Ballet. I disliked the McAllister production, which was not about Aurora to my eyes, and in which everything was overpowered by the design elements. I came away from that initial Brisbane experience much more satisfied that Aurora had a role in the ballet, and that the collaborative elements worked with each other to create a whole without one element dominating all.

Having all that out of my system, this time I was able to concentrate on other aspects of the production. Horsman has reimagined certain parts of the storyline and, while this is now a relatively commonplace procedure, it has to be done really well and with a sound reason for changing things. The main issue for me was making Carabosse too much like the other fairies. She wore the same style tutu as the others (except it was black and had transparent sleeves). But sometimes she danced together with the other fairies and somehow, despite representing the spirit of evil, she seemed to recede into the background as a major player in the narrative. The role was performed quite nicely, technically speaking, by Georgia Swan but I wanted a Carabosse who stood apart, strongly, from the others. It just didn’t happen.

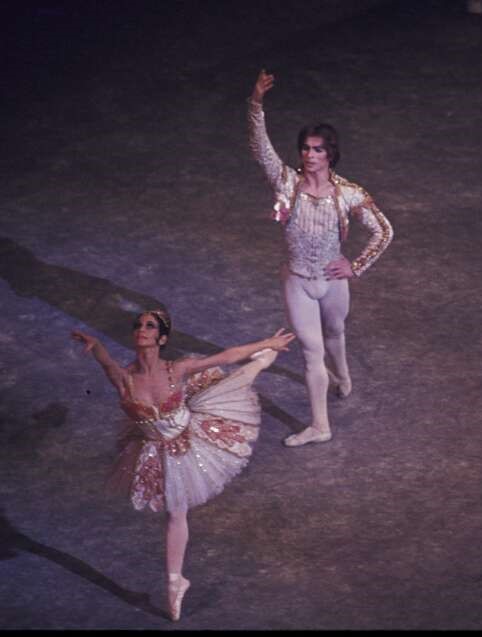

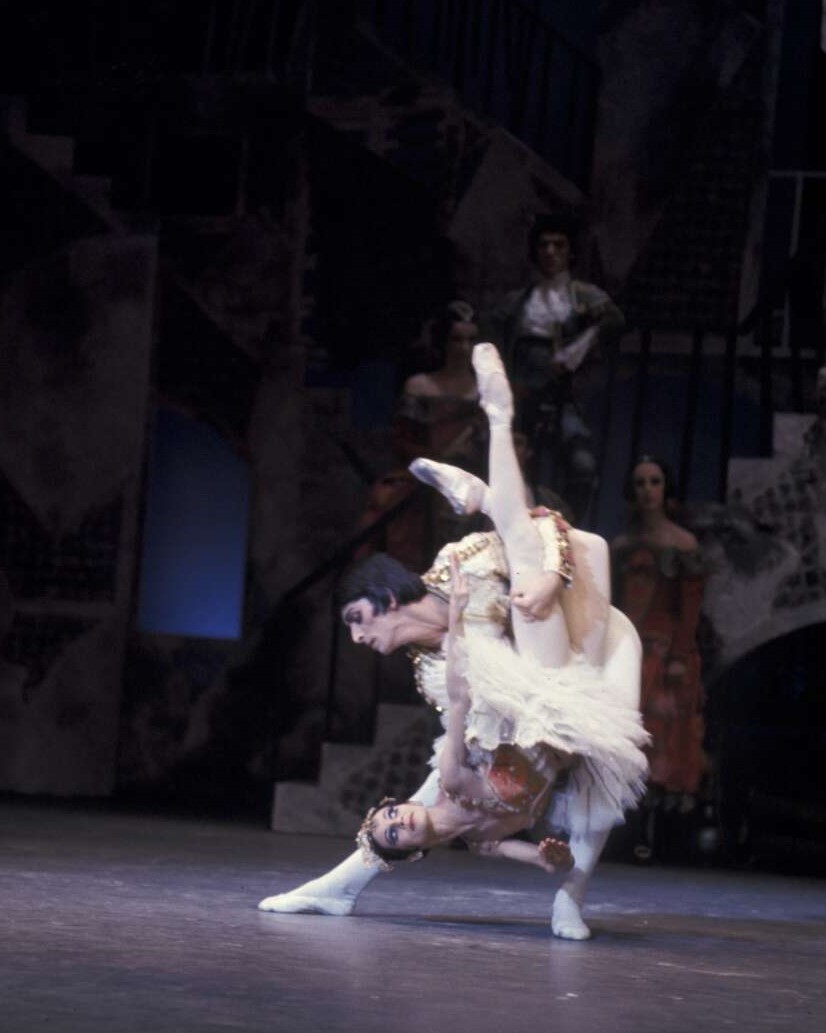

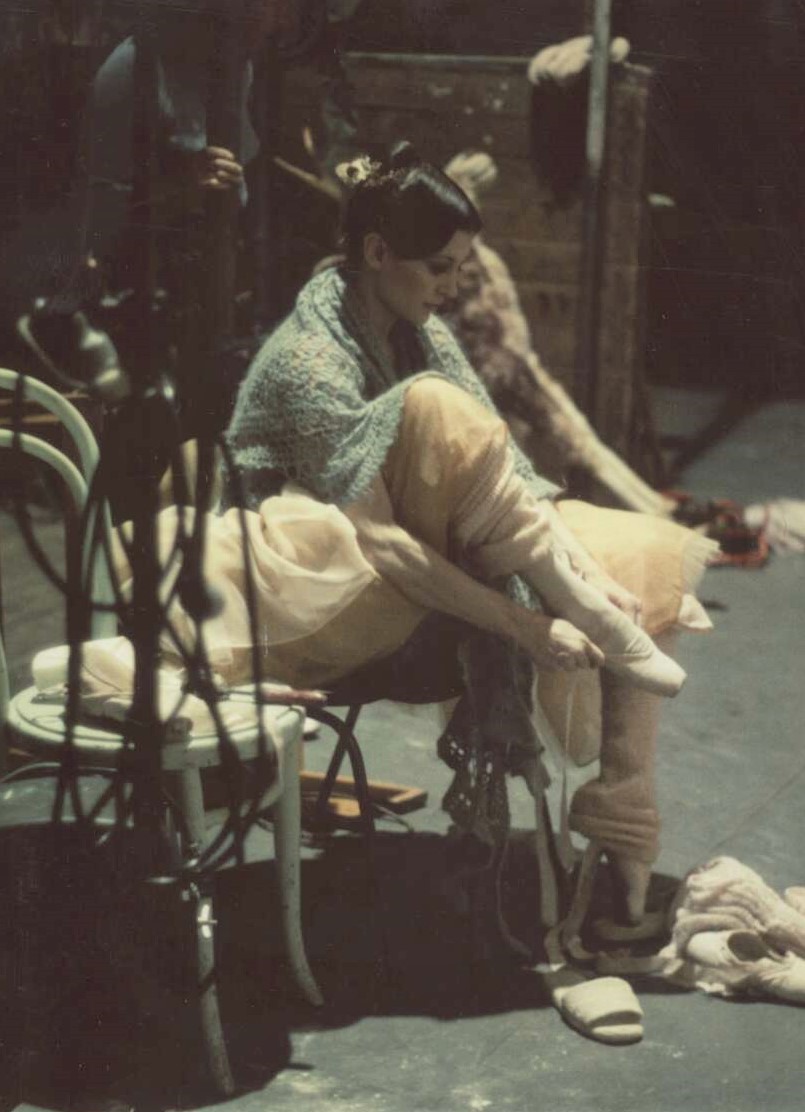

The leading roles of Aurora and the Prince were danced by Neneka Yoshida and Victor Estévez. Yoshida danced pretty much faultlessly but didn’t seem to be as involved in her role as I have seen from her on previous occasions. On the other hand, Estévez was not only a strong performer in a technical sense (his entrance at the beginning of the second act—the Prince’s hunting party—was spectacular and drew applause), but he had the carriage and demeanour of a prince at every moment.

Lucy Green and Kohei Iwamato were the Bluebirds for this performance. While Green and Iwamoto performed beautifully in terms of technique—and all those beats, including the series of brisés volés, need strong techniques—I was disappointed (and I often am). The story behind the Bluebird section is that he is teaching her how to fly and that she is listening to him. This backstory rarely comes across and it didn’t on this opening night. It was a shame about Iwamato’s costume, too. It had a very high neckline that practically removed his neck from sight.

The highlight of the evening for me was the Prince’s hunting party scene. Estévez I have mentioned. His friends, danced by David Power and Joel Woellner, and Gallifron the Prince’s tutor, a role taken by Vito Bernasconi, brought light and shade, some amusement, and good dancing and acting to the scene.

Choreographically Horsman has kept much of what we think of as the original movements, especially in the various pas de deux and solos. But where he has made choreographic changes there is little excitement. Much is predictable. Lots of arabesques. Lots of retiré relevé type movements.

So, all in all I found the production and the performance somewhat disappointing. In fact I began to wonder about remakes of well-known classics. While there will always be changes of one sort or another to any ballet, it takes an exceptional choreographer to do a remake. Those who succeed usually bring a completely new work to the stage. Liam Scarlett did it with his Midsummer Night’s Dream. Graeme Murphy has done it on several occasions. I thought Horsman did it (almost) with his Bayadère, despite the fact that there were certain issues associated in some minds with current thoughts re political correctness.

But this Sleeping Beauty was not a remake, just the same story with a few elements added, a few removed, and some changes to the way the story unfolded. It made me long for someone to do something completely new, or to revive an old fashioned production! Seeing it in 2015 was just a relief after the McAllister production. In 2021 perhaps my reservations were a result of having watched the Royal Ballet’s recent streaming of its hugely engaging presentation of the Ninette de Valois Beauty of 1946?

Michelle Potter, 7 June 2021

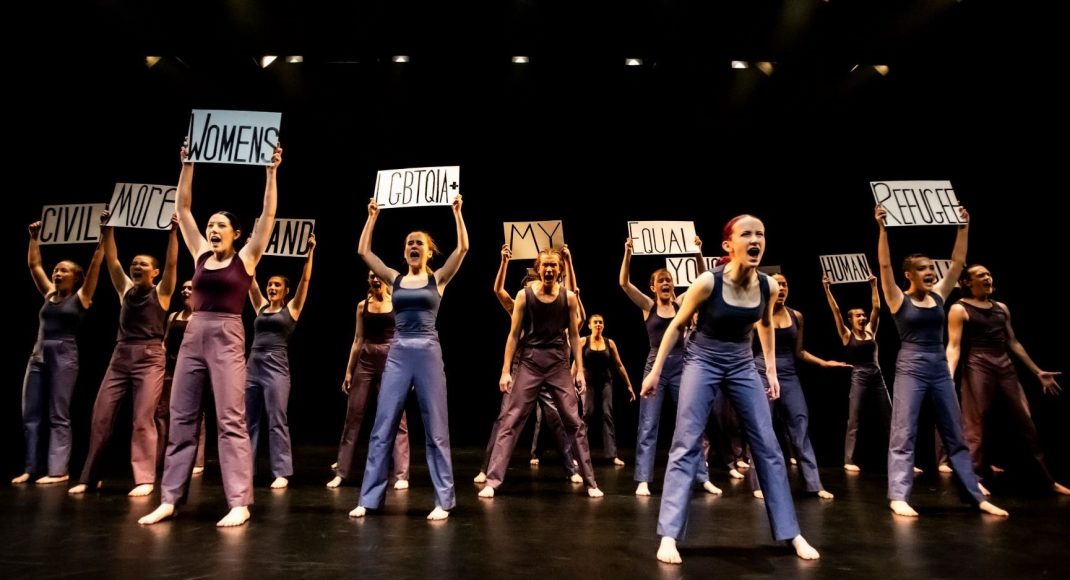

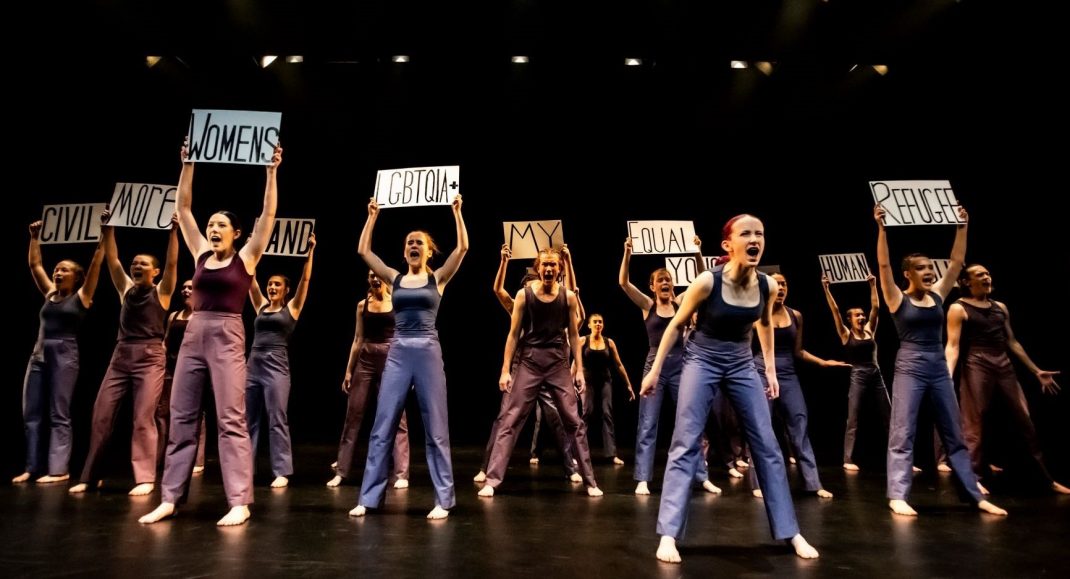

Featured image: Serena Green, Laura Tosar, Chiara Gonzalez and Mia Heathcote as the Fairies in The Sleeping Beauty. Queensland Ballet, 2021. Photo: © David Kelly