- Jennifer Shennan

I am thrilled to welcome Jennifer Shennan as a contributor to this website. Based in Wellington, New Zealand, Jennifer is a renowned dance writer whose major publications include A Time to Dance: the Royal New Zealand Ballet at 50 (Wellington: RNZB, 2003) and The Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60 (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2013), which she edited with Anne Rowse. Jennifer teaches dance history and anthropology and has a particular research interest in the Pacific. Her own teachers were Poul Gnatt and Russell Kerr. Now that is a proud heritage!

Jennifer’s first contribution was her tribute to Harry Haythorne and I look forward to publishing more of her writing as 2015 proceeds.

- ‘Pulse: reflections on the body’

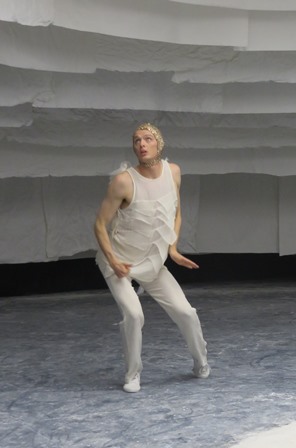

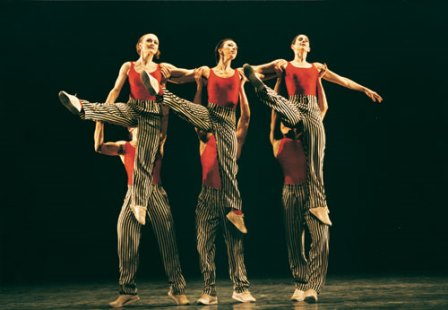

The Canberra Museum and Art Gallery has been running a show since October 2014 called ‘Pulse: reflections on the body’. The exhibition has on display items by a range of artists working across several media. Amongst a collection of works on paper and canvas and some sculpture, two dance items are included—Australian Dance Theatre’s 15 minute video of Garry Stewart’s Proximity, and James Batchelor’s video, Ersatz. Batchelor has also been giving some live performances during the run of the show. As seen in the image below, his performance takes place on the highly polished floor in front of his video installation and, as with all his work that I have seen, it is meticulous in its fine detail and in its interest in the stillness that surrounds movement.

(The hand-blown glass objects in the foreground of the image are from a work by Nell)

- Arthur Murch and the Ballets Russes

I was pleased to be contacted during January by the daughter of Australian artist Arthur Murch, who told me that her father had travelled to Australia from Italy on board the Romolo with some of the dancers coming to Australia for the 1939–1940 Ballets Russes tour. I was curious because I had been under the impression that the dancers had come from London on board the Orcades, with another group arriving from the West Coast of the United States on board the Mariposa. The two groups met in Sydney and gave their opening performance at the Theatre Royal on 30 December 1939.

It seems, however, that there were a few Ballets Russes personnel who did indeed travel on the Romolo from Genoa. They included Olga Philipoff, daughter of Alexander Philipoff, de Basil’s executive assistant; Marie (Maria) Philipoff, mother of Olga; and dancer Nicolas Ivangine. The Romolo was the last boat to leave Italy before Italy joined the war and Murch was returning to Australia after spending time in various parts of Europe. The Romolo and its passengers have, it seems, escaped the attention of Australian Ballets Russes scholars so far, as has Murch’s connections with the company. To date I have seen a photograph of a beautiful head sculpture Murch made of Mme Philipoff, and a photo of Olga Philipoff and Ivangine on the deck of the ship. I look forward to reporting further on this discovery at a later date.

- Dance and criticism

The newest issue of Dance Australia (February/March 2015) includes its annual survey by critics from across Australia, although this year editor Karen van Ulzen has expanded the space given to the survey so that critics are able to give fuller accounts of their choices. It makes the survey more than simply a list and gives a touch of analysis, an essential element in good dance writing. The new look is a welcome initiative that I hope continues. It is always interesting, too, to see how varied the choices are.

- Press for January 2015 (Update May 2019: Online links to articles published prior to mid 2015 in The Canberra Times are no longer available).

‘Vibrant, expressive show.’ Review Dancing for the gods, Chitrasena Dance Company, The Canberra Times, 19 January 2015, ARTS p. 6.

‘In the WRIGHT frame of mind.’ Profile of Sam Young-Wright of Sydney Dance Company, The Canberra Times, ‘Panorama’, 24 January 2015, pp. 10–11.

‘A classic in its own right.’ Preview of Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake, The Canberra Times. ‘Panorama’, 31 January 2015, p. 18.

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2015