12 May 2018, Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

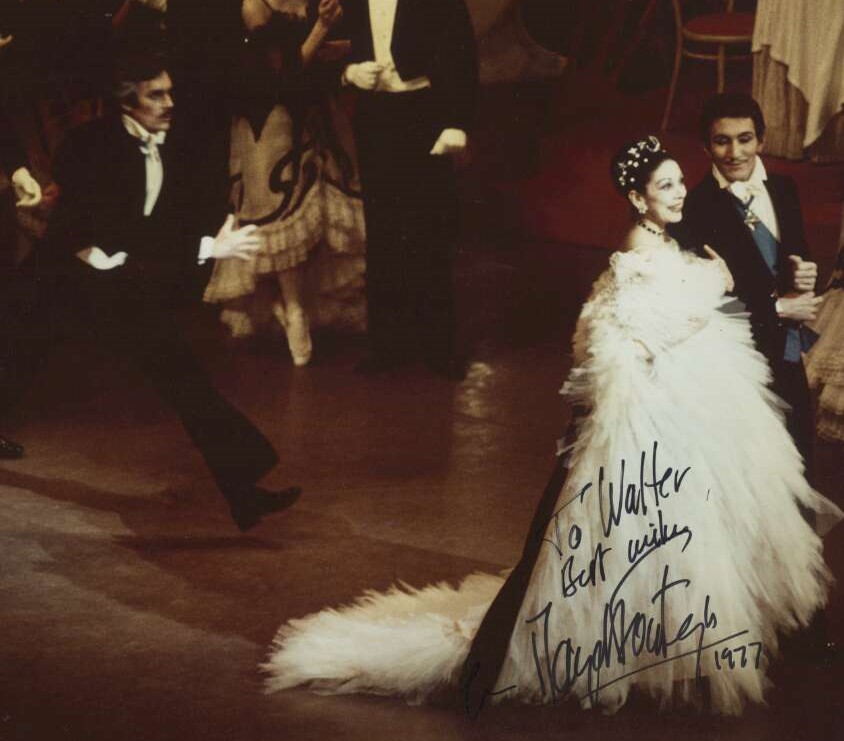

If you enjoy sitting in the theatre and being swept away by waltzes and ladies being lifted high in the air by their male partners, along with elaborately decorated costumes and sets and nothing too challenging in the way of storyline, then the Australian Ballet’s Merry Widow is for you. This production was last seen in 2011 but dates back to 1975 when it was commissioned by Robert Helpmann as the first full-length ballet to be made on the Australian Ballet. Choreographed by Ronald Hynd, designed by Desmond Heeley, with music by Franz Lehar arranged by John Lanchbery, and a scenario by Helpmann, it was in the early days closely associated with Margot Fonteyn. She performed the role of the Widow, Hanna Glawari, in Australia as well as elsewhere during guest seasons with the Australian Ballet.

But Australian Ballet principals of the day, including Marilyn Rowe, Marilyn Jones, Lucette Aldous, John Meehan and Kelvin Coe, and others throughout the years, also made it their own. Rowe was repetiteur for this 2018 production.

In the cast I saw Amy Harris and Brett Simon danced the leading roles of Hanna Glawari and Count Danilo Danilowitsch, former childhood sweethearts whose attraction to each other is eventually renewed. While they both danced strongly, for me their involvement in the unfolding story was not the highlight of the show. On the other hand, I admired Sharni Spencer and Joe Chapman as the secondary leads of Valencienne and Camille, the Count of Rosillon. They invested more into the realisation of their characters and, as a result, were much more captivating to watch. And their pas deux in Act II, was really the choreographic highlight amongst all the waltzes and other predictable steps.

There was some strong character work from the male corps de ballet of Pontevedrian dancers in Act II and my attention was especially drawn to a gentleman, who I think was Joseph Romancewicz. He not only danced well but maintained his character when not dancing. It doesn’t always happen and when it does it is very noticeable.

Audiences love this ballet and it is clearly a money-spinner for the Australian Ballet, but after more than forty years I think it needs a redesign. Heeley’s costumes are individually glamorous and suitably of the Belle Epoque period, if sometimes rather too strongly coloured. But when seen en masse against his over lavish sets, and when lit with strong theatrical lighting, the overall design is unsubtle and inelegant to the point of seeming tasteless.

Michelle Potter, 13 May 2018

Featured image: Dancers of the Australian Ballet as Can Can ladies in The Merry Widow, Act III, 2018. Photo: © Daniel Boud