14 December 2019, Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

My thoughts on David Hallberg’s guest appearance with the Australian Ballet in Alexei Ratmansky’s Cinderella were posted on DanceTabs on 16 December 2013. Below is the text. The DanceTabs link is still available and includes 11 comments that were made on the story by readers.

The DanceTabs text (without comments) is reposted below.

When David Hallberg was a child his inspiration to dance initially came from Fred Astaire whose old Hollywood movies Hallberg loved to watch. He admits he was obsessed. In those days he didn’t own a pair of tap shoes so, when Halloween was approaching, he attached coins to his shoes and tapped as a trick or treat act. Hallberg went on to take formal tap and jazz classes but it was not long before ballet drew him into a new dance world. His ballet teacher in Phoenix, Arizona, was Kee Juan Han, who recognised his talent but told him that it needed to be shaped. He was thirteen. There were no other boys in his ballet class but he persisted, nurtured by Han, and now, with his beautifully proportioned body, extraordinary feet, and easy, fluid technique he is the epitome of the danseur noble.

Hallberg has been in Sydney, Australia, guesting with the Australian Ballet as the Prince in Alexei Ratmanky’s new take on Cinderella, a production that was reviewed earlier in 2013 in DanceTabs. In this Cinderella the Prince makes his appearance early on in Act II, the ball scene. There is a huge build up to his entrance. The Prince’s four friends, who are in fact his minders, attempt to clear centre stage of guests; those guests engage excitedly with each other; and the Stepmother and her two daughters, Skinny and Dumpy, try to push themselves forward. The Prince arrives dressed in an elegant white suit with a tuxedo-style jacket worn over a smart vest. His entrance begins with a spectacular diagonal of grands jetés, and Hallberg’s entrance drew gasps and shouts of ‘bravo’ from the audience. His magnificently stretched jetés soared through the air, seemingly without effort. The perfectly placed grands pirouettes that followed whipped around in spectacular fashion, and the entrechats sprinkled throughout his solo were quite the most perfect examples of that step that I have seen.

Hallberg played the role of the Prince in a very royal manner. He was slightly imperious as he gave orders to his entourage and, while he greeted his guests at the ball in a charming manner, he was regally distant. Similarly, although when he first saw Cinderella, danced by Australian Ballet principal Amber Scott, he was instantly attracted to her, there was still something withdrawn about his reaction to her. There were moments when he seemed to me to be more like the Prince in a traditional Swan Lake Act I rather than a character in a twenty-first century reimagining of an old story.

Hallberg is no stranger to Ratmansky’s work. He has appeared in at least five others of his works and next year he will dance in Lost Illusions with the Bolshoi Ballet. Of working with Ratmansky, Hallberg says: ‘He is so clever. I love the nuances in his work. He has his signatures but he is so relevant, so of his era’. So Hallberg’s choice to play the Prince in a manner that was at odds with how the rest of the cast handled Ratmansky’s creation is a curious one. It is especially so because Hallberg says that when he is not in the theatre he loves to see other art and that his particular taste is for the contemporary. Hallberg’s dancing was, of course, stunning to watch. I especially admired his dancing in the scene where he travels the world looking for the owner of the glitzy shoe. Much of Ratmansky’s choreography for this section is full of lightning-fast moves that often change direction quickly and Hallberg threw himself into it with gusto. And his several pas de deux with Scott had an incredible lyricism. But to do full justice to Ratmansky’s reimagining of the story, this Cinderella needs a less classical reading than the one Hallberg gave us.

As a result the evening fell a little flat, especially as Scott’s portrayal of Cinderella lacked the sparkle and individualism that marked performances by Leanne Stojmenov, on whom the role was created. There were some stellar performances from others in the cast, especially Amy Harris as the Stepmother who let fly with her tantrums when her hairdresser failed to live up to her expectations, or when the shoe didn’t fit. But the work does need the Prince to be a strong, contemporary character. Despite the fact that he is royalty, his behaviour has to fit the contemporary mood of the ballet.

In many respects it is a shame that Sydney was chosen as the city to host Hallberg, despite the fact that Sydney clearly offers great photo opportunities. The inadequacies of the stage of the Joan Sutherland Theatre in the Sydney Opera House are well known. The stage is small and is short on wing space, and that’s even before we get to the orchestra pit, which is partly underneath the stage and is the bane of musical directors and orchestral players. Ratmansky’s Cinderella looked cramped in Sydney compared with the magical and mesmerising effect it had on the bigger Melbourne stage. However, it perhaps would not have made a difference had Hallberg danced in Melbourne. Space was not the major issue.

Hallberg gave his last show in Sydney on 14 December and then flew out to Paris to make his debut with the Paris Opera Ballet. I thought he missed the point of Ratmansky’s take on Cinderella. But it will take me a long while to get over those astonishing entrechats.

Michelle Potter, 16 December 2013

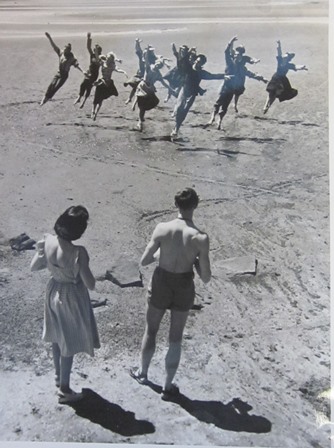

Featured image: David Hallberg in costume for the Prince in Alexei Ratmansky’s Cinderella. The Australian Ballet, 2013. Photo: © Wendell Teodoro