Ros Warby’s Monumental has been around since 2006 but I had not seen it for one reason or another. So it was more than irritating to arrive at its showing during Spring Dance to be told that there was no program sheet. ‘Oh, it’s the last performance’, I was told. Well this is the digital age when it doesn’t take long to print off a few more copies. And there were only two performances and I was at the second, so it seems slack that such a small number of shows could not be catered for in the first place. Besides, it is offensive to the artists involved when the audience doesn’t have the opportunity of reading who did the lighting, who made the costumes, who composed the music and so forth.

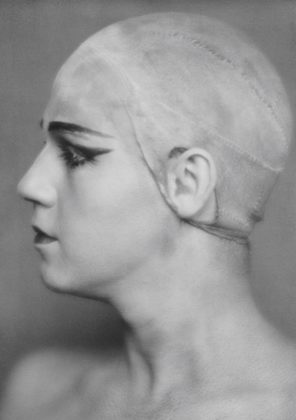

But to the show! Monumental, a solo work, focused on two generic figures—a swan and a soldier. I’m not sure they had any relationship to each other but certainly as each took the stage we were reminded of the fragility and perhaps the futility of the human condition and experience. The swan, which may or may not have been Odette from Swan Lake or the dying swan of Anna Pavlova fame, twitched and fluttered nervously. Warby’s headdress of a white skull cap/swimming gear looked incongruous with her white tutu but went well with her bare feet. Then the swan began to share the stage with footage of birds and of Warby herself. A beautiful blend of the living and the mechanical began to emerge and more resonances began to surface in one’s mind.

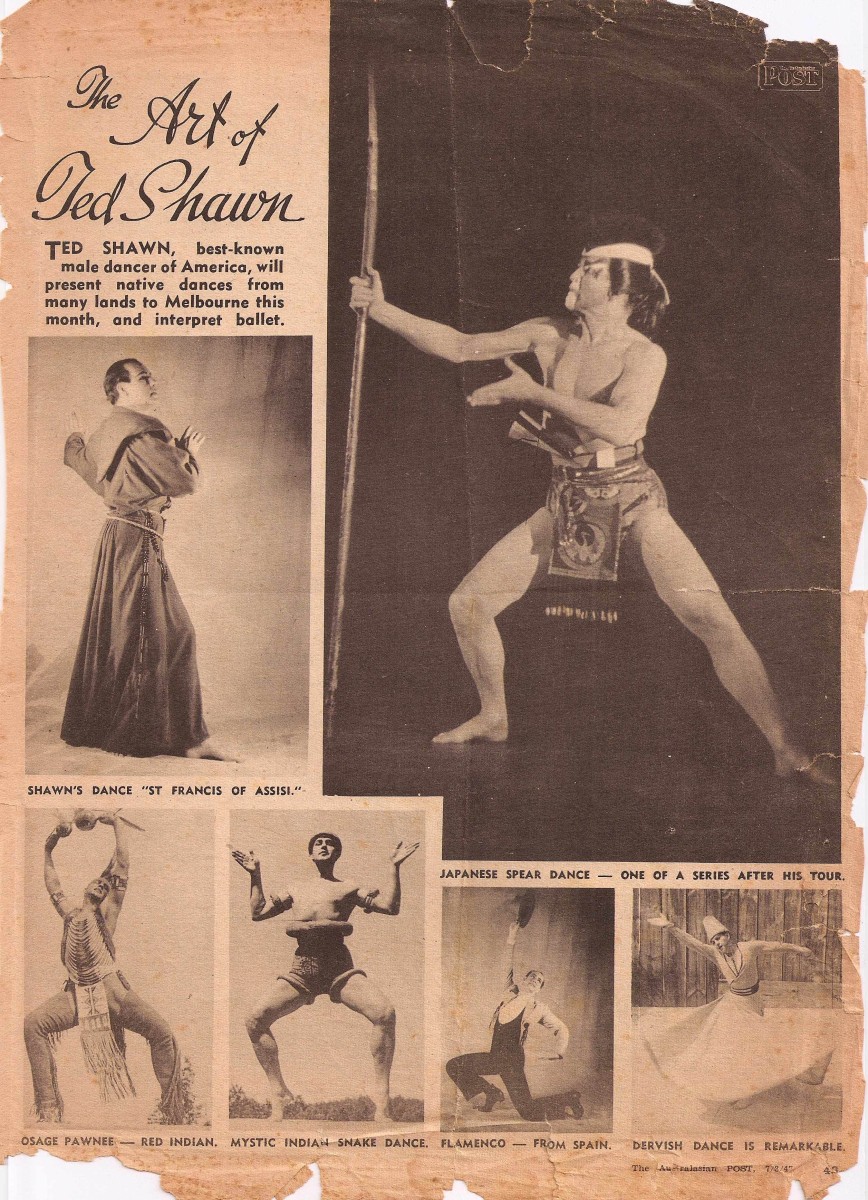

The soldier, dressed in a black jumpsuit and a headdress that recalled that worn by the Siren in the Ballets Russes production of The Prodigal Son, was a little less successful, although Warby demonstrated her versatility as a dancer, changing from the twitching anxiety of the swan to a precise, neat way of covering space—dare I say a militaristic way of moving? The Lone Ranger allusion (‘Hi, yo silver. Away’) as the soldier became a horse was again a complex layering of meaning especially as the footage changed from marching feet in a harsh environment to balletic feet, and as the soldier/horse became a black swan.

Warby’s Monumental is a strong work but not easily ‘understood’. It is emotional to a certain extent and juxtaposes ideas as non sequiturs. So it fits in a way with the Spring Dance focus on the expressionist legacy of Pina Bausch. But Warby has quite a cerebral, even dry approach to her creative practice that seems to me to be the antithesis of the Bauschian approach. Nevertheless, Monumental is a work worth watching and pondering over.

However, I do wish that Warby would avoid including obvious balletic language as part of her choreography. No matter how much one’s early ballet training may be ‘imprinted’ on the body (it’s on mine too!) one reaches a stage where turning pirouettes in a circle no longer looks the way it should. Without daily and intensive ballet classes and ongoing use of the ballet technique in a professional way, no dancer can do justice to the intrinsic qualities of the balletic vocabulary. The body seems like a slightly out of tune musical instrument, the steps suffer and we are faced with an unintended (I think) denigration of the vocabulary.

After the show I was able to confirm that the footage and lighting were the work of Margie Medlin and the cello score was by Helen Mountfort. Medlin and Mountfort are Warby’s regular collaborators but not everyone in the audience would have known that without a program sheet.

Michelle Potter, 10 September 2011