Olga Spessivtseva, graduate of the St Petersburg Theatre School, famed interpreter of Giselle, star of Serge Diaghilev’s ill-fated 1921 London production of The Sleeping Princess, and legendary ballerina of the Paris Opera in the 1920s, was contracted to come to Australia in 1934 as principal dancer with the Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet. Spessivtseva, or Spessiva as she was officially known on the tour, joined the company in Singapore, along with her companion (the retired American businessman Leonard G. Braun), her dancing partner Anatole Vilzak, and others who were to join the company. Following the Singapore season, in which she did not perform, she travelled with the company through Java, where she did dance, and on to Australia where the company was to fulfil engagements in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and eventually Perth.

The Australian component of the tour has generated a good deal of interest as a result of the fact that Spessivtseva left the tour in an apparent state of mental distress following the Sydney season, which ran from 27 October to 28 November 1934. Exactly what happened to Spessivtseva is unclear and although her performances were, on most occasions, reviewed more than favourably by the press, most other accounts present a story of wildly eccentric and delusional offstage behaviour on her part. Anton Dolin, for example, in his biography of Spessivtseva, The Sleeping Ballerina, records that she complained she was being spied upon and that she was in terrible danger from unknown forces, that on one occasion she was found wandering on a deserted highway miles from town and so on.

The official story as given to Australian newspapers was that Spessivtseva sprained her ankle. Melbourne’s Argus newspaper reported on 1 December 1934, the day the Melbourne season was to begin:

‘A week before the end of the Sydney season the company suffered a severe loss when the first ballerina, Olga Spessiva, sprained her ankle. Mme Spessiva is resting in Sydney and may not be able to appear again for several weeks.’

However, Harcourt Algeranoff, who also danced with the company on this tour and whose letters to his mother provide a wealth of information about the company, has a slightly different version of events. Writing from Melbourne on 2 December 1934 his inside information is that Spessivtseva had already left for Europe:

We’ve had rather a blow as Spessiva is ill and although it is no known publicly, she’s sailed for Europe. She has promised to rejoin us some months hence when she is better.’

Dolin, however, gives a quite different account of Spessivtseva’s movements. He maintains that Spessivtseva was sent to recuperate in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney for some weeks after her last performance in Sydney. Although no evidence for the Blue Mountains story, other than Dolin’s account, has yet come to light it does have a certain plausible aspect to it. In his unpublished work ‘For Olga Spessivtzeva. A memoir of loving’ Dale Fern suggests that what has not been fully recognised is that Spessivtseva was physically frail during her dancing career. He writes:

‘What was consistently overlooked, by managers and dancers alike, in 1916 [her appearances with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in the United States], in 1921 [her performances in Diaghilev’s Sleeping Princess], and in 1934 [her tour with the Dandré-Levitoff company], was Olga’s frail constitution, her delicate physical condition. She was not well. Tuberculosis visited her regularly.’

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the crisp mountain air found in the Blue Mountains was promoted to Sydneysiders as a kind of health tonic for many ailments including, according to Blue Mountains Park historical information, tuberculosis, asthma, bronchitis, malaria, stress, anaemia, and heart troubles. In the early part of the twentieth century, the small town of Wentworth Falls in the heart of the Blue Mountains was the site of two very well known institutions — the Queen Victoria Home and Bodington Sanatorium — both of which cared for patients with tuberculosis. In addition, the Hydro-Majestic Hotel, located higher into the mountains at the village of Medlow Bath, was built by Mark Foy of the wealthy Australian retail family as a ‘hydropathic sanatorium’. Unlike the Wentworth Falls institutions, where conditions appear to have been spartan and somewhat unpleasant according to the patients who have reported on life there, the Hydro-Majestic and its surrounds were a prestigious and socially desirable health retreat and its guests often included those prominent in the arts. The kinds of treatments available were listed in one promotional booklet. They included electric water and massage, electric light bath, vibration massage, general vibration massage, local hot air, local general massage, and various medicated baths.

It is conceivable that Spessivtseva, if indeed she did go to the Blue Mountains, may have gone to the Hydro-Majestic. But if Algeranoff was correct, Spessivtseva had no time to recuperate in the Blue Mountains or anywhere else before boarding a ship. However, ships’ passenger lists from Sydney that include her name, or that of her companion Leonard G. Braun, that might confirm such a departure remain to be located.

With regard to the official account of a sprained ankle, it was more than likely simply a story concocted by company management to explain to Melbourne audiences the fact that Spessivtseva was not performing there as previously advertised. Her name appeared as star attraction in Melbourne advertisements up until 28 November. By 29 November all reference to stars had been removed and by 30 November it was Natasha Bojkovich whose name was being promoted in Melbourne.

Nevertheless, just exactly what happened remains a mystery at this point. Spessivtseva’s name continued to be listed in newspaper advertisements for the last Sydney shows but there is a curious absence of reviews of the last program in the Sydney season and the last mention of her name in a performance seems to have occurred in The Sydney Morning Herald on 19 November when her performance in Raymonda was thought to be ‘cold’. In a review of the new program that opened on 24 November, the weekly newspaper Truth reported:

‘Owing to a slight indisposition, Spessiva did not dance. Her place was taken by Natasha Bojkovich, second ballerina of the company … The management announced that Spessiva will appear as usual tomorrow.’

Whether she appeared at all during the last week is questionable. Edward Pask in his Enter the colonies, dancing writes that she danced on the last night of the Sydney season but he quotes as his source ‘an [unidentified] observer at that performance’. Dolin also maintains that she performed on the last evening in Sydney. But neither gives any sound documentary reference to support his claim and it has to be assumed that neither attended performances in that last week to see for himself since Dolin was not in Australia at the time and Pask had not been born. As a counter report to Pask’s and Dolin’s comments, Valerie Lawson notes in an article in Brolga in December 2000 an unidentified, undated press clipping in a privately-held scrapbook that states:

‘[Spessiva] strained her ankle during the third week of the Sydney season and was ordered a brief rest by her doctor. She struggled on bravely for a few performances but was obliged to retire from the cast during the final week of the season.’

This report does, however, sound a little like an elaboration of the explanatory story given to Melbourne audiences. But as 1935 began, a further reference to Spessivtseva appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald as part of a summary of the previous year’s theatrical highlights. It supports Algeranoff’s account that Spessivtseva returned to Europe and alludes to her ill health:

‘Spessiva, who had been billed as the leader of the company, danced at every performance at first; but made only brief appearances, and, as time passed it became apparent that she was ill at ease. Still she danced brilliantly in “Carnival” and dropped out of the cast only when she strained an ankle. Since then, it has been revealed that she was in ill-health during the whole of the Sydney season; and now she has had to return to Europe leaving Natasha Bojkovich as a highly-efficient substitute leader in Melbourne.’

The story of Spessivtseva in Australia continues to remain something of an unsolved mystery. Until further evidence emerges, her activities during and immediately after the Sydney season continue to raise questions.

© Michelle Potter, 25 August 2010

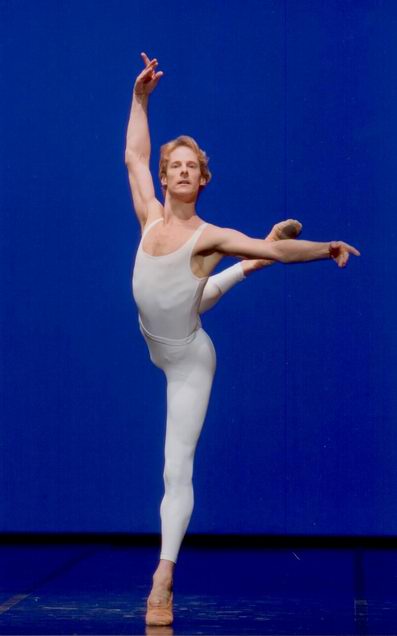

Featured image: Olga Spessivtseva at Central Station, Sydney, 1934. Photo: Sam Hood. Image in the public domain

Note: My substantial article on the Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet tour to South Africa, Singapore, Java, Australia, Ceylon, India and Egypt during 1934 and 1935 is currently being considered for publication by Dance Research (Edinburgh University Press).

Update 5 December 2013: The article mentioned above was published in Dance Research, 29:1, Summer 2011. See also the tag Olga Spessivtseva for further posts and ongoing comments.