29 July 2009, Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre

The dancers of Quantum Leap, the pick-up company of QL2 Centre for Youth Dance in Canberra, are not professional although their enthusiasm for dance is palpable. But the choreographers with whom these young dancers work each year for their annual project are professional. So any review of Quantum Leap is really a review of whether the choreographers have the understanding and expertise to harness raw energy and a varying range of skills to produce a coherent piece of work that maximises what these young dancers have to offer. This year the theme of the project was choice and, although the results were, as ever, uneven, some moments were remarkably successful.

Liz Lea’s contribution, Select Red, was for me the undoubted stand out section. Lea chose to work only with female dancers and drew on the stylised movements and poses that have featured in her works about extraordinary female dancers—such as Ruth St Denis—of the early twentieth-century. The dancers needed to move in unison and yet look individualistic and even idiosyncratic and they responded beautifully. Lea’s choreography had a calmness and velvety smoothness to it and again the dancers responded. Not all the dancers, however, had the maturity and sophistication to carry off the move from this first part of the piece to the second, which showed the individual choices they had gone on to make about dress (always red), movement and general lifestyle. Nevertheless, the point was made.

The second act featured some exceptionally energetic dancing choreographed by Marko Panzic and Reed Luplau, although it was not always clear which choreographer had contributed what. Perhaps the most exhilarating section was a vignette featuring twelve male dancers, performing with what can only be described as total passion, and dancing to assorted Latin rhythms. Again the choreographer had chosen well as far as dancers were concerned. The the loose-limbed, fast and furious dancing, which largely happened in nothing more than a line across the front of the stage, was vibrant and rousing.

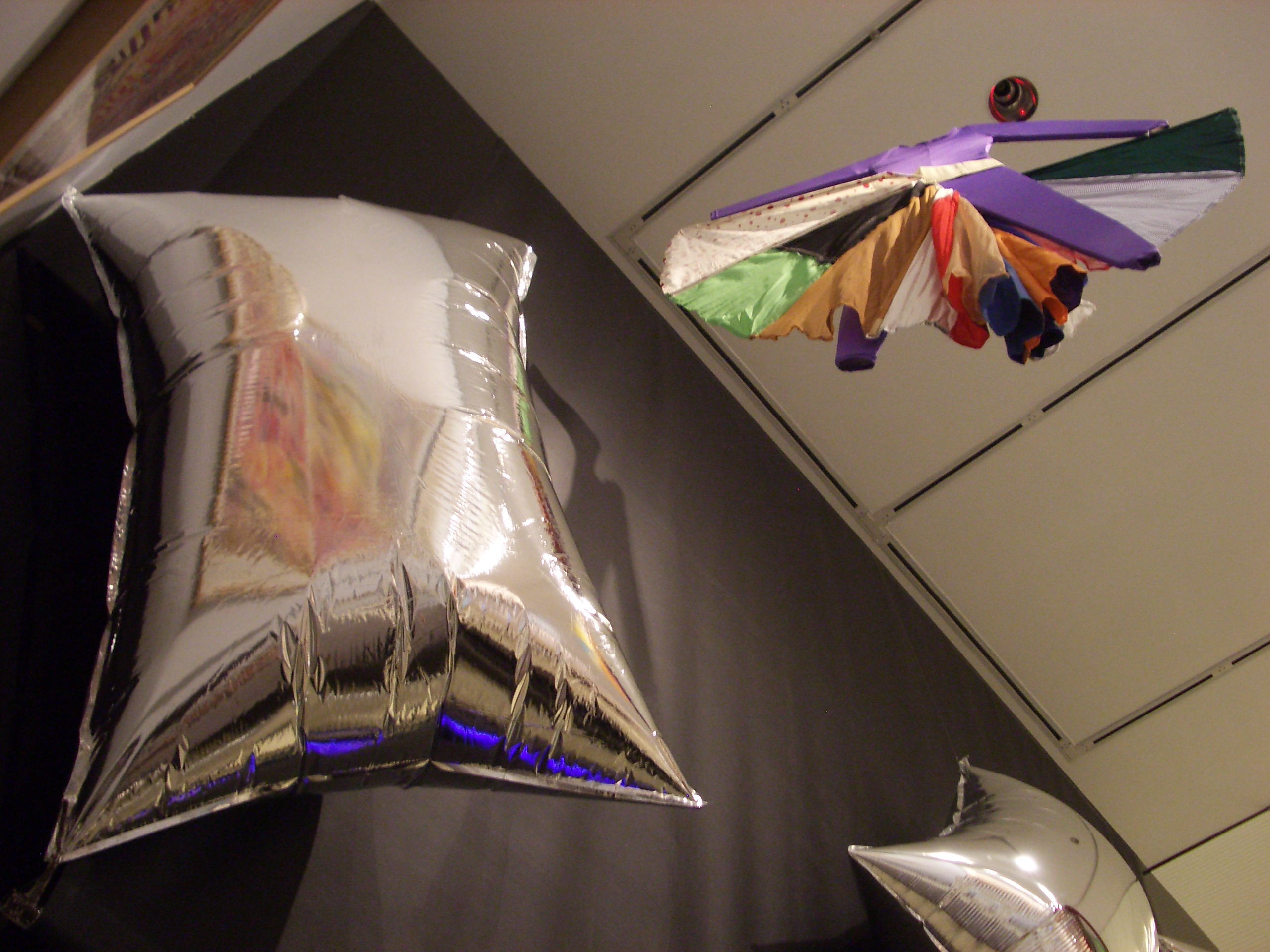

QL2 has a strong collaborative model at work with its annual shows. The two composers working with the company on this occasion, Nicholas Ng and Adam Ventoura, each produced an original score. Each was startlingly different from the other—a great experience for the dancers. Costumes were by Eline Martinsen and worked especially well in Select Red where small touches of red on the largely black outfits in the first section gave just a hint of what was to come later. Lighting designer Kaoru Alfonso also made an important contribution and again it was in Select Red that his designs were most effective. And for once the video footage that accompanied each piece was not intrusive but supported the works.

Michelle Potter, 2 August 2009

Featured image: Liz Lea’s Select Red. Photo: © Lorna Sim. Courtesy QL2 Centre for Youth Dance