- Russell Kerr Lecture 2024

The annual Russell Kerr Lecture for 2024 took place in Wellington on Sunday 25 February. The lecture honoured Sir Jon Trimmer, esteemed artist who made a huge contribution to ballet in New Zealand, and who died last year. I was to give a short talk in which I planned, by focusing on images including some costume designs, to show how Jonty, as he was familiarly known, was able to inhabit a role so magnificently. Unfortunately there was an issue with the plane that was taking me to Wellington from Sydney late on Saturday. The issue was not so much the plane itself but the weather in Wellington as we attempted to land. We were in fact diverted to Auckland (at around midnight) and a situation developed where we were told to wait in the transit lounge until the plane could take off to Wellington (the next morning). Well, without going into the highly unpleasant details, I ended up flying back to Sydney on the Sunday thus missing the lecture!

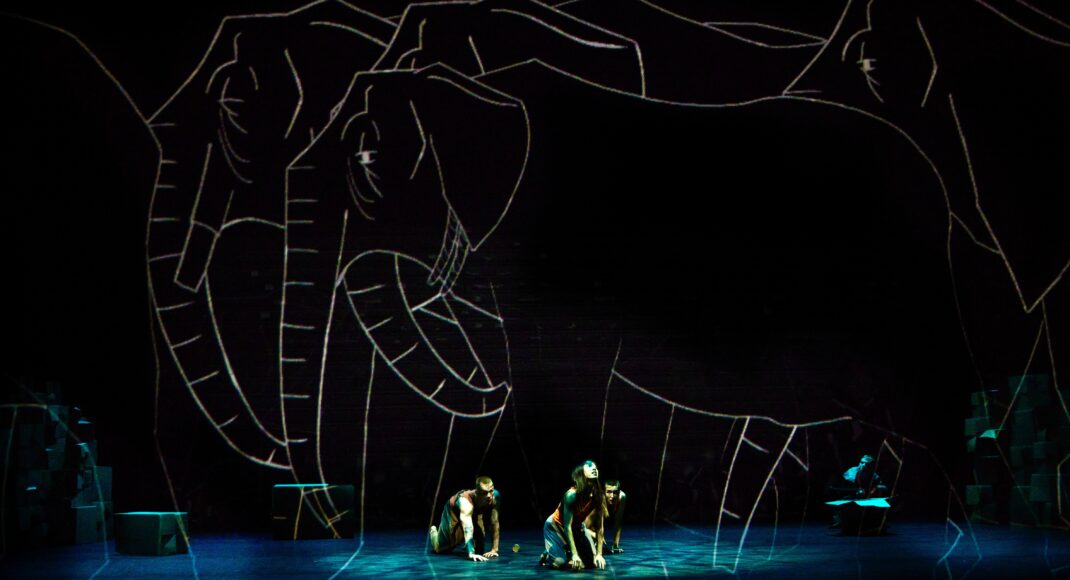

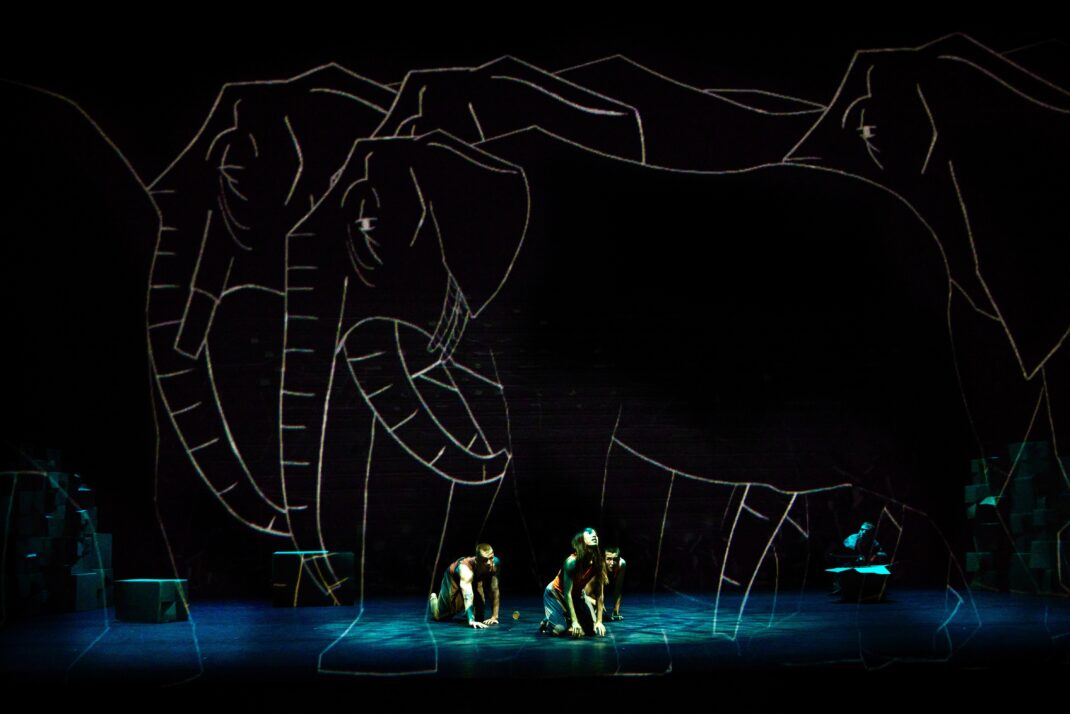

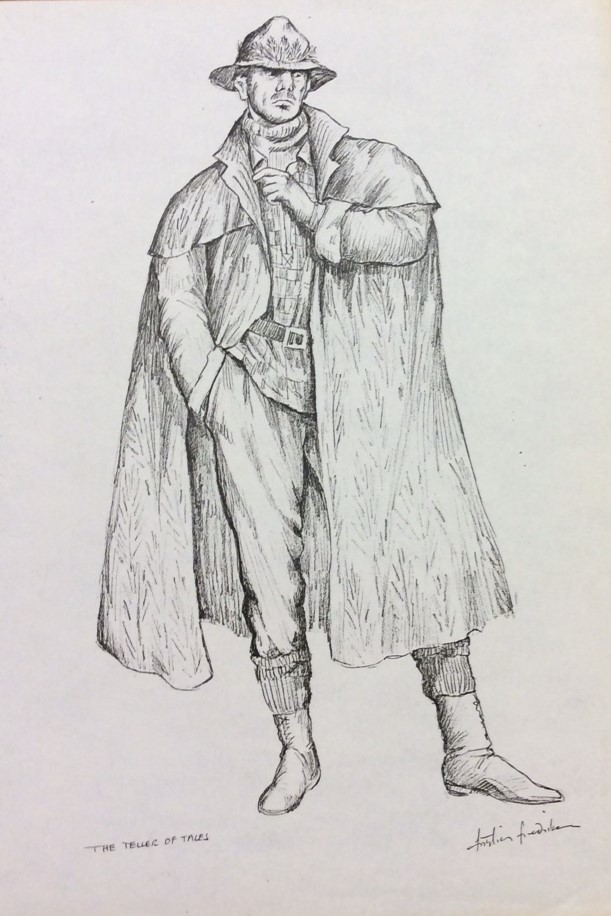

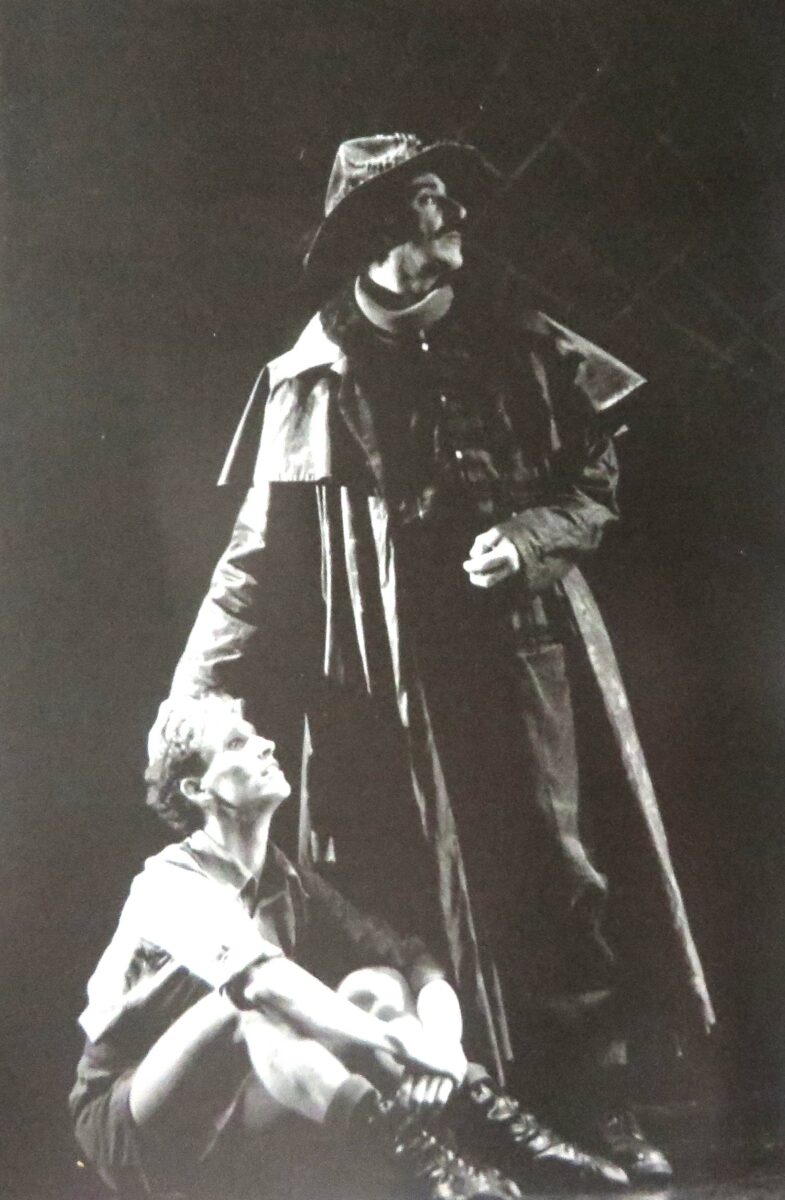

One of the most interesting parts of the proposed talk, at least for me, concerned a work called Tell Me a Tale choreographed by Gray Veredon in 1988 in which Jonty played the role of the Teller of Tales. In an interview I did with Jonty in 2018 he told me he was ‘a really “outback” character’ in the work. In a earlier interview (2012) with Royal New Zealand Ballet’s former wardrobe manager, Andrew Pfeiffer, I heard that ‘Jon was dressed in a Driza-Bone with a bit of silver fern wrapped through his hat and that emblem printed all over the top of his Driza-Bone.’ Below is Kristian Fredrikson’s design for the Teller of Tales alongside a photo of Jonty dressed in that outfit.

Andrew Pfeiffer also gave a very succinct outline of the story saying, ‘It was basically a storyteller telling a young boy the story of New Zealand in terms of the relationships between the Māori people and the colonists. Jonty was often just standing there with a young boy sitting at his feet. He was miming to the boy throughout the ballet with the ballet taking place on the side.’

And another aspect of that part of my talk was Veredon’s discussion of how the work came to be called Tell Me a Tale. Here is the audio link:

I was really disappointed not to have been able to give the talk and may work out later how to add the PPT to this site.

- Hannah O’Neill

It is always good to hear about Hannah O’Neill’s ongoing success with Paris Opera Ballet. Here is a link to the latest news.

- Lifeline Book Fair Canberra

The Lifeline Book Fair is a regular event in Canberra and has been for many years now. The most recent fair was in February 2024 and I ended up with seven dance-related items even though I had decided I have enough dance books for the rest of my life and wasn’t intending to buy anything this time. All in all the seven items cost me $27, which will go to helping Lifeline Canberra keep its crisis telephone service operating in the local area. I am currently reading the autobiographical I, Maya Plistetskaya, perhaps the most unusually written book I have ever come across. Next on the list is The Official Bolshoi Ballet Book of Swan Lake by Yuri Grigorovich and Alexander Demidov, whose chapters include ‘The Inside Story’, ‘Concerning One Delusion’, ‘A Painful Dilemma’ and other such fascinating titles. It promises to hold many matters that will be new to me I think.

Michelle Potter, 29 February 2024

Featured image: Jon Trimmer as Captain Hook in Russell Kerr’s Peter Pan. Royal New Zealand Ballet, 1999. Photo: © Maarten Holl