And we danced, a three part documentary from the ABC produced by WildBear Entertainment, looks at the first six decades of the Australian Ballet. The series makes use of archival footage held by the Australian Ballet, and that footage is complemented by photographs and interviews with former and current company staff and dancers, and with commentary from Ita Buttrose, current chairperson of the ABC.

I was originally going to wait until all three episodes had been screened before making comments. But the second episode, covering the two decades of the eighties and nineties, was so full of memorable moments that I decided I just had to comment on the second episode and mention some of those moments—the ones that especially moved me in some way.

It was always going to be hard to cover in 58 or so minutes everything of significance that occurred over two decades, especially when the two decades covered in the second episode were tumultuous in so many ways. There was the strike of the early 1980s and the various changes of artistic directorship that ensued; the AIDS epidemic; Paul Keating’s Creative Nation and the strong arts funding that developed under Keating; the era of Maina Gielgud and her eventual departure from the company; the arrival of Ross Stretton and his very different management style and artistic aesthetic; and more.

And we danced needed to be selective in what it covered in detail, but what I found especially engaging was the examination of how the company began to move from a pioneering company in its earlier years to one that was a mature arts organisation. While there were many ways in which an Australian identity began to emerge, and various social and cultural contexts were mentioned, particularly poignant were the comments by Stephen Page as he talked about Bangarra Dance Theatre and the Australian Ballet working together on Rites under the directorship of Ross Stretton.

Then, I couldn’t help but be impressed by the incredible range of choreography that those of us who were lucky enough to have been audience members at the time were able to experience. One of the most interesting sections concerned the last program curated by Maina Gielgud before she left the company. Her triple bill of Stanton Welch’s Red Earth, Meryl Tankard’s The Deep End, and Stephen Page’s Alchemy was so strongly Australian and the comments on why (or how) this program happened were well contextualised. And of course it was great to see footage of Stanton Welch’s Divergence, another exceptional work from the Gielgud period.

I also enjoyed the discussion of Spartacus. It has never been one of my favourite ballets, neither in the Laszlo Seregi (Australian Ballet premiere 1978) version nor the more recent one by Lucas Jervies. But looking at the brief footage shown of the Seregi production I was bowled over by Steven Heathcote in the main role. The drama he injected into every movement was just brilliant. And then there was the wonderful story of the poster with the sexy image of Heathcote that was consistently stolen when the production was taken to the US.

It was also interesting to see and hear comments from former dancers and directors, especially Marilyn Rowe and Marilyn Jones who played major roles in the 1980s. More of the full project later.

Michelle Potter, 26 July 2021

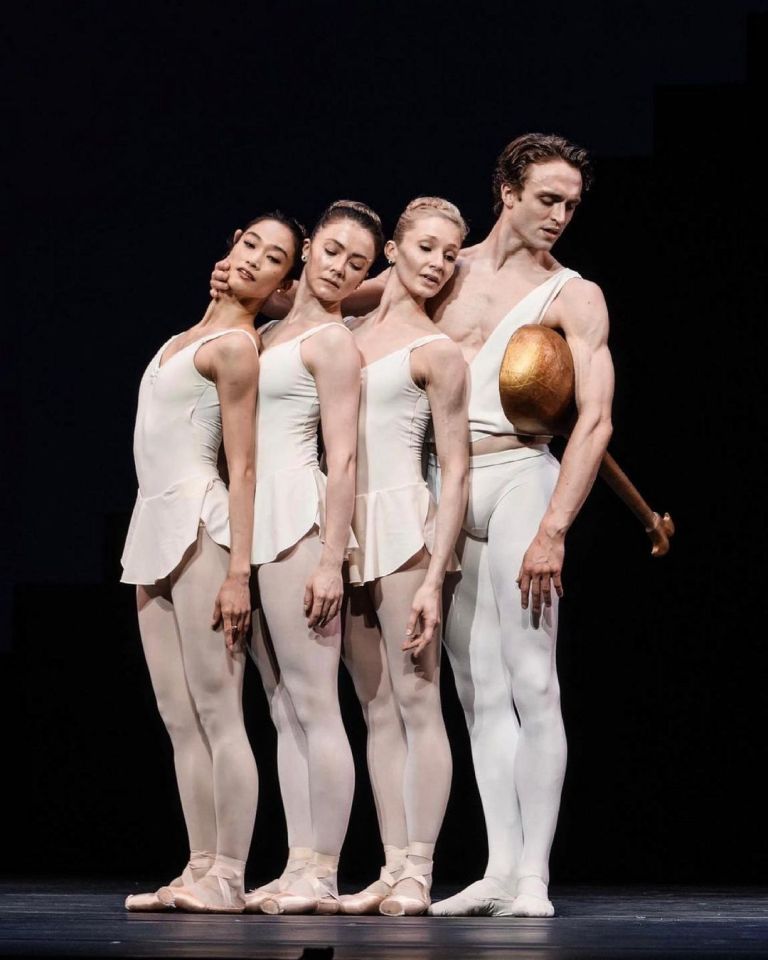

Featured image: Scene from Stanton Welch’s Divergence. Still from And we danced.