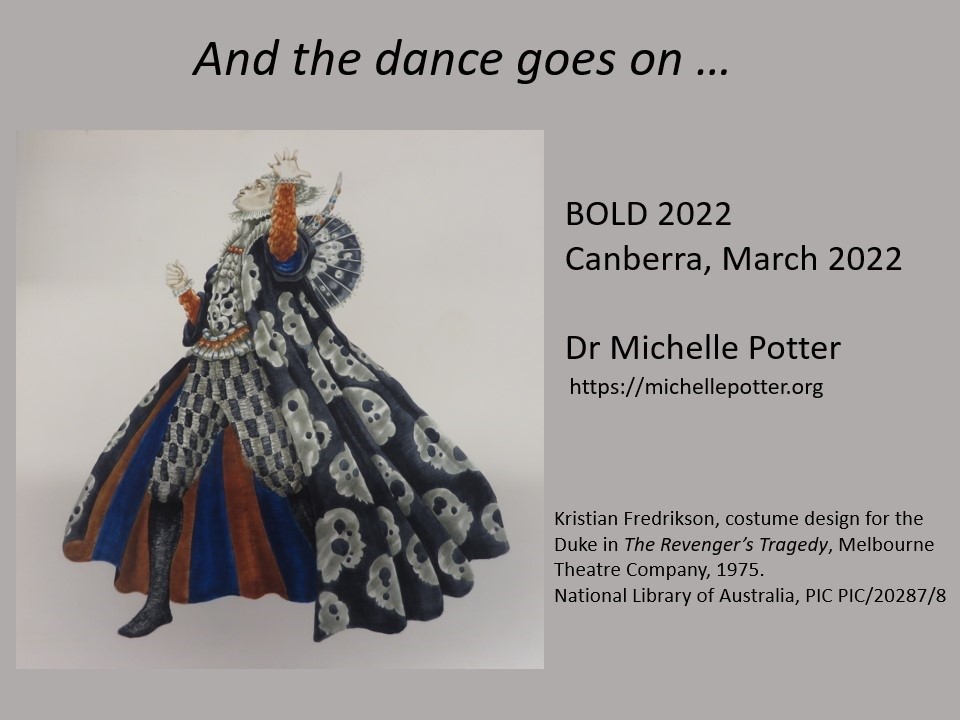

The paper below was meant to be given as a talk as part of the 2024 Russell Kerr Lecture series, which took place in Wellington on 25 February 2024. I had a misadventure with the plane that took me to Wellington (which ended up in Auckland) and in the end did not get to Wellington to deliver the talk in person. Here is a slightly altered version of what I planned to say.

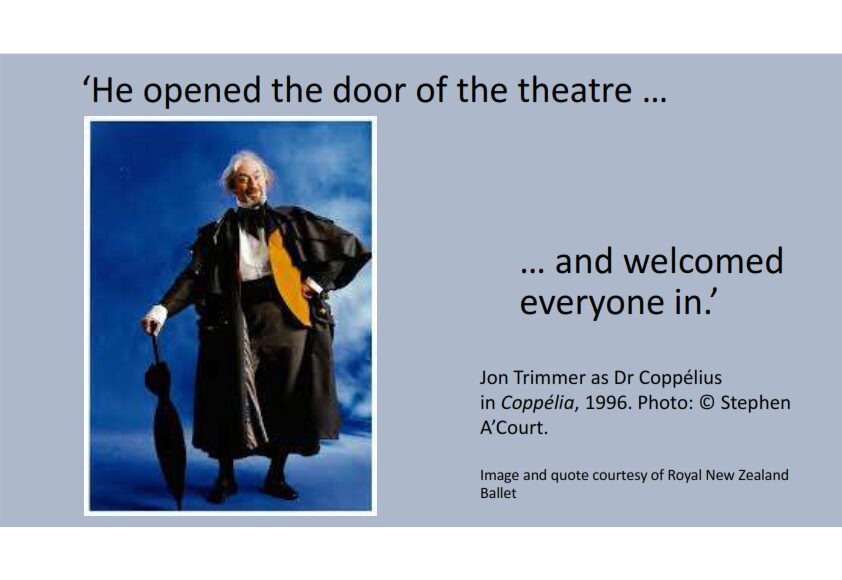

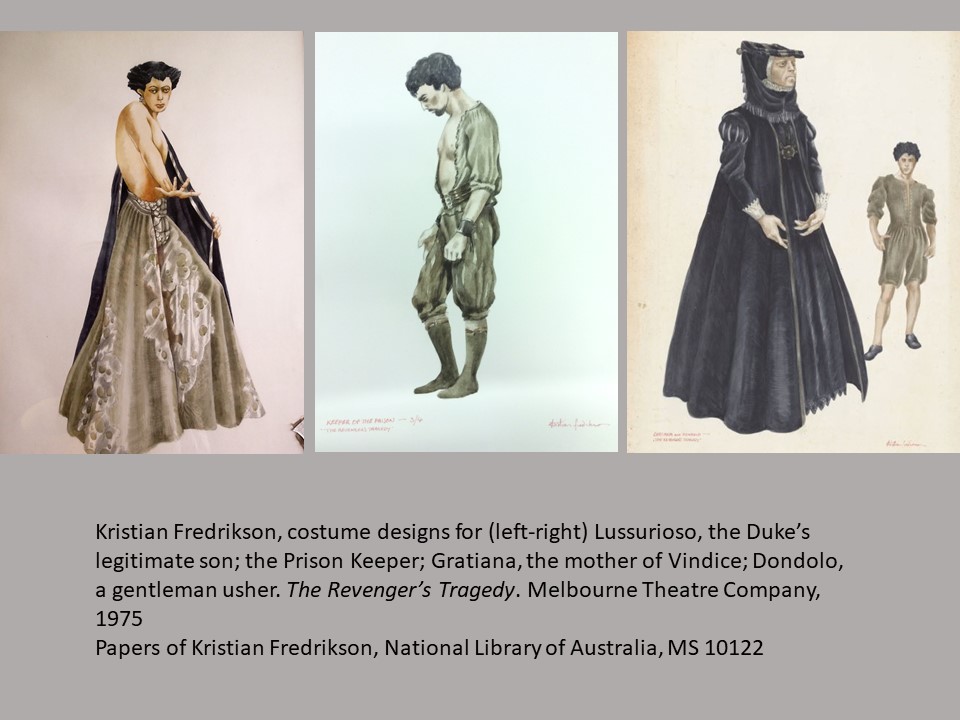

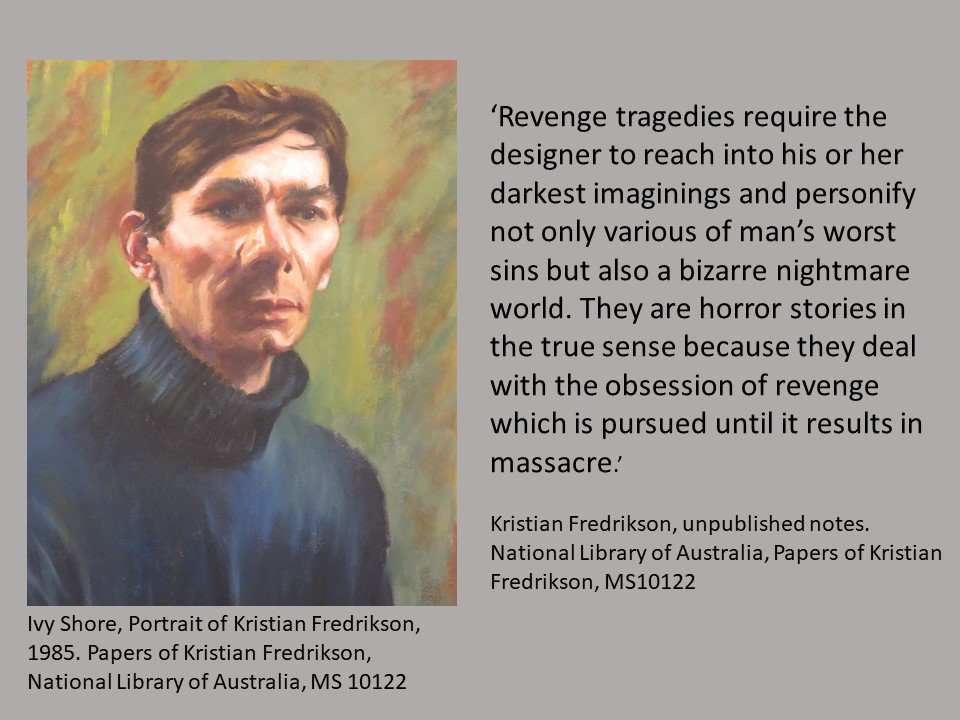

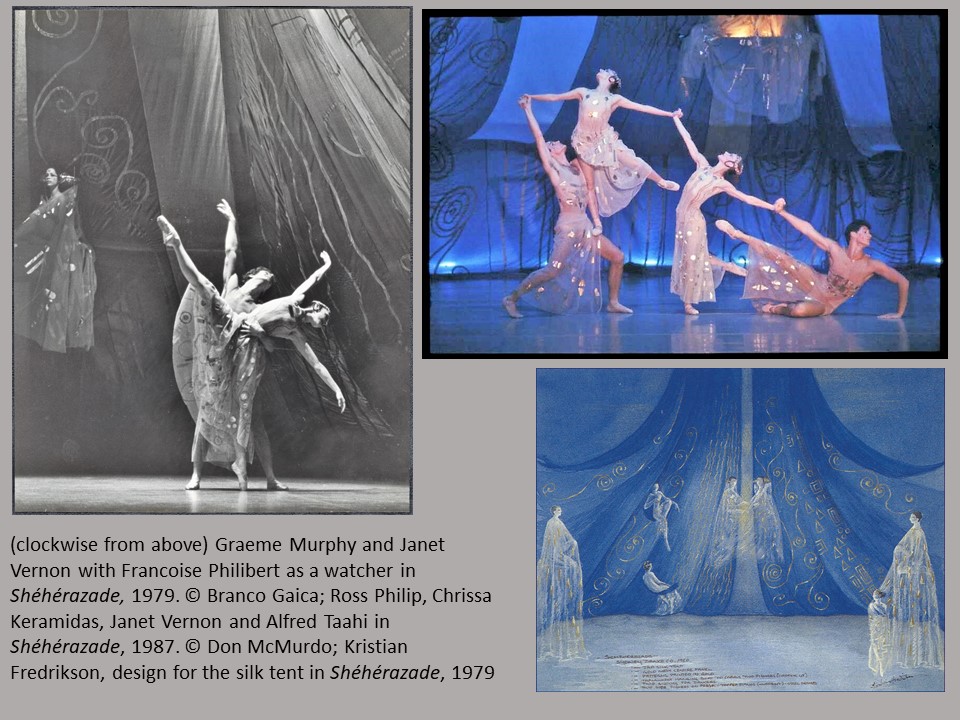

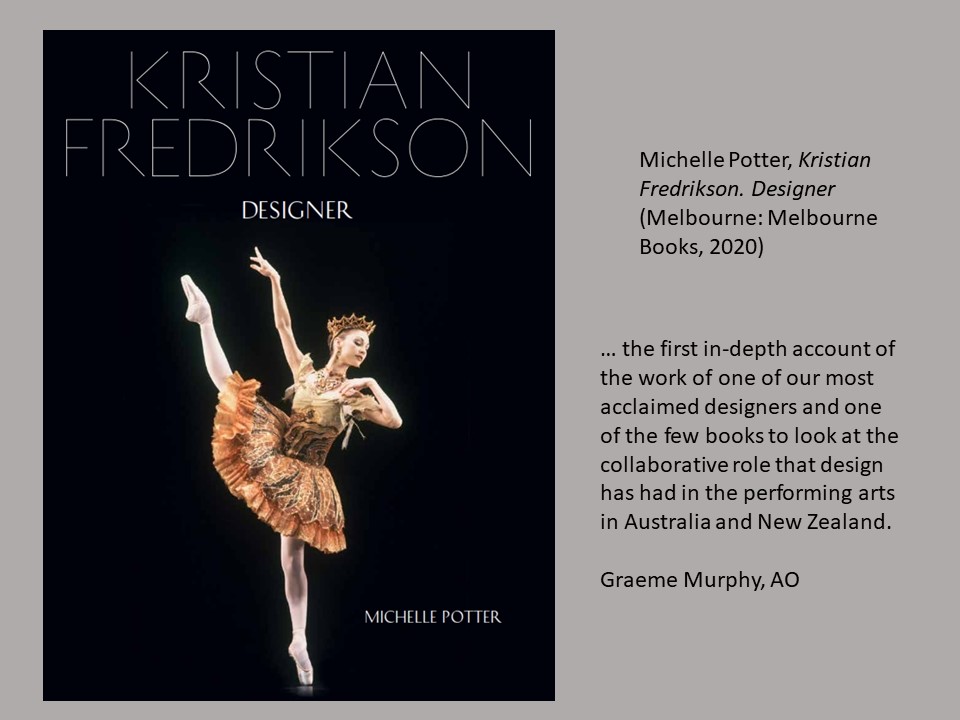

Unlike many of you here I was not a close friend of, or fellow performer with Jon Trimmer. My connection came as a result of a book I was researching about designer Kristian Fredrikson, who was a New Zealander by birth and who designed a number of works for Royal New Zealand Ballet and other New Zealand-based companies. Kristian, of course, came into contact with Jonty over and over. I first met Jonty in 2018 and spent a remarkable hour or so drinking coffee and listening to his recollections of Kristian. (And I should add here that I am calling him Jonty because he said I could when we met.)

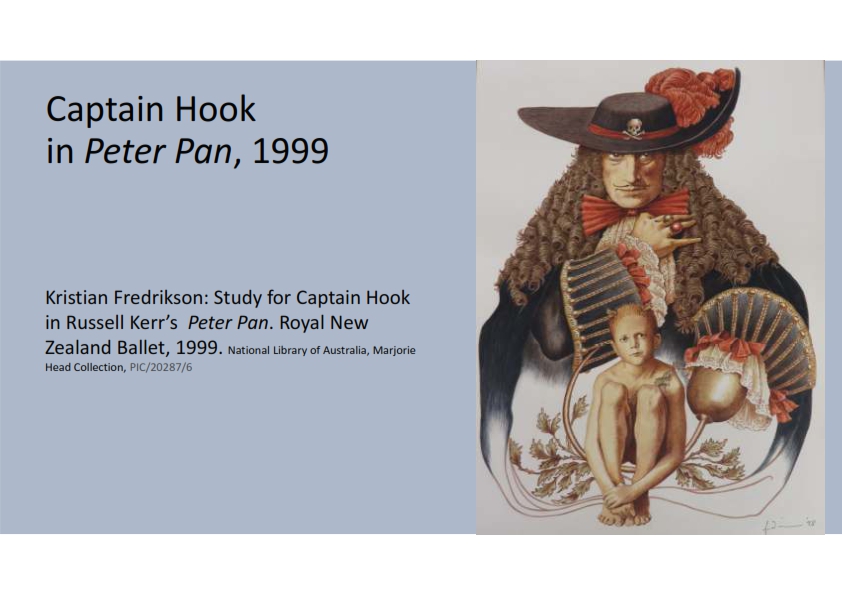

My talk today will focus on a few of the productions that Kristian designed and in which Jonty appeared. Given the short amount of time I have, it will only be a few I’m afraid. First up is Peter Pan, a work choreographed by none other than Russell Kerr. It premiered in 1999 and Jonty had the role of Captain Hook. The image below is a special study made by Kristian for Marjorie Head. Marjorie was an admired Australian milliner and worked closely with Kristian for many, many years. He made a number of special designs for her as gifts for various occasions and six of them are now in the collection of the National Library in Canberra. What you see is one of them.

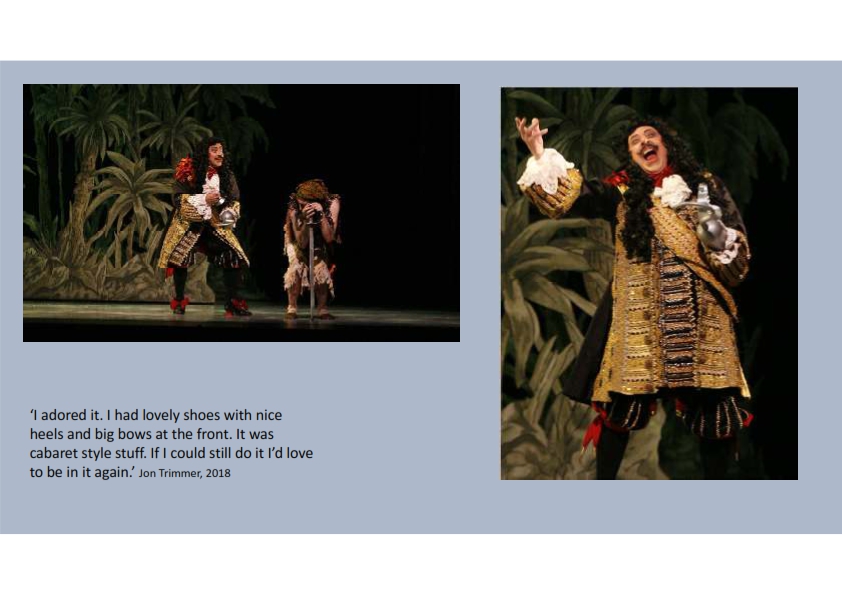

Below are two action shots from a performance of Peter Pan. Jonty loved this role and during our conversation said the words you see on the left hand side of the image, ‘I adored it. I had lovely shoes with nice heels and big bows at the front. It was cabaret style stuff. If I could still do it I’d love to be in it again.’ (Jon Trimmer, 2018)

But what is clear in these two photographs is how strongly he entered into a role. You can see it in his body, whether he is leaning forward or throwing his arms upwards. Each expresses a different emotion through his body and, of course, in his facial expression.

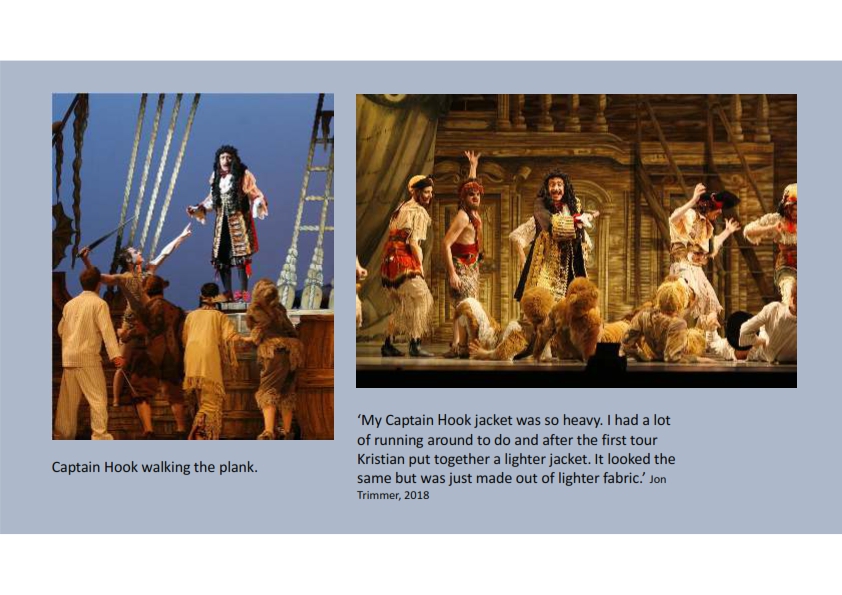

Below are two more performance shots from Peter Pan and the same may be said of them. The slightly concerned look on his face on the left-hand image contrasts with the pirately involvement we see in the right-hand image. Oh, those eyes! And that mouth! You can read what Jonty said of his costume on the slide or here, ‘My Captain Hook jacket was so heavy. I had a lot of running around to do and after the first tour Kristian put together a lighter jacket. It looked the same but was just made out of lighter fabric.’ (Jon Trimmer, 2018)

***************************************

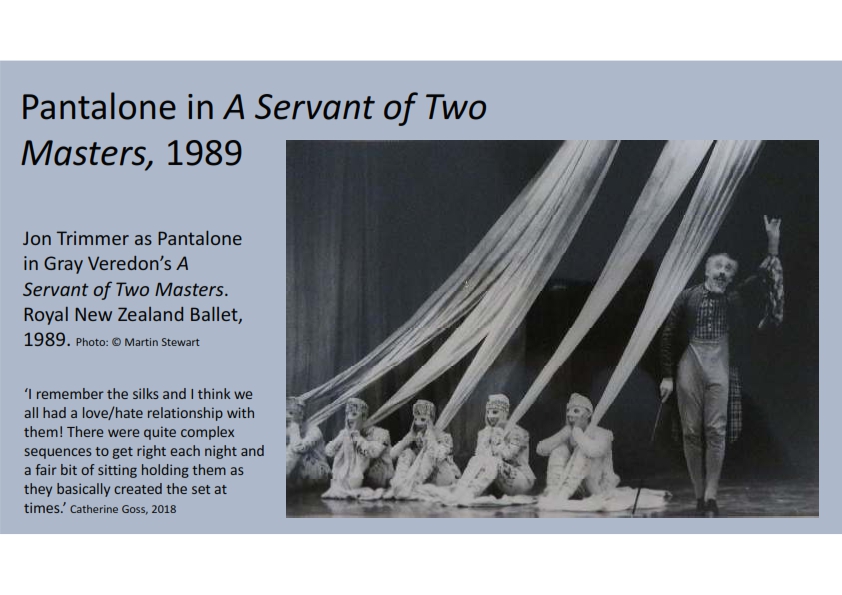

I’m moving on now to A Servant of Two Masters, a ballet choreographed by Gray Veredon based on a play of the same name by 18th century Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni.

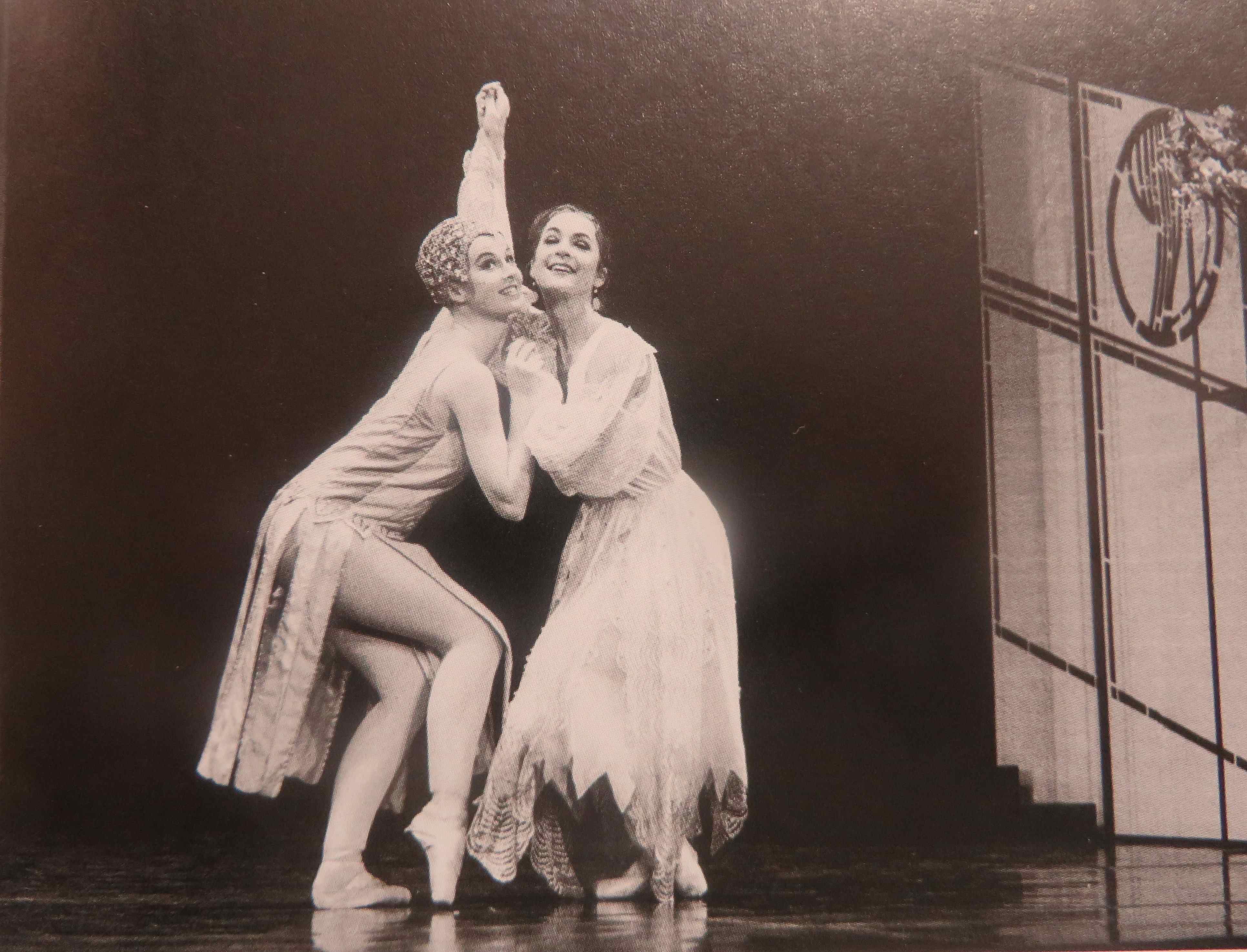

Jonty, whom you see on the right of the image, played the rich merchant Pantalone. This particular slide shows something of the set design and I found researching the set design quite interesting. No time here to go into it, other than to present what Cathy Goss, who danced in various roles in the show, had to say, ‘I remember the silks and I think we all had a love/hate relationship with them! There were quite complex sequences to get right each night and a fair bit of sitting holding them as they basically created the set at times.’ (Catherine Goss, 2018)

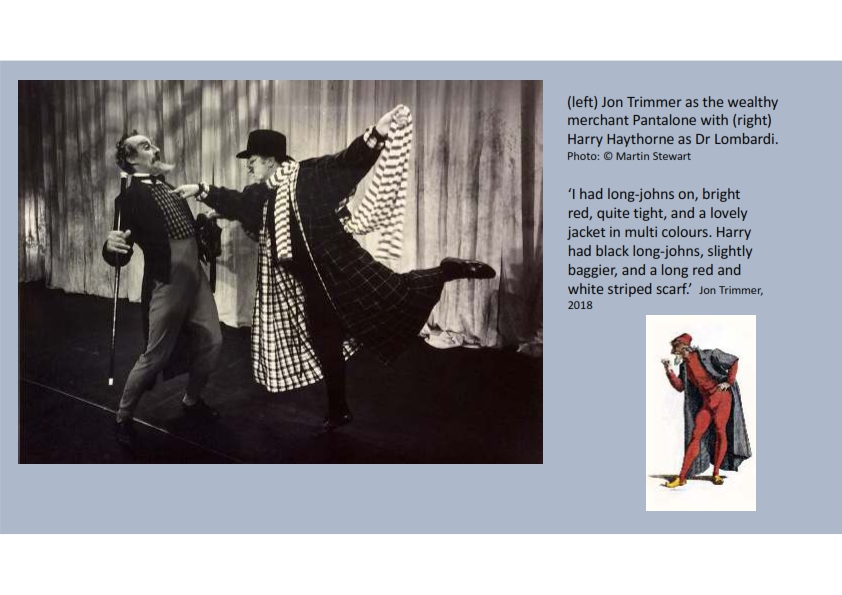

And above we see Jonty with Harry Haythorne as Dr Lombardi engaging in a somewhat dramatic moment. And notice the rather taken aback look on Jonty’s face and his curved body as he attempts to manage the somewhat dominant Lombardi. You can read what Jonty says about the costume in the text on the screen, and here, ‘I had long-johns on, bright red, quite tight, and a lovely jacket in multi colours. Harry had black long-johns, slightly baggier, and a long red and white striped scarf.’ (Jon Trimmer, 2018).

And just as an aside, I found on Wikipedia the small image at the corner of the slide. The image is from Frenchman Maurice Sand and shows Pantalone as he appeared as an Italian commedia dell arte figure. So, the red that Jonty talks about is clearly looking back to the original Pantalone.

*****************************************

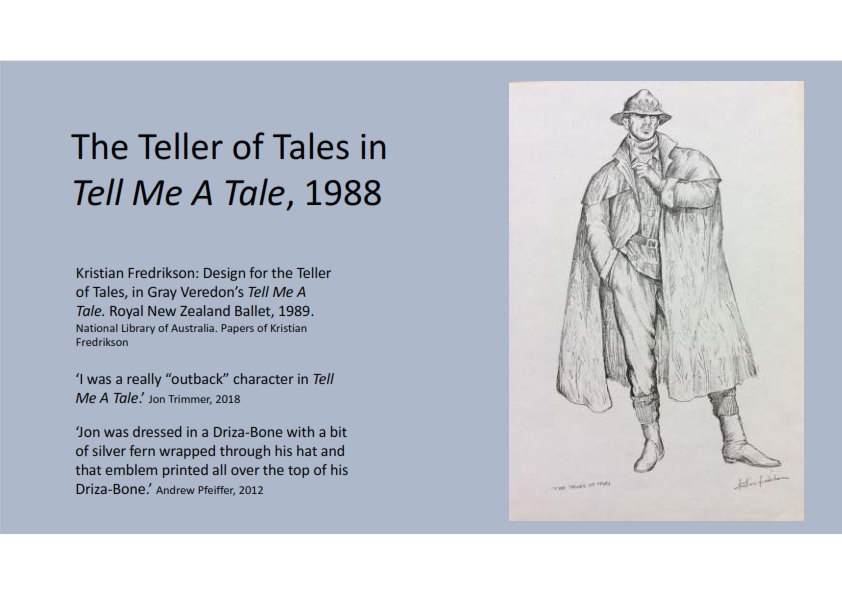

So, I’m moving on now to Tell me a Tale, Gray Veredon’s work of 1989 in which Jonty played the Teller of Tales.

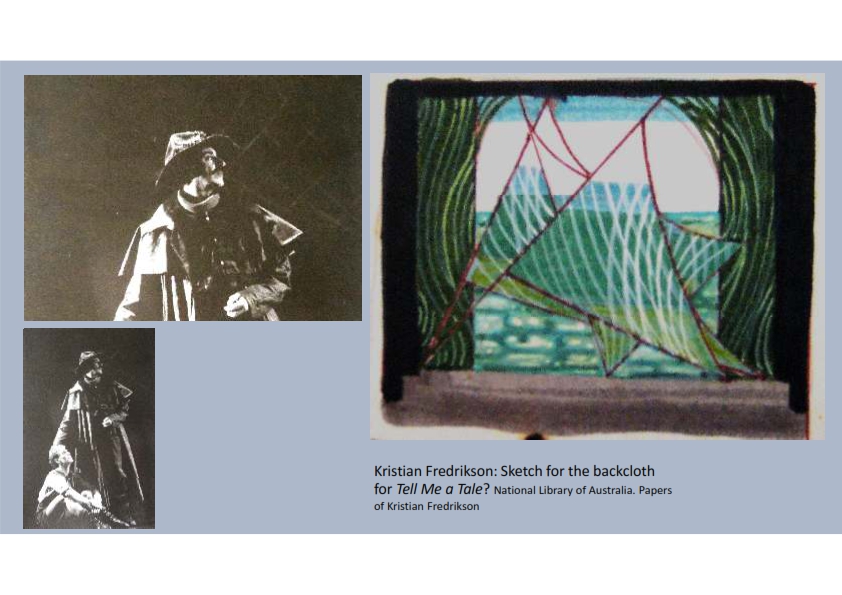

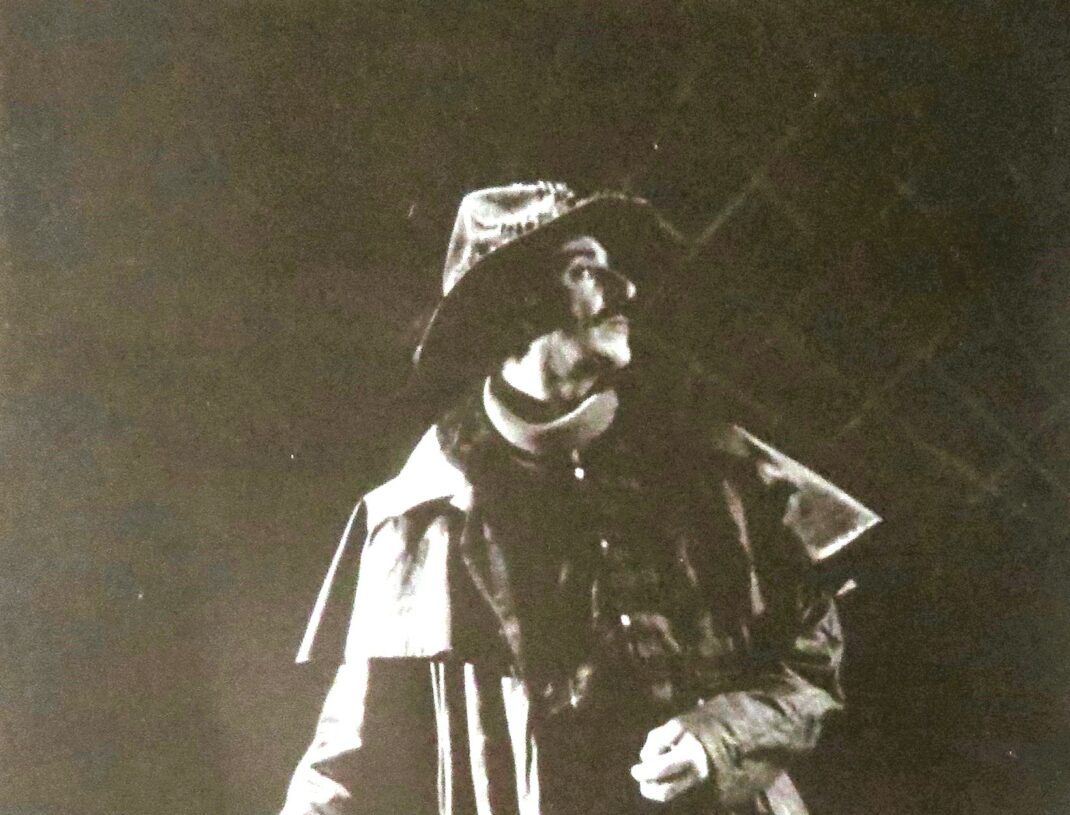

I was fascinated when I discovered the design you see on the screen – a very Australian coat, a Driza-Bone to give it its name, and Jonty refers the Teller of Tales as ‘A really outback character.’ I’m not sure if outback is also a New Zealand expression but it is very Australian referring to the land beyond the cities and the regional town areas. But if I had looked closely at the design, I would have perhaps noticed that there was a decorative element on the hat. Andrew Pfeiffer mentioned it in a talk I had with him in 2012. He said, ‘Jon was dressed in a Driza-Bone with a bit of silver fern wrapped through his hat and that emblem printed all over the top of his Driza-Bone.’ (Andrew Pfeiffer, 2012)

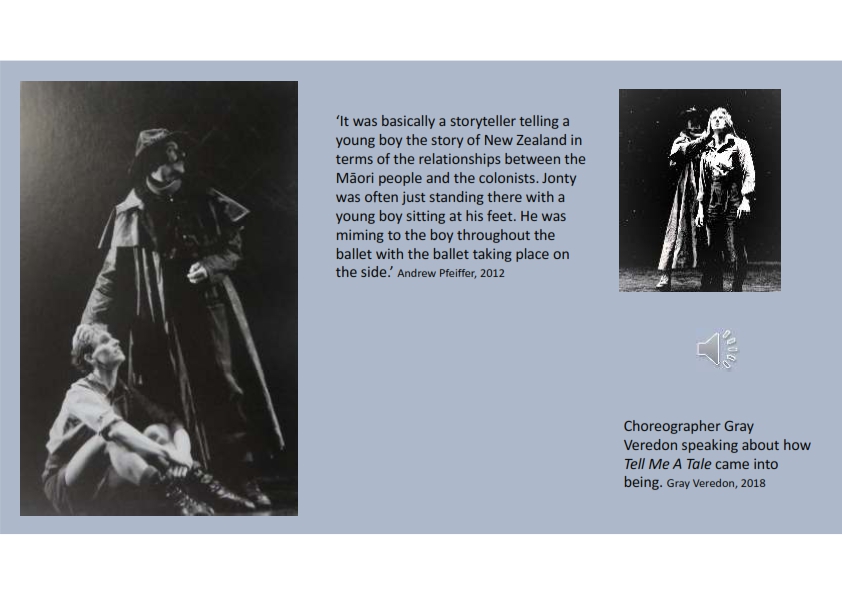

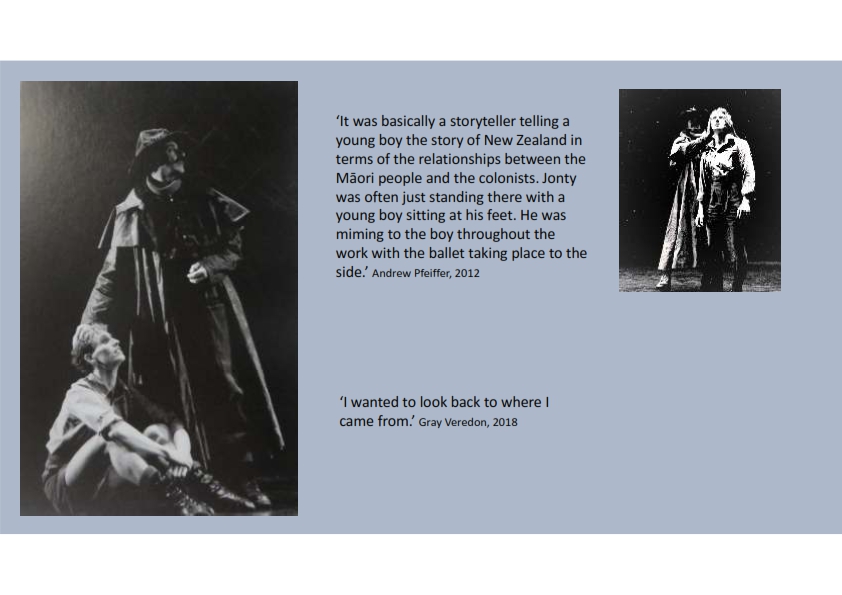

Andrew also summarised the story in a few words saying, ‘It was basically a storyteller telling a young boy the story of New Zealand in terms of the relationships between the Māori people and the colonists. Jonty was often just standing there with a young boy sitting at his feet. He was miming to the boy throughout the ballet with the ballet taking place on the side.’ (Andrew Pfeiffer, 2012)

And Gray tells the story of how it came to be called Tell Me a Tale.

I should add though that Gray starts by saying ‘Living there … ‘. ‘There’ refers to Katikati where he grew up.

Andrew Pfeiffer also helped me with something else, although I didn’t realise it until I was preparing this talk and I went back to the recording I had of our conversation in 2012. During my research I found a design in the National Library that was not identified. You can see it on the right of the screen. It was located in a box close to the costume designs for Tell Me a Tale and I wondered if it was a set design. In our interview, Andrew mentioned that Jonty was standing in front of some sails. So, with apologies to the photographer, I made some alterations to the image on the slide above – exposure, colour etc – and there they were, the sails. They are hard to see with the image transferred to this website but you can just make them out on the image below in the top right-hand corner.

But going back after that slight diversion, I think the main image on this slide shows Jonty again using all his body as he leans back and looks ahead at what will unfold. Elsewhere in the interview I did with Gray he says. ‘I wanted to look back to where I came from’ and I think we can definitely see that in Jonty’s posture and expression. And we can see a similar sense of seeking and searching in Kim Broad as the young boy.

****************************************

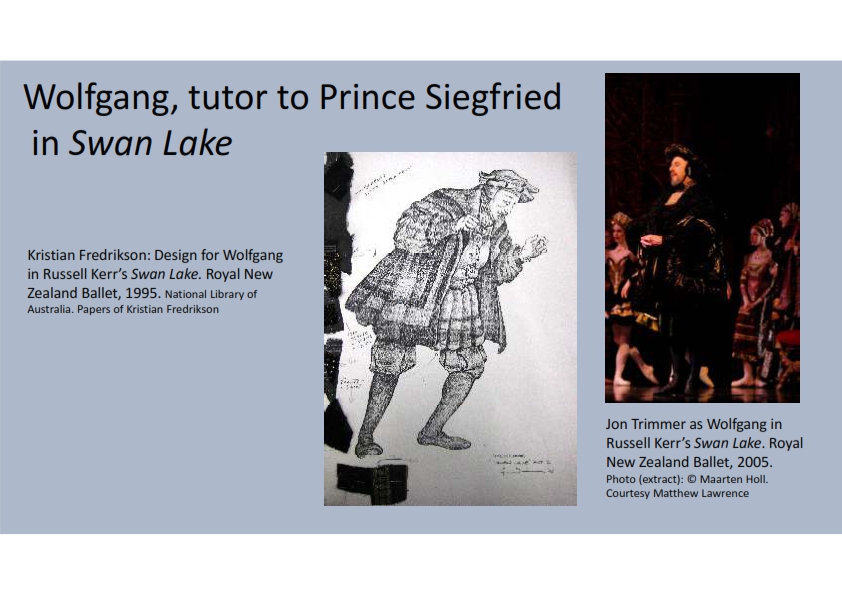

Going on now to Russell Kerr’s Swan Lake. I haven’t added a date to the heading for this slide as the work has been revived on a number of occasions. The premiere occurred in 1996 but the image I have of Jonty, as Wolfgang the tutor to Siegfried, comes from a performance in 2005. In the centre of the slide is Kristian Fredrikson’s design for Wolfgang’s costume.

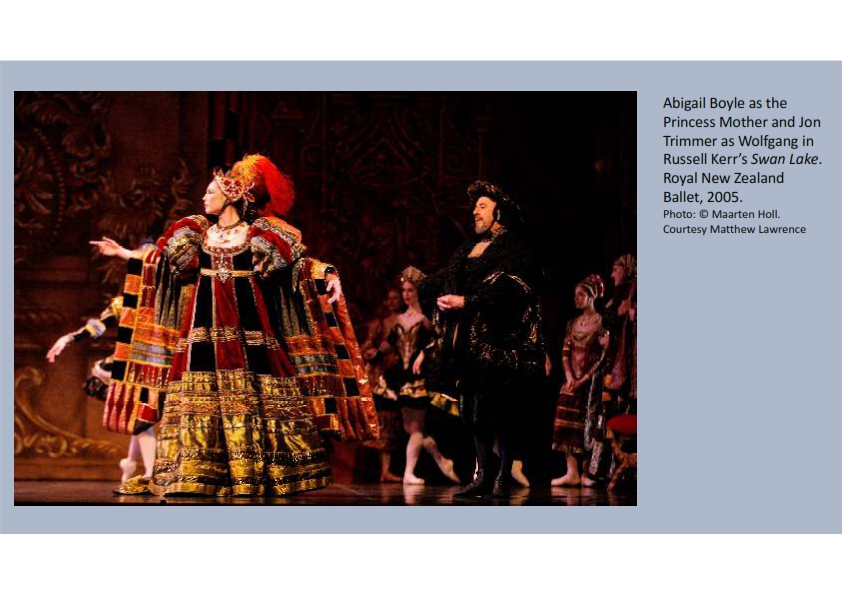

And below is the full image from which the figure of Jonty in the slide above has been extracted. You can’t help but be taken aback somewhat by the magnificence of the costume for the Princess Mother of course but I love this photo of Jonty because he is the tutor, she is the Princess Mother and, while he is dressed to kill, I think you can see in his downcast eyes, his carefully folded arms and hands and his very erect posture that he knows his place in the scheme of things, and in the society in which ballet takes place.

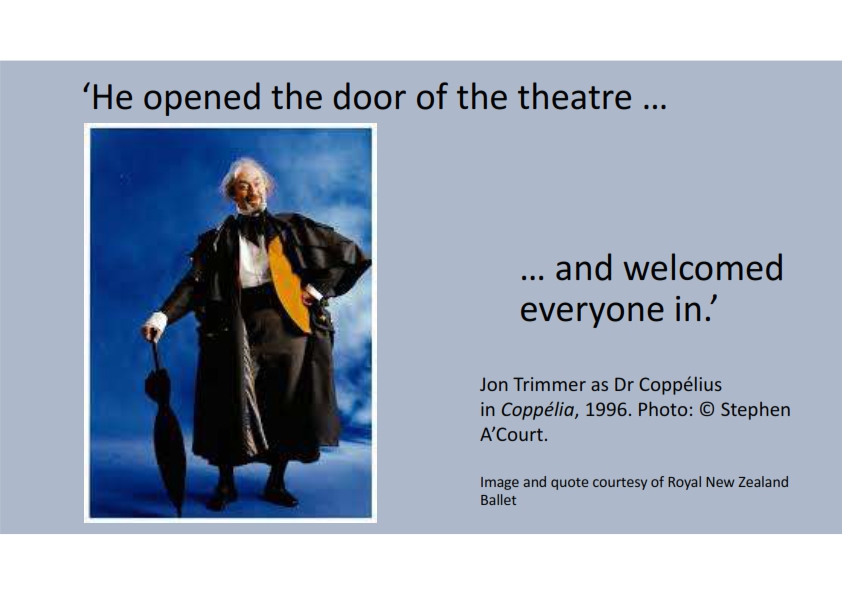

That is all I have time for so I am back now with the first image I showed. What I set out to suggest in this talk is that Jonty did open the door for us and he kept us there with the way he performed. It was not just through his technique but also through his being able to enter into the characters he was taking on in other ways as well, through his physicality and his understanding that characterisation is enhanced by every aspect of movement.

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2024