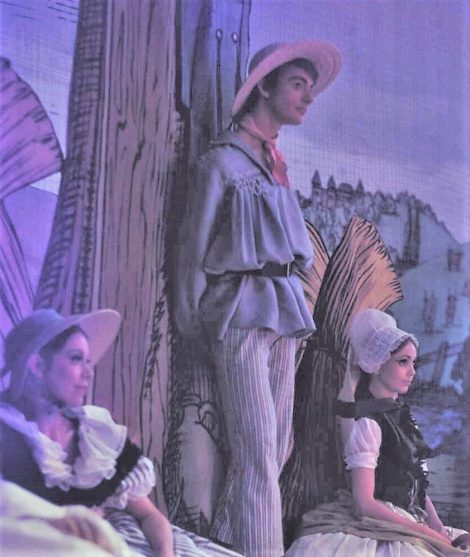

The Australian Ballet’s production of Coppélia dates back to 1979—thirty-one years ago—when it was staged by Peggy van Praggh with George Ogilvie as dramaturg. This 2020 digital screening was dedicated to Ogilvie, who died in April of this year. There is little doubt that Ogilvie’s input had a lot to do with the long-lasting success of the ballet and in fact he returned to work with the Australian Ballet for its 2016 production, which is the one we see in this online screening. Of course it can’t be denied that the visual beauty of the production, with sets and costumes by Kristian Fredrikson, added to its success. Fredrikson, who was born in Wellington, New Zealand, admitted that he designed Coppélia as a tribute to van Praagh who, back in the 1960s, gave him the opportunity to work in Australia. He regarded van Praagh as the person who nurtured his early career. It was indeed a lovely tribute from Fredrikson since Coppélia was a work in which van Praagh herself had shone during her own dancing career.

The dancing in many of the productions of Coppélia I have seen has often been of a rather mixed quality. But not this time. Led by Ako Kondo as Swanilda, Chengwu Guo as Franz and Andrew Killian as Dr Coppélius, with a stunning supporting cast, there was little to complain about, and everything to admire as far as performance goes.

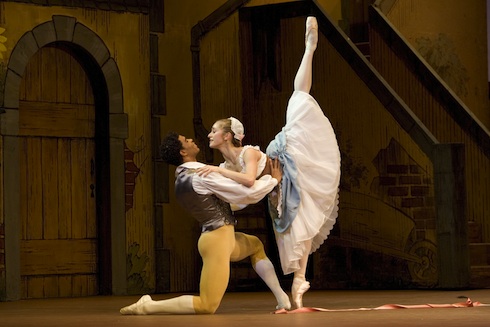

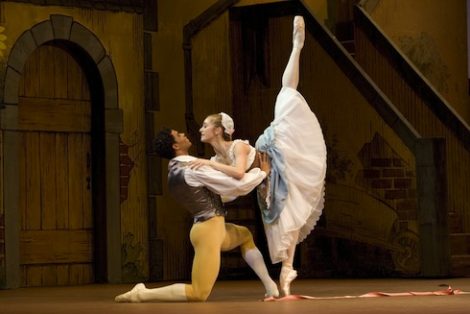

Kondo shone technically and in her acting, as did Guo. I especially loved the moments in Act I where the two of them stood in line to greet the official party arriving in the village square with Kondo declining, in no uncertain terms, to hold Guo’s hand (he had been paying too much attention to the doll on Dr Coppélius’ balcony). I also admired the grand pas de deux in Act III, which unfolded beautifully and was technically spectacular.

Andrew Killian was an interesting Dr Coppélius, not too over the top but very believable as an eccentric man totally absorbed in perfecting his magical powers. There was a lovely, calm rendition of the Prayer solo in Act III from Robyn Hendricks. And the corps de ballet deserves special mention for the vibrantly performed character dances in Act I. The Mazurka had its leading couple, but Guo joined in with a solo that added some spectacular moments in true principal artist fashion—exceptionally controlled turns, magnificent jumps and a truly beautiful showman-style use of head, chest and arms

As has been the case with pretty much every streamed production I have watched recently, it was great to see the occasional close-up shot of an individual dancer to give us a view of facial expressions and, of course, to give insight into the details of costumes.

My review of a 2016 performance, which I saw in Sydney with a quite different cast is at this link.

Michelle Potter, 20 July 2020

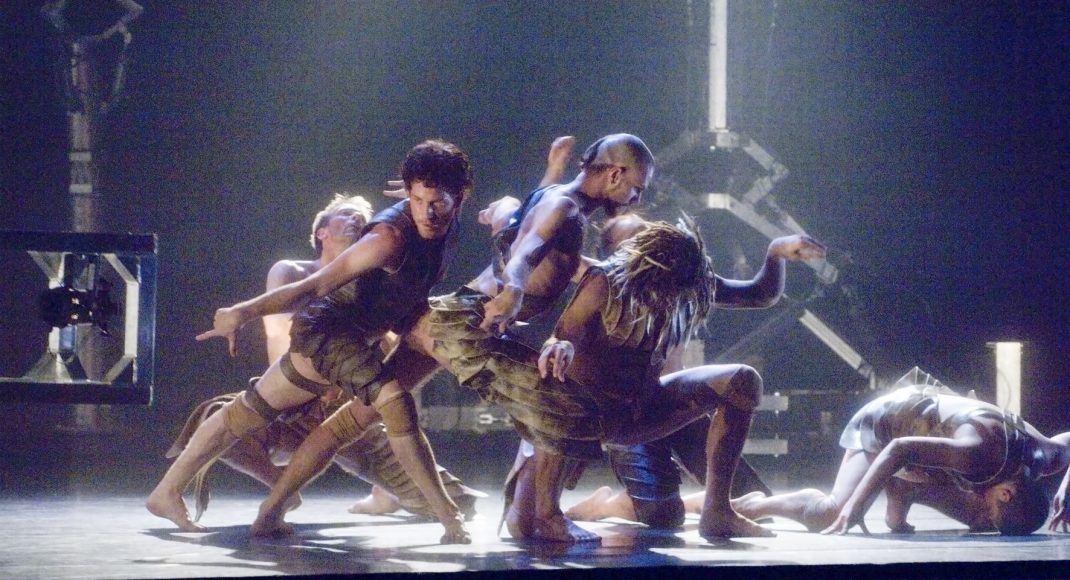

Featured image: Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo in the grand pas de deux in Coppélia Act III. The Australian Ballet, 2016. Photo: © Jeff Busby

Postscript: It was extremely annoying that the cast sheet that was available on the Australian Ballet’s website, supposedly to give us information about the cast, was not the correct one. It was dated the evening performance in Sydney of 16 December 2016 but the cast was entirely different from the one we saw, who also, apparently, performed on 16 December. Perhaps there was a matinee performance on 16 December? But at least there were credits at the end of the film, which helped.